Contents

ToggleA woman walks into a patent office in 1932, carrying a contraption made from soap bars, paper clips, and buttons. The male engineers laugh at her.

She’s told her invention is mechanically impossible. Three hours later, she walks out with a patent application that will change how every office in America operates.

The woman is Beulah Louise Henry, and by the time she dies, she’ll hold more patents than any other woman in history—49 official patents and over 110 inventions that touch your life right now, today, in ways you never imagined.

The Girl Who Couldn’t Stop Inventing

Beulah Louise Henry was born on September 28, 1887, in Raleigh, North Carolina, with revolution already coded in her DNA. Her great-grandfather was Patrick Henry, the firebrand who declared “Give me liberty or give me death.”

Her grandfather, W.W. Holden, was a controversial North Carolina governor during Reconstruction who fought the Ku Klux Klan and got impeached for it. She descended directly from President Benjamin Harrison.

But young Beulah wasn’t interested in political revolution. She was obsessed with mechanical revolution.

At age nine, while other Southern girls practiced piano scales and perfected their needlework, Beulah filled notebook after notebook with mechanical drawings. She drove every adult in her life absolutely crazy by constantly pointing out everything wrong with the objects around her. A door handle that stuck? She’d sketch three different solutions. A parasol that flipped inside out in the wind? She’d design a reinforcement system. Her favorite childhood game involved identifying problems and creating fixes.

Her parents, Walter and Beulah Sr., recognized their daughter’s unusual mind but had no idea what to do with it. This was 1890s North Carolina. Girls from good families didn’t become inventors. They became wives. But Beulah’s brain simply wouldn’t cooperate with social expectations.

Her first real invention concept emerged during childhood: a mechanical hat tipper that would automatically lift a man’s hat when he greeted someone. Adults dismissed it as childish fantasy.

But the concept revealed something profound—this nine-year-old already understood automation, mechanical advantage, and the possibility of machines handling social conventions.

The Henrys made a choice that would change industrial history. Instead of crushing their daughter’s mechanical obsessions, they quietly supported them. They bought her drawing supplies. They let her take apart household objects. They sent her to Elizabeth College in Charlotte, one of the few Southern institutions that offered women any kind of technical education.

College Years and the First Patent

Elizabeth College wasn’t MIT, but it gave Henry something crucial: space to experiment without constant judgment. Between 1909 and 1912, she studied there, though “studied” doesn’t quite capture what she was doing. While attending required classes in literature and languages, Henry was secretly developing her first major invention in her dorm room.

The vacuum ice cream freezer sounds mundane today, but in 1912, it was revolutionary. Traditional ice cream makers required massive amounts of ice and rock salt. They were messy, inefficient, and exhausting to operate. Making ice cream at home was a luxury only wealthy families with servants could manage. Henry saw this as a solvable problem.

Her design used vacuum pressure to reduce the freezing point, requiring minimal ice and eliminating the need for rock salt entirely. The mechanism was elegant—simple enough for a child to operate but sophisticated enough to produce consistent results. She filed for a patent in 1912, before even graduating from college. Patent number 1,037,762 was granted, making her one of the youngest women in America to hold a patent.

But here’s where Henry’s story takes an unexpected turn. Most inventors would have tried to manufacture and sell their invention. Henry had bigger plans. She saw the ice cream freezer not as an endpoint but as proof of concept. She could identify problems, design solutions, and navigate the patent system. The real question was: what else could she invent?

New York City: Living in Hotels and Shocking Everyone

After graduating in 1912, Henry made a decision that scandalized Southern society. She moved to New York City. Not with a husband. Not to find a husband. She moved there with her mother as a chaperone, but make no mistake—this was Beulah’s show. She was going to New York to become a professional inventor.

She set up shop in Manhattan hotels. Not an apartment. Not a house. Hotels. This wasn’t because of poverty since Henry had family money. This was strategy. Living in hotels meant she could relocate instantly when business demanded. She didn’t have to manage a household. She could focus entirely on inventing. For the next 60 years, Beulah Louise Henry would live out of hotel rooms, conducting business meetings in lobbies and turning hotel suites into makeshift laboratories.

From these hotel rooms, she launched two companies: the Henry Umbrella and Parasol Company, and later, the B.L. Henry Company. She hired draftsmen, model makers, and patent lawyers—all men, all initially skeptical of taking orders from a woman. But Henry had an advantage: she could pay them, and her ideas actually worked.

