Contents

ToggleEvery time you turn on your windshield wipers during a rainstorm, you’re using technology that exists because of Charlotte Bridgwood. While millions of drivers take this safety feature for granted, few know that a Canadian vaudeville actress created the first automatic windshield cleaning system in 1917. Her invention didn’t just improve visibility during bad weather – it fundamentally changed how cars could operate safely in all conditions.

Charlotte Bridgwood represents a pattern that appears throughout women’s history. She identified a dangerous problem that affected everyone who drove cars. She developed an innovative solution that worked better than existing options. She secured legal protection for her invention through the patent system. Then she watched as major corporations adopted her design without giving her credit or compensation.

She saw a future where driving could be safer for everyone, where women could be engineers and inventors, and where a single mother from Canada could revolutionize the automotive industry.

This story matters because it reveals how women’s contributions to automotive safety have been systematically erased from history. While Henry Ford gets credit for mass production and other men are remembered for engine innovations, the woman who made driving safe in bad weather has been forgotten. Her experience shows how gender bias in business and technology prevented women from receiving recognition for inventions that saved countless lives.

Growing Up in Canada’s Entertainment World

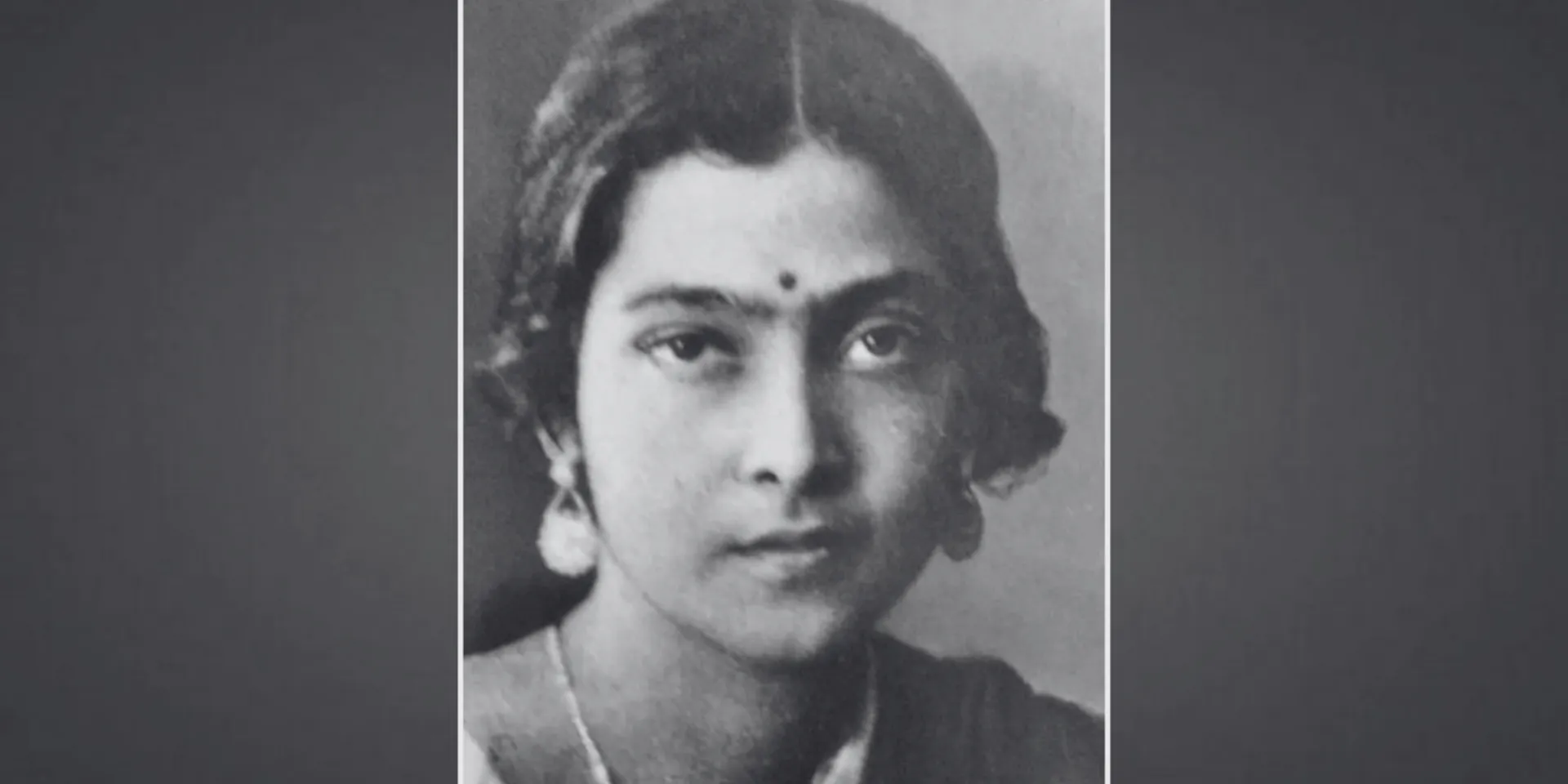

Charlotte Dunn was born on August 18, 1861, in Canada during a period when the country was developing its own cultural identity separate from Britain and the United States. Her family was involved in theater and entertainment, which gave her early exposure to performance and business management. This background would prove crucial to her later success as both an inventor and company president.

The entertainment industry in 1860s Canada was rough and demanding. Traveling theater companies moved from town to town, performing for audiences who expected high-quality shows despite limited resources and equipment. Success required creativity, adaptability, and practical problem-solving skills. Women in theater had to be particularly resourceful because they faced additional challenges related to social expectations and limited opportunities.

Charlotte’s childhood coincided with major technological changes that were transforming daily life. The telegraph was connecting distant cities, railroads were expanding across the continent, and new manufacturing processes were making consumer goods more affordable. These developments created opportunities for people who could identify practical problems and develop solutions.

Growing up in an entertainment family also meant learning about audience psychology and market dynamics. Successful performers had to understand what people wanted and deliver it consistently. They had to manage money carefully, maintain equipment, and adapt to changing conditions. These skills would later help Charlotte succeed as an inventor and business owner.

The theater world also exposed Charlotte to different types of people and ideas. Traveling performers met individuals from various social classes and backgrounds. They had to work with diverse groups of people and navigate complex social situations. This experience gave Charlotte insights into human behavior and market needs that would inform her later innovations.

