Contents

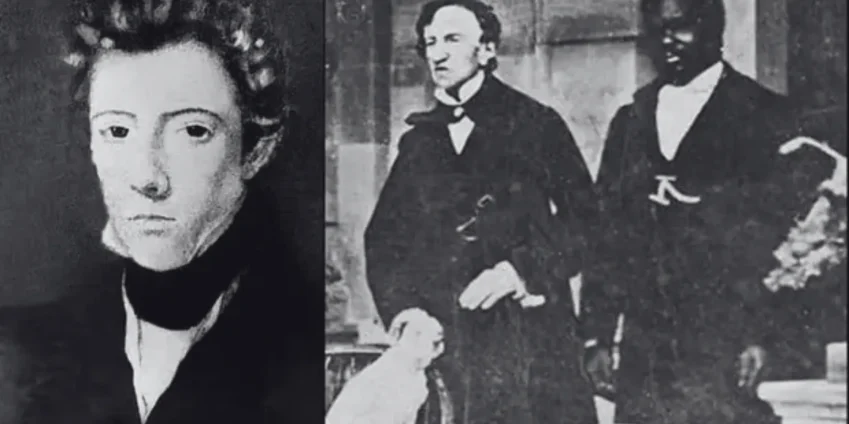

ToggleFor fifty-six years, one of the British Empire’s most skilled surgeons walked hospital corridors, saved countless lives, and revolutionized medical practice across three continents. Colleagues knew this doctor as James Barry – a brilliant, temperamental physician who performed the first successful cesarean section in Africa and fought tirelessly for better conditions for soldiers, prisoners, and the poor.

What they didn’t know was that James Barry had been born Margaret Ann Bulkley in Cork, Ireland, around 1789. This wasn’t just a case of a woman disguising herself as a man. This was a complete transformation of identity that allowed one person to achieve what would have been impossible for a woman in the early 1800s – becoming one of the most accomplished military surgeons in British history.

Margaret’s story reveals how rigid gender barriers forced extraordinary women to literally become men to pursue their ambitions. More importantly, it shows how one person’s determination to practice medicine changed healthcare for millions of people across the British Empire. Without Margaret Ann Bulkley’s decision to become James Barry, modern surgical techniques, hospital sanitation, and patient care might have developed decades later.

Growing Up Poor in Cork

Margaret Ann Bulkley was born into a world that offered women few choices. Her father Jeremiah ran a weigh house in Cork’s busy Merchant’s Quay, where ships brought goods from around the world. Her mother Mary Anne came from a more artistic family – her brother James Barry was becoming famous as a painter in London.

But the Bulkley family’s comfortable middle-class life collapsed when Margaret was still young. Anti-Catholic sentiment in Ireland cost Jeremiah his job at the weigh house. He tried other business ventures but failed repeatedly. His poor decisions and bad luck with money eventually landed him in Dublin’s Marshalsea debtors’ prison.

This left Mary Anne alone with Margaret and their older son John. They had no income, no husband and father to support them, and few options for survival. John eventually abandoned his legal studies to join the military, leaving his mother and sister to fend for themselves.

The family’s financial ruin taught Margaret early lessons about how quickly security could disappear. She watched her mother struggle with problems that had no good solutions. Women couldn’t earn decent living. They couldn’t attend universities. They couldn’t practice professions like law or medicine. They depended entirely on men for financial support, and when that support disappeared, they faced poverty or worse.

Mary Anne tried reaching out to her successful brother James in London, but he had cut off contact with his Irish family decades earlier. The famous painter wanted nothing to do with his sister’s problems. This rejection forced Mary Anne and Margaret to survive on their own in a society that offered women almost no opportunities for independence.

The Mystery of Juliana

One of the strangest aspects of Margaret’s early life involves her younger sister Juliana. Official records show Juliana as Margaret’s sister, but some evidence suggests she might actually have been Margaret’s daughter.

After Margaret’s death, the woman who prepared the body claimed she found stretch marks indicating Margaret had given birth when very young. This led some historians to speculate that Margaret had been sexually assaulted as a child and that Juliana was the result.

However, other evidence suggests this theory is probably wrong. Around the time Juliana would have been conceived, Jeremiah Bulkley threw his wife and daughter out of their home. He later wrote letters about “forgiving” his wife for something. This suggests that if anyone had an affair, it was probably Mary Anne, not Margaret.

The truth about Juliana remains unknown, but the speculation reveals something important about Margaret’s world. People found it easier to believe that a young girl had been assaulted than that a woman might have had an affair. They also assumed that any pregnancy must have been the woman’s fault, whether through assault or adultery.

What matters more is how this family crisis affected Margaret’s understanding of women’s vulnerability. She saw how quickly a woman could lose everything – home, security, reputation – based on circumstances beyond her control. She watched her mother struggle with problems that society blamed on women’s supposed moral weakness rather than on systems that gave women no power or protection.

Escape to London and a Dangerous Plan

In 1804, fifteen-year-old Margaret and her mother left Ireland for London. They hoped that James Barry’s death might have changed the family situation, and they were right. The famous painter died in 1806, leaving money and property that helped support Mary Anne and Margaret.