The Inventions That Changed Everything

The Snap-On Parasol Revolution

In 1924, Henry received a patent for something that sounds ridiculous today but was genius for its time: an umbrella with snap-on fabric covers. Women in the 1920s coordinated their parasols with their outfits. This meant owning multiple expensive parasols or looking unfashionable. Henry’s design let women buy one parasol frame and multiple fabric covers that could snap on and off in seconds.

The invention wasn’t just about fashion. It revealed Henry’s understanding of modular design—a concept that wouldn’t become widespread in manufacturing for another 30 years. She saw that separating form from function could create new markets and reduce costs. Every smartphone case you’ve ever owned owes something to Henry’s snap-on parasol.

Revolutionizing Childhood: The Inflatable Doll

Henry’s next major breakthrough came in 1927 with inflatable doll technology. Traditional dolls were stuffed with sawdust, rags, or other heavy materials. They were expensive to ship, uncomfortable to hold, and impossible to clean. Poor families could rarely afford quality dolls for their children.

Henry developed a system using rubber tubing that could be inflated to create lightweight, affordable dolls. But here’s the brilliant part: she didn’t just make the dolls lighter. She engineered the inflation system to create more realistic body proportions and movements. The dolls could be squeezed and would bounce back. They could be washed. They could be deflated for storage or travel.

Toy manufacturers initially resisted. They claimed mothers wouldn’t trust inflatable toys. Henry responded by creating “Miss Illusion,” a doll with color-changing eyes that could open and close naturally. The mechanism was so sophisticated that engineers couldn’t figure out how she’d done it with 1935 technology. The doll became a sensation, and suddenly every toy company wanted Henry’s designs.

The Double Chain Stitch Sewing Machine: Her Masterpiece

Henry’s most important invention came in 1940: the bobbin-free sewing machine. To understand why this matters, you need to understand what sewing was like before Henry fixed it.

Traditional sewing machines used bobbins—small spools that supplied the bottom thread for stitching. Bobbins were the worst part of sewing. They ran out of thread constantly, requiring operators to stop and rewind them. The thread tangled and broke. Tension problems ruined entire garments. Professional seamstresses spent almost as much time fighting with bobbins as actually sewing.

Henry eliminated the bobbin entirely.

Her double chain stitch design fed thread directly from regular spools using a mechanism that created stronger stitches while doubling production speed. Seamstresses could use finer threads without sacrificing strength. The machine never needed to stop for bobbin changes. Beginners could achieve professional results without mastering complex tension adjustments.

The impact was immediate and massive. Garment factories doubled their output overnight. Home sewers could complete projects in half the time. The cost of clothing plummeted while quality improved. Working-class families could suddenly afford fashionable clothes. The entire ready-to-wear industry—everything you’re wearing right now—exists because Henry made mass production of quality garments economically viable.

The Protograph: Killing Carbon Paper

In 1932, Henry tackled one of the biggest problems in American offices: document duplication. Before photocopiers, making copies meant using carbon paper—messy, unreliable sheets that produced terrible copies and ruined typewriter ribbons. Secretaries spent hours managing carbon paper, and the copies degraded quickly.

Henry’s Protograph attached to any standard typewriter and mechanically produced up to four identical copies without carbon paper. The copies were clean, permanent, and identical to the original. The device was purely mechanical—no electricity required—and could be installed in minutes.

HerWiki is built and maintained by the support of amazing readers like you. If this story inspired you, join the cause and help us make HerWiki bigger and better.