Building a Career in Vaudeville Theater

When Charlotte married and took the name Bridgwood, she was already established as a performer using the stage name “Lotta Lawrence.” This name choice reflected the common practice of creating memorable, marketable identities for entertainment careers. The name “Lotta” suggested energy and enthusiasm, while “Lawrence” provided a respectable surname that audiences could remember easily.

As lead actress and manager of the Lawrence Dramatic Company, Charlotte handled both creative and business responsibilities. Managing a theater company required skills in budgeting, scheduling, marketing, personnel management, and logistics. She had to negotiate contracts with venues, coordinate travel arrangements, manage costumes and equipment, and ensure that shows met quality standards that would generate repeat business.

The vaudeville circuit in late 19th century North America was highly competitive. Hundreds of companies competed for bookings in the best theaters and most profitable cities. Success required not just talent but also business acumen and the ability to adapt quickly to changing market conditions. Charlotte’s company survived and thrived in this environment, indicating her effectiveness as both performer and manager.

During this period, Charlotte also gave birth to her daughter Florence, who would later become known as Florence Lawrence, one of the first major movie stars. Charlotte’s ability to maintain a successful theater career while raising a child demonstrated the kind of multitasking and time management skills that would later help her succeed as an inventor and manufacturer.

The theater business also taught Charlotte about the importance of timing and market positioning. Successful shows required understanding audience preferences, competitive dynamics, and technological trends. These insights would prove valuable when she later entered the automotive industry and had to position her inventions against established competitors.

The Early Days of Dangerous Driving

When automobiles began appearing on roads in the early 1900s, driving was an extremely hazardous activity. Cars had no safety features that modern drivers consider essential. There were no seat belts, no safety glass, no turn signals, and most importantly for Charlotte’s story, no effective way to clear windshields during rain or snow.

The windshield wipers that existed in the early 1910s were manual devices that required drivers to operate them by hand. Mary Anderson had patented a hand-operated wiper in 1905, but it required drivers to reach outside the car or use a lever inside the vehicle. This meant taking at least one hand off the steering wheel while trying to navigate in dangerous conditions.

The problems with manual wipers were obvious to anyone who drove in bad weather. Rain, snow, or mud on the windshield reduced visibility to nearly zero. Drivers had to choose between stopping frequently to clean their windshields manually or continuing to drive while nearly blind. Though having the former option was far better than having no windshield wipers at all and was quite therevolution for its time but it certainly wasn’t the most ideal one.