More importantly, James Barry’s death brought them into contact with his influential friends. These men were liberals who believed in social reform and expanding opportunities for talented people regardless of their backgrounds. General Francisco de Miranda was fighting for South American independence. Edward Fryer was an educator who believed in merit over birth. Daniel Reardon was a lawyer who handled progressive causes.

These men saw potential in young Margaret. She was intelligent, well-read, and eager to learn. But they also understood the limitations she faced as a woman. No matter how brilliant she might be, she could never attend university, practice medicine, or pursue any profession that might use her talents.

Sometime around 1809, an extraordinary plan took shape. Margaret would become a man. Not just dress as a man temporarily, but completely transform her identity and live as a man for the rest of her life. She would become the nephew of the late James Barry, taking his name and his background.

This wasn’t a simple disguise. This was a complete reconstruction of identity that would require constant vigilance and perfect acting for decades. One mistake, one moment of carelessness, and everything would be lost. Margaret would face imprisonment, disgrace, and complete ruin.

The plan succeeded because Margaret’s allies understood how to manipulate social expectations. Young men in the early 1800s often looked feminine and delicate. Many didn’t develop deep voices or facial hair until their late teens or early twenties. A short, slight person with smooth skin and a high voice could pass as a boy who hadn’t reached full maturity yet.

Becoming James Barry

On November 30, 1809, Margaret Anne Bulkley and her mother boarded a ship to Edinburgh. When they arrived, Margaret had become James Barry, nephew of the late painter. This transformation required more than just changing clothes and names. Margaret had to learn to walk, talk, and behave like a man in a society where gender roles were strictly defined.

The University of Edinburgh Medical School was one of the best in the world, but it was also dangerous territory for someone hiding their birth sex. Medical students lived together, studied anatomy together, and often shared rooms and meals. Any student who seemed different faced intense scrutiny from classmates and professors.

Margaret managed the deception brilliantly. She explained her youthful appearance and high voice by claiming to be younger than she actually was. She avoided situations where her body might be exposed by being private about bathing and dressing. She cultivated a personality that was confident, opinionated, and sometimes aggressive – traits that people associated with young men trying to prove their masculinity.

Her medical studies went well despite the constant stress of maintaining her disguise. She learned surgery, anatomy, and clinical practice while constantly worrying that someone might discover her secret. The University Senate initially tried to block her final examinations because they thought she looked too young, but influential friends intervened and she graduated with her medical degree in 1812.

The graduation marked a crucial milestone. Margaret had not only survived three years of medical school while hiding her birth sex, but she had excelled academically. She was now Dr. James Barry, qualified to practice medicine anywhere in the British Empire. But the real test was still ahead – could she maintain her disguise while actually working as a doctor?

Joining the Army and Early Challenges

After graduation, Margaret moved to London for additional surgical training at Guy’s and St Thomas’ hospitals. She studied under some of Britain’s most famous surgeons, including Astley Cooper, who was known for groundbreaking operations and innovative techniques.

In July 1813, she passed the examination of the Royal College of Surgeons and immediately joined the British Army as a Hospital Assistant. This decision was strategic – the military offered opportunities for advancement based on skill rather than family connections. It also provided a structured environment where her unusual behavior might be seen as military discipline rather than suspicious oddity.

The early army years were difficult. Margaret had to prove herself capable while avoiding the close scrutiny that military life inevitably brought. She served first in Chelsea and then at the Royal Military Hospital in Plymouth. Her colleagues found her prickly and argumentative, but they also recognized her surgical skill and dedication to patients.

Military service also provided something Margaret desperately needed – distance from people who might have known her before her transformation. In army hospitals far from Cork and London, she could be James Barry without worrying about encounters with family friends or childhood acquaintances.

Her promotion to Assistant Surgeon in December 1815 confirmed that her medical abilities were being recognized despite her difficult personality. But the real test came with her first overseas posting to Cape Town, South Africa, in 1816. This assignment would either establish her career or destroy it entirely.

Revolutionary Changes in Cape Town

Cape Town in 1816 was a rough colonial outpost where British officials struggled to maintain control over Dutch settlers, indigenous populations, and enslaved people. Medical care was primitive even by early 19th-century standards. Military hospitals were overcrowded, unsanitary, and often deadly for patients who might have survived their original injuries or illnesses.

HerWiki is built and maintained by the support of amazing readers like you. If this story inspired you, join the cause and help us make HerWiki bigger and better.

Margaret’s transformation of Cape Town’s medical system began with a stroke of luck that demonstrated her surgical abilities. Lord Charles Somerset, the colony’s governor, had a sick daughter whom local doctors couldn’t help. Margaret successfully treated the child, earning the governor’s gratitude and trust.

This relationship with Somerset became crucial to Margaret’s success. The governor gave her extraordinary authority to reform medical practices throughout the colony. She used this power to implement changes that saved thousands of lives and established new standards for military medicine.