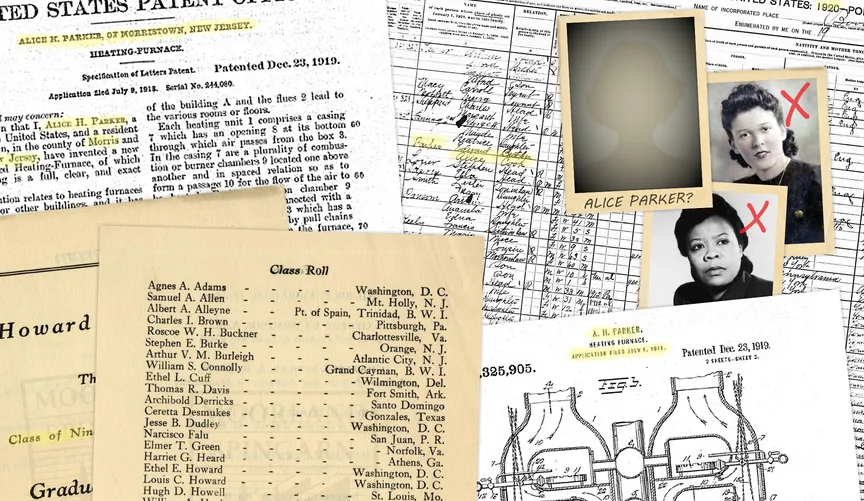

When Henry brought her prototype to the patent office, engineers said it was impossible. The mechanism she described violated their understanding of typewriter mechanics. Henry pulled out a prototype made from soap, paper clips, and rubber bands. She demonstrated it on their own typewriter. The patent was approved that day.

Within two years, thousands of offices had installed Protographs. Government agencies used them for record-keeping. Law firms used them for contracts. The technology bridged the gap between manual copying and modern photocopying, keeping American bureaucracy functional for three crucial decades.

The Woman Who Wouldn’t Marry

Beulah Louise Henry never married, and this wasn’t an accident or tragedy—it was strategy. In the early 1900s, marriage meant legal death for a woman inventor. Husbands automatically gained control over wives’ patents, income, and business decisions. The few married women inventors of the era often found their husbands claiming credit for their work or selling their patents without permission.

Henry chose her inventions over convention. She belonged to scientific societies. She attended engineering conferences where she was often the only woman in rooms of hundreds of men. She negotiated with manufacturers who initially refused to believe a woman could understand her own inventions.

Living in hotels gave her a respectable address without domestic obligations. She could work eighteen-hour days without anyone complaining about missed dinners. She could travel instantly for business without arranging household management. The hotel staff handled the cooking, cleaning, and maintenance that would have consumed her time in a traditional home.

This lifestyle was radical. Newspapers called her “Lady Edison” but always mentioned her unmarried status, as if it were a character flaw. Society columns speculated about why such an accomplished woman couldn’t find a husband. They completely missed the point: Henry didn’t want a husband. She wanted patents.

Fighting Sexism With Soap and Paper Clips

Throughout her career, Henry faced discrimination that would have broken most people. Patent clerks questioned whether she understood her own inventions. Male engineers explained to her why her working prototypes were theoretically impossible. Manufacturers put their company names on her designs without crediting her. Business publications ignored her achievements while celebrating mediocre work by male inventors.

Henry developed a unique strategy for handling sexism: overwhelming competence. When engineers said her invention wouldn’t work, she built it from household materials and demonstrated it in their offices. When manufacturers claimed her designs were too complex for production, she created simplified versions that could be assembled by untrained workers. When patent clerks doubted her authorship, she provided detailed technical drawings and mathematical proofs she’d created herself.

Her famous soap-and-paper-clip prototypes became legendary in the patent office. She’d walk in with what looked like garbage—soap bars connected with bent paper clips, rubber bands stretched between pencils, buttons serving as bearings. Then she’d demonstrate mechanisms that trained engineers hadn’t imagined. The prototypes were crude but undeniable. They worked.

She kept meticulous records of every invention, every meeting, every conversation. When companies tried to steal her designs, she had documentation. When male inventors claimed credit for her work, she had dated sketches proving priority. She learned to get everything in writing, to file patents immediately, and to maintain ownership even when licensing designs to manufacturers.

The Hidden Revolution in Women’s Daily Life

Many of Henry’s inventions specifically addressed problems women faced in the 1920s and 1930s. Her hair curler design eliminated heat damage while reducing styling time. Her vanity case integrated multiple cosmetics into a durable, portable container that could survive purse jostling. Her rubber sponge soap holder kept bar soap sanitary and dry—crucial when bar soap was the only option for feminine hygiene.

These weren’t frivolous inventions. They were tools of liberation. Women entering the workforce in the 1920s needed portable cosmetics for touch-ups during long work days. They needed hair styling tools that worked quickly before morning shifts. They needed hygiene products that could travel from home to office. Henry understood that women’s economic independence required practical solutions to daily problems men never considered.

Her “Dolly Dips” soap-filled sponges for children seem simple but solved a real problem: getting children to wash properly without constant supervision. Mothers working in factories during World War II couldn’t hover over their children during bath time. Henry’s invention made hygiene fun and automatic, freeing mothers for war work that helped win the conflict.