Most early car manufacturers viewed windshield cleaning as a minor problem that drivers would have to solve themselves. The automotive industry was focused on mechanical reliability, speed, and production costs. Safety features were considered luxury items that would increase prices and reduce sales to price-sensitive customers.

This attitude reflected broader assumptions about who would be driving cars and under what conditions. Early automobiles were mainly used by wealthy men for recreational driving in good weather. The idea that cars would become essential transportation for all types of people in all weather conditions seemed unlikely to most industry leaders. But not Charlotte.

Recognizing the Problem Through Personal Experience

Charlotte’s involvement with automobiles began through her success in entertainment and business. By the 1910s, she had accumulated enough wealth to afford a car, which put her among a small group of early adopters who understood both the potential and limitations of automotive technology.

As someone who traveled frequently for theater bookings, Charlotte experienced firsthand the dangers of driving in bad weather with inadequate windshield cleaning systems. She understood that poor visibility wasn’t just an inconvenience – it was a life-threatening safety issue that would only get worse as more people began driving cars.

Her experience managing a theater company had taught her to identify operational problems and develop systematic solutions. When she encountered the windshield wiper problem, she approached it with the same analytical mindset that had made her successful in entertainment business. She studied existing solutions, identified their limitations, and began thinking about improvements.

Charlotte also recognized that the windshield wiper problem would become more severe as automobile use expanded. She could see that cars were transitioning from luxury items for wealthy hobbyists to practical transportation for middle-class families. This meant that more people would be driving in all weather conditions, not just during pleasant recreational outings.

Her background in entertainment also gave her insights into consumer psychology that most inventors lacked. She understood that successful products needed to be not just functional but also convenient and reliable. Drivers wouldn’t adopt solutions that were complicated to use or prone to mechanical failure.

Developing the Electric Storm Windshield Cleaner

Charlotte’s approach to solving the windshield wiper problem was remarkably sophisticated for its time. Instead of simply improving existing manual systems, she reimagined the entire concept of windshield cleaning. Her invention used electric power to operate automatically, eliminating the need for driver intervention during operation.

The technical details of her system were innovative and practical. Rather than using blades that swept back and forth across the windshield, her design employed rollers that moved vertically to clean the glass surface. This roller system was powered by the car’s engine or a separate electric motor, making it the first truly automatic windshield cleaning device.

The roller design offered several advantages over blade systems. Rollers could conform better to curved windshield surfaces, providing more complete cleaning coverage. They were also less likely to scratch the glass or leave streaks that could impair visibility. The vertical motion was less conspicuous and distracting to drivers than the horizontal sweeping motion of blade wipers.

Charlotte’s system also included features that wouldn’t become standard in the automotive industry for decades. Her design incorporated variable speed controls that allowed drivers to adjust cleaning frequency based on weather conditions. This level of sophistication demonstrated her understanding of real-world driving conditions and user needs.

The engineering challenges involved in creating this system were substantial. Electric motors in 1917 were less reliable and more expensive than they would become later. Designing a system that could operate effectively in the harsh environment of an automobile required solving problems related to vibration, temperature extremes, and electrical reliability.

Founding the Bridgwood Manufacturing Company

Recognizing the commercial potential of her invention, Charlotte established the Bridgwood Manufacturing Company and became its president. This decision was remarkable for several reasons. First, very few women in 1917 were company presidents, especially in manufacturing industries. Second, the automotive supply industry was dominated by established male-owned businesses with strong relationships to car manufacturers.

HerWiki is built and maintained by the support of amazing readers like you. If this story inspired you, join the cause and help us make HerWiki bigger and better.

Charlotte’s decision to manufacture her invention herself rather than licensing it to existing companies reflected both ambition and strategic thinking. She understood that controlling manufacturing would give her more influence over product quality and marketing. It would also allow her to capture more of the economic value created by her invention.

Starting a manufacturing company required significant capital investment and technical expertise. Charlotte had to acquire or lease production facilities, purchase equipment, hire workers, and establish supply chains for raw materials. She had to develop quality control systems and figure out how to scale production from prototype to commercial quantities.

The technical challenges of manufacturing windshield wipers in 1917 were formidable. Precision metalworking required skilled workers and expensive equipment. Electrical components had to be assembled by hand with careful attention to reliability and safety. Each unit had to be tested to ensure it would function properly under automotive operating conditions.