Working With the Big Boys

By 1939, Henry’s reputation had grown enough that major corporations sought her out. Nicholas Machine Works hired her as an inventor—not a consultant, not an advisor, but an inventor. Her job was to create new products and improve existing ones. She was one of the first women in American history to hold such a position at a major manufacturing company.

She also worked with Mergenthaler Linotype Company, developing improvements to their typesetting machines that newspapers depended on. International Doll Company contracted her to revolutionize their entire product line. These weren’t token positions. Henry generated significant revenue for these companies through innovations that improved efficiency and opened new markets.

But even with this success, Henry faced constant battles for recognition. Companies routinely put their names on her inventions without crediting her. Press releases described breakthrough products without mentioning their female inventor. When forced to acknowledge her contributions, companies often called her a “consultant” or “advisor” rather than admitting a woman had created their most profitable innovations.

The Philosophy of Practical Innovation

Henry developed a unique philosophy about invention that differed radically from the academic approach. She believed that the best innovations came from identifying genuine problems rather than showing off technical capabilities. Every invention should make someone’s life easier, faster, or better. Complexity for its own sake was failure.

“If necessity is the mother of invention,” she once said, “then resourcefulness is the father.” This wasn’t just a clever quote. It was her methodology. She started with necessity—real problems real people faced. Then she applied resourcefulness—finding unconventional solutions using available materials and technologies.

She also believed in what she called “democratic invention”—creating products that ordinary people could afford and use. Her bobbin-free sewing machine wasn’t for industrial giants; it was for mothers making their children’s clothes. Her inflatable dolls weren’t for wealthy collectors; they were for working-class children who deserved quality toys.

This philosophy put her at odds with the male-dominated invention establishment, which prioritized impressive engineering over practical utility. While men were inventing increasingly complex machines to demonstrate technical mastery, Henry was simplifying existing machines to make them actually useful.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

By the time Beulah Louise Henry died on February 1, 1973, she had accumulated:

- 49 U.S. patents (more than any other man or woman at that time)

- Over 110 inventions (many unpatented but manufactured)

- Contracts with dozens of major corporations

- Income streams from licensing deals that continued for decades

But the real impact can’t be measured in numbers. Every piece of clothing you own was made possible by her sewing innovations. Every document you’ve ever photocopied owes something to her reproduction technology. Every inflatable pool toy, exercise ball, or air mattress uses principles she pioneered.

The Decades of Invisibility

After Henry’s death in 1973, something strange happened: she disappeared from history. Despite holding more patents than any other woman of her era, despite revolutionizing multiple industries, despite living such an unconventional life, she vanished from textbooks, documentaries, and museum exhibits.

This wasn’t accidental. The feminist movement of the 1970s was looking for different kinds of heroes—women who fought explicitly for women’s rights, who marched and protested and demanded equality. Henry had taken a different approach. She’d simply ignored the rules and invented her way around discrimination. This didn’t fit the narrative of the time.

The invention establishment also had reasons to forget her. Admitting that a woman with no engineering training had out-invented formally educated male engineers raised uncomfortable questions. How many other women might have become inventors if given the chance? How much innovation had society lost by excluding half the population from technical fields?

For thirty years, Henry remained forgotten. Her patents gathered dust in government archives. Her inventions were attributed to the companies that manufactured them or to male engineers who’d refined them. The woman who’d changed how America dressed, played, and worked was erased from the story of American innovation.

The Modern Recognition That’s Not Enough

In 2006, the National Inventors Hall of Fame finally inducted Beulah Louise Henry—33 years after her death. The citation acknowledged her 49 patents and influence on American industry. But even this recognition felt hollow. She was inducted in a group ceremony, her achievement paragraph squeezed between male inventors who’d done far less. Museums still don’t feature her work. Textbooks might mention her in a sidebar about “women inventors” but never in the main narrative of American innovation.

This isn’t just about giving credit where it’s due. It’s about understanding how innovation actually happens. Henry proved that formal education isn’t necessary for breakthrough invention. She demonstrated that practical problems often have simple solutions that experts overlook. She showed that being an outsider—female, untrained, unconventional—could be an advantage in seeing what insiders missed.

Her collaborative approach, working with craftsmen and manufacturers to refine ideas, preceded modern team-based innovation by decades. Her focus on user experience over technical impressiveness anticipated design thinking by half a century. Her modular, adaptable products predicted customization and personalization trends that define modern consumer goods.