Charlotte also had to develop marketing and sales strategies for a product that had no existing market category. Potential customers had no experience with automatic windshield cleaning systems and might be skeptical about their reliability and value. She had to educate the market while simultaneously building production capacity.

Navigating the Patent System

On October 2, 1917, Charlotte received U.S. Patent Number 1,240,432 for her “Electric Storm Windshield Cleaner.” This patent protected the key innovations in her design, including the roller mechanism and electric power system. Obtaining this patent required significant time, money, and legal expertise.

The patent application process in 1917 was complex and expensive, especially for inventors without connections to the established legal and business networks that dominated the automotive industry. Charlotte had to hire patent attorneys, prepare detailed technical drawings, and navigate bureaucratic procedures that were designed primarily for male inventors and corporate applicants.

Her patent application was remarkably comprehensive and technically sophisticated. It included detailed mechanical drawings, precise descriptions of component interactions, and claims that covered the essential features of automatic windshield cleaning. This level of detail suggested that Charlotte worked with skilled patent attorneys and understood the importance of strong intellectual property protection.

The patent gave Charlotte legal rights to her invention for a period of 17 years, which should have been enough time to establish a successful business and recover her investment. However, the patent was only as valuable as her ability to enforce it against infringers, which would require expensive litigation against well-funded corporate defendants.

The timing of her patent was both fortunate and problematic. It came just as the automotive industry was beginning to recognize the importance of safety features, but also just as World War I was disrupting normal business operations and creating material shortages that made manufacturing difficult.

The Challenge of Market Adoption

Despite the technical superiority of her invention, Charlotte faced enormous challenges in getting automotive manufacturers to adopt her windshield cleaning system. The car industry in 1917 was dominated by a small number of large companies that were focused on reducing costs and increasing production volumes rather than adding new features.

Most car manufacturers viewed windshield wipers as optional accessories that customers could purchase separately if they wanted them. This attitude reflected the industry’s focus on basic transportation rather than comfort or safety features. Adding standard equipment would increase production costs and complicate manufacturing processes that were optimized for simplicity and speed.

Charlotte’s invention also suffered from timing problems related to World War I. The war created shortages of materials like rubber and metals that were essential for manufacturing windshield wipers. It also diverted industrial capacity toward military production, making it difficult for small companies like Charlotte’s to compete for manufacturing resources.

The war also disrupted normal business relationships and marketing channels. Many potential customers and business partners were focused on war-related activities rather than civilian automotive improvements. This made it much harder for Charlotte to build the relationships needed to commercialize her invention successfully.

Additionally, Charlotte faced gender-based discrimination that made it harder for her to be taken seriously by male-dominated automotive companies. Many business executives in 1917 were reluctant to deal with women inventors or suppliers, preferring to work within established networks of male-owned businesses.

Financial Pressures and Patent Expiration

The combination of wartime disruptions, manufacturing challenges, and market resistance created severe financial pressures for Charlotte’s company. Manufacturing windshield wipers required significant upfront investment in equipment and inventory, but sales were slow and unpredictable. This cash flow problem was common among early automotive suppliers but particularly difficult for small companies without access to large amounts of capital.

By 1920, Charlotte was unable to maintain her patent fees, causing her patent protection to expire. This was a devastating blow because it meant that larger companies could now copy her design without paying licensing fees or facing legal consequences. The expiration of her patent essentially gave away the legal rights to her invention just as the automotive market was beginning to recognize the value of automatic windshield cleaning.

Patent maintenance fees in this era were designed to prevent patent holders from maintaining protection unless they were actively commercializing their inventions. The system was intended to ensure that valuable innovations didn’t remain locked up by inventors who couldn’t bring them to market. However, it also penalized inventors who faced temporary financial difficulties or market timing problems.

The loss of patent protection was particularly damaging because it came just as automotive technology was advancing to the point where electric windshield wipers were becoming practical and affordable. Improvements in electrical systems and manufacturing processes were making Charlotte’s invention more attractive to car manufacturers, but she could no longer benefit from these developments.

This situation illustrated a fundamental problem with the patent system that continues today. Individual inventors often lack the financial resources to maintain patent protection through the long development cycles required to commercialize complex technologies. This puts them at a disadvantage compared to large corporations that can afford to wait for market conditions to improve.