Why Nobody Told You About Her

The erasure of Beulah Louise Henry from history isn’t just sexism—though that’s certainly part of it. It’s also about how we tell the story of progress. We prefer lone genius narratives: Edison with his light bulb, Bell with his telephone, Ford with his assembly line. Henry’s story is messier. She improved existing technologies rather than creating entirely new categories. She solved practical problems rather than theoretical ones. She collaborated rather than commanding.

Her story also challenges comfortable assumptions about the past. We like to believe that talent inevitably rises, that genius can’t be suppressed, that the best ideas win. Henry’s success required constant fighting, strategic maneuvering, and enormous sacrifice. How many other women had similar talents but couldn’t overcome the barriers? How many innovations did we lose because their inventors wore skirts?

The patent office records suggest an answer: thousands. In Henry’s era, women filed patents at rates far below their population percentage. The few who did often filed under initials or male names to avoid discrimination. We’ll never know what problems might have been solved, what technologies might have emerged, if women like Henry had been encouraged rather than excluded.

The Revolutionary Hidden in Plain Sight

Beulah Louise Henry was a revolutionary who never marched, never protested, never made speeches about women’s rights. Her revolution was quieter but perhaps more profound. She simply refused to accept that being female meant she couldn’t invent. She ignored social conventions that said unmarried women were failures. She built businesses when women couldn’t even vote in many states.

Every time she walked into a patent office with a soap-and-paper-clip prototype, she was committing an act of rebellion. Every time she negotiated with manufacturers who didn’t believe women could understand mechanics, she was fighting for equality. Every patent she filed was a declaration that women’s ideas had value, that female perspectives could improve the world, that innovation wasn’t exclusively male territory.

She didn’t wait for permission. She didn’t ask for acceptance. She just invented, patented, and profited while society scrambled to explain how a Southern lady with no engineering degree could out-invent MIT graduates.

The Legacy Living in Your Closet

Look around your home right now. Your clothes were made on machines using principles Henry pioneered. Your children’s toys use manufacturing techniques she developed. Your office equipment incorporates technologies she invented. If you’ve ever used a photocopier, worn mass-produced clothing, or bought an inflatable product, you’ve benefited from Beulah Louise Henry’s refusal to stay in her place.

But her greatest invention might have been herself: the independent woman inventor. She created a template that shouldn’t have been able to exist in early 20th-century America. She proved it was possible to choose career over marriage, hotels over homes, patents over propriety. She showed that women could master complex technical fields without formal training, could build businesses without male partners, could succeed without conforming.

Every woman who’s ever filed a patent owes something to Henry. Every girl who’s ever taken apart a toy to see how it works follows in her footsteps. Every female engineer, inventor, or entrepreneur stands on foundations she built from soap and paper clips in Manhattan hotel rooms.

The Unfinished Revolution

Beulah Louise Henry died believing her work would inspire generations of women inventors. She was wrong—at least for several decades. The percentage of patents filed by women remained stagnant through the 1980s. Even today, women hold less than 20% of U.S. patents. The barriers Henry faced have shifted but haven’t disappeared.

Yet her story offers a different kind of inspiration now. In an era when we’re told that disruption requires venture capital, that innovation demands advanced degrees, that success means following established paths, Henry reminds us that the best inventions often come from outsiders who see problems insiders have learned to tolerate.

She proved that practical intelligence matters more than formal education. That solving real problems beats impressive engineering. That being excluded from the establishment might actually free you to think differently. That sometimes the best prototype is made from soap and paper clips, and the best laboratory is a hotel room.

The woman who lived in hotels and changed how America lived deserves more than a paragraph in history books. She deserves recognition as one of America’s greatest inventors—not greatest female inventor, just greatest inventor. She deserves credit for the industries she enabled, the products she pioneered, the barriers she broke.

But more than recognition, Beulah Louise Henry deserves imitators. Not people who’ll live in hotels and make prototypes from soap, but people who’ll question why things work the way they do. People who’ll see problems as opportunities. People who’ll ignore being told something’s impossible and build it anyway.

Because that’s what Beulah Louise Henry really invented: the idea that anyone, regardless of gender, education, or social approval, can look at the world and decide to fix it. One patent at a time. One prototype at a time. One impossible, incredible invention at a time.

The revolution she started isn’t finished. It’s barely begun.