Corporate Adoption and Lost Recognition

In 1922, just two years after Charlotte’s patent expired, Cadillac became the first major automotive manufacturer to offer automatic windshield wipers as standard equipment. The timing was not coincidental – Cadillac was able to implement Charlotte’s design without paying licensing fees because her patent protection had lapsed.

Cadillac’s adoption of automatic windshield wipers was marketed as a major safety innovation that demonstrated the company’s commitment to advanced technology. The feature was popular with customers and helped differentiate Cadillac from competitors who still relied on manual wiper systems. This success led other manufacturers to quickly develop their own automatic wiper systems.

The rapid adoption of automatic windshield wipers after 1922 proved that Charlotte’s invention addressed a real market need. Within a few years, automatic wipers became standard equipment on most cars sold in North America and Europe. This widespread adoption created an enormous market that generated billions of dollars in revenue for automotive manufacturers and suppliers.

However, Charlotte received no recognition or compensation for her role in creating this technology. The automotive industry credited the development of automatic windshield wipers to the engineers and companies that commercialized the technology, not to the woman who invented the fundamental concepts years earlier.

This pattern of corporate appropriation of women’s inventions was common throughout the early 20th century. Women inventors often lacked the financial resources and business connections needed to commercialize their innovations successfully. When their patents expired or their companies failed, larger corporations would adopt their designs without acknowledging the original inventors.

The Broader Impact on Automotive Safety

Charlotte’s invention of automatic windshield wipers had consequences that extended far beyond improving visibility during rain storms. By making it safer to drive in bad weather, automatic wipers expanded the practical utility of automobiles and accelerated their adoption as primary transportation rather than recreational vehicles.

Before automatic wipers, many people avoided driving during rain or snow because of the safety risks associated with poor visibility. This limited the usefulness of cars and slowed the transition away from horses and public transportation. Automatic wipers made year-round driving practical for average consumers, which increased demand for automobiles and accelerated changes in urban planning and social patterns.

The safety improvements enabled by automatic windshield wipers also influenced the development of other automotive safety features. Once manufacturers recognized that safety equipment could be a selling point rather than just an added cost, they became more willing to invest in developing seat belts, safety glass, improved brakes, and other protective technologies.

Charlotte’s roller-based design, while not ultimately adopted by the industry, influenced the development of more effective windshield cleaning systems. Her insights about variable speed controls and automatic operation became standard features that are still used in modern cars. Her work helped establish the principle that safety equipment should operate automatically rather than requiring driver attention and manual operation.

The success of automatic windshield wipers also demonstrated the importance of user-centered design in automotive development. Charlotte’s invention succeeded because it addressed a real problem experienced by actual drivers, not just a theoretical engineering challenge. This focus on user needs became increasingly important as the automotive industry matured and began competing on features rather than just basic functionality.

The Hidden Economics of Women’s Innovation

Charlotte’s experience illustrates economic patterns that affected many women inventors during the early 20th century. Women often had good ideas and technical skills but lacked access to the capital, business networks, and legal resources needed to commercialize inventions successfully. This created opportunities for men and male-dominated corporations to appropriate women’s innovations without providing fair compensation.

The venture capital system that might have helped Charlotte finance her manufacturing company didn’t exist in 1917. Banks were reluctant to lend money to women-owned businesses, especially in technical industries. This forced women inventors to rely on personal savings or family resources, which limited their ability to scale production and compete with larger companies.

Women inventors also faced discrimination in patent law and business regulation. While women could legally obtain patents, the practical process of enforcing patent rights required resources and connections that were often unavailable to them. Legal proceedings were expensive and time-consuming, and judges and juries often had biases that favored male inventors and established corporations.

The loss of Charlotte’s patent protection due to maintenance fee problems was particularly damaging because it occurred just as market conditions were becoming favorable for her invention. This timing mismatch between innovation and commercialization was common among individual inventors but especially problematic for women who had fewer resources to weather extended development periods.

The economic value created by Charlotte’s invention ultimately flowed to automotive manufacturers and their predominantly male executives and shareholders. While millions of drivers benefited from improved safety, and the automotive industry generated enormous revenues from windshield wiper systems, Charlotte received none of the economic rewards from her innovation.

Family Legacy in Entertainment and Innovation

Charlotte’s daughter Florence Lawrence became one of the first major movie stars and was known as “The Biograph Girl” before becoming “The First Movie Star.” Florence’s success in the emerging film industry created a family legacy that spanned both entertainment and technology innovation. Like her mother, Florence would later develop automotive safety inventions, including early versions of turn signals and brake lights.

The parallel careers of Charlotte and Florence suggest that innovation and entrepreneurship were family values that were passed down across generations. Both women identified practical problems, developed technical solutions, and attempted to commercialize their inventions. Both also faced challenges related to gender discrimination and limited access to business resources.

Florence’s inventions, like her mother’s, were eventually adopted by the automotive industry without proper recognition or compensation. Her turn signal and brake light concepts became standard safety equipment, but she received little credit for originating these ideas. This pattern suggests that the problems Charlotte faced were systemic rather than individual.

The family’s success in entertainment provided financial resources and public visibility that helped support their technical innovation work. Charlotte’s theater career generated income that she could invest in her manufacturing company. Florence’s movie career gave her access to wealthy individuals who might have been potential investors or customers for automotive innovations.

However, success in entertainment also created expectations and time commitments that may have limited their ability to focus on technical innovation. Both women had to balance creative careers with invention and business activities, which required exceptional time management and energy levels.

Forgotten Contributions to Modern Convenience

Today, every car manufactured anywhere in the world includes automatic windshield wipers that operate based on principles that Charlotte Bridgwood invented in 1917. Modern wiper systems use electronic controls and sophisticated sensors, but they still rely on the fundamental concept of automatic operation that she pioneered more than a century ago.

The global windshield wiper industry now generates billions of dollars in annual revenue and employs hundreds of thousands of people in manufacturing, research, and development. This entire industry exists because Charlotte identified a safety problem and developed an innovative solution that made driving safer and more convenient for everyone.

Modern automotive safety regulations require that all cars include effective windshield cleaning systems. These regulations exist because safety experts recognize that poor visibility is a major cause of traffic accidents. Charlotte’s invention provided the technological foundation that made these safety standards possible.

The principles behind Charlotte’s roller-based cleaning system have also influenced the development of other automotive technologies. Similar concepts are used in automatic car wash equipment, industrial cleaning systems, and other applications where automatic operation is preferred over manual control.

Advanced driver assistance systems in modern cars include rain sensors that automatically activate windshield wipers when they detect moisture on the windshield. These systems represent the evolution of Charlotte’s insight that windshield cleaning should be automatic rather than dependent on driver attention and manual operation.

Recognition and Legacy

Charlotte Bridgwood died on August 20, 1929, just two days after her 68th birthday. By that time, automatic windshield wipers had become standard equipment on most cars, but she received no recognition for her role in creating this technology. Her death occurred during the early years of the Great Depression, when economic hardship overshadowed many individual achievements and contributions.

Charlotte Bridgwood revolutionized automotive safety while the industry pretended she didn’t exist. Her automatic windshield wiper and other innovations saved countless lives and established principles of user-centered design that guide modern engineering. Her story reveals how individual brilliance can create lasting change even when systems of discrimination try to erase those contributions.

More importantly, Charlotte’s life demonstrates the interconnections between different forms of innovation. Her theatrical management skills informed her engineering work. Her understanding of performance psychology shaped her approach to user design. Her financial independence from entertainment enabled her technical pursuits. She proved that innovation doesn’t require formal credentials or institutional support – it requires vision, determination, and refusal to accept limitations.

The automotive industry eventually adopted every significant innovation Charlotte pioneered, from automatic windshield wipers to integrated safety systems. They profited enormously from her ideas while denying her credit or compensation. But Charlotte’s true victory was in proving that women could excel in technical fields despite every barrier placed in their path.

Today, when we drive safely through storms with automatic wipers maintaining our visibility, we’re using technology that Charlotte Bridgwood envisioned over a century ago. Her ghost haunts every automotive safety feature, reminding us that progress comes from those brave enough to challenge systems that insist they don’t belong.

Charlotte transformed from vaudeville performer to automotive pioneer not because she was exceptional, but because she refused to be limited by others’ expectations. She saw problems that male engineers ignored and developed solutions they couldn’t imagine. In doing so, she didn’t just invent the automatic windshield wiper – she invented a new possibility for what women could achieve in technical fields.

Her story demands that we question how many other Charlotte Bridgwoods have been erased from history, how many innovations we’ve credited to the wrong people, and how many problems remain unsolved because we exclude those who see differently. Charlotte’s legacy isn’t just in the safety features we use daily, but in the reminder that revolution can come from unexpected sources – even from a vaudeville performer who dared to imagine a safer way to drive through the storm.