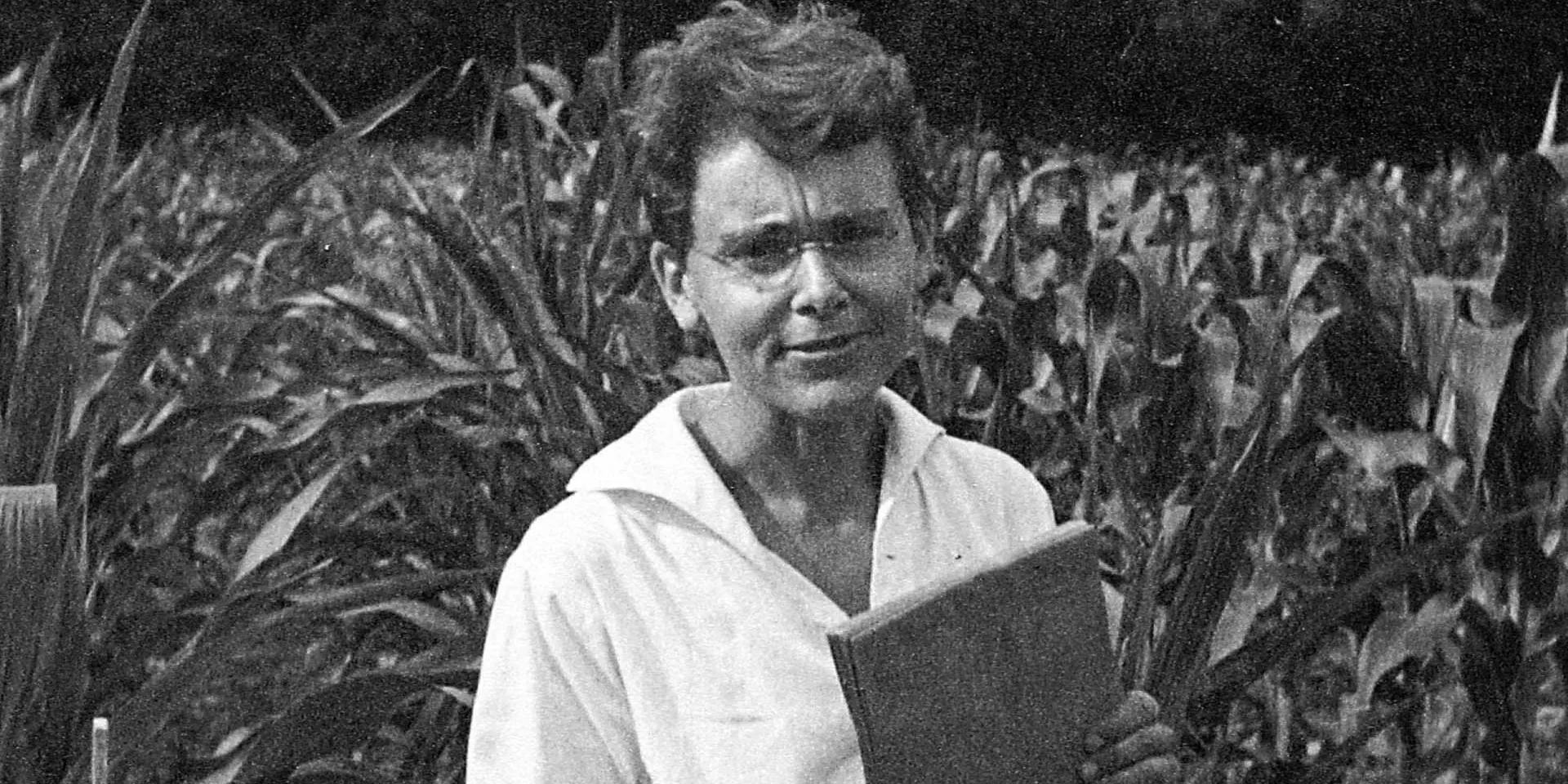

Her first target was hospital sanitation. She ordered the removal of sewage and garbage that had accumulated around military medical facilities. She insisted on clean bedding, regular washing of surgical instruments, and proper ventilation in patient wards. These measures dramatically reduced infection rates and death rates among soldiers.

But Margaret went beyond treating military personnel. She demanded better medical care for enslaved people, prisoners, and indigenous populations. This was revolutionary thinking in a colonial society built on racial exploitation. Most British officials saw these groups as expendable labor rather than human beings deserving medical attention.

Her most famous achievement was performing one of the first successful cesarean sections in Africa where both mother and child survived. This operation required extraordinary surgical skill and demonstrated advanced understanding of anatomy and sterile technique. The child was named James Barry Munnik in her honor, and the name passed down through generations, eventually reaching a future Prime Minister of South Africa.

Fighting the System Across the Empire

Margaret’s success in Cape Town led to postings across the British Empire where she continued revolutionizing medical practice while battling conservative officials who resisted change. In Mauritius, Jamaica, Saint Helena, the West Indies, Malta, Corfu, and Canada, she implemented the same reforms that had worked in South Africa.

Each posting brought new challenges. Local administrators often resented being told how to run their colonies by an army doctor. Fellow officers sometimes tried to undermine her authority through bureaucratic sabotage or personal attacks. But Margaret’s combination of medical expertise, political connections, and sheer stubbornness usually prevailed.

Her methods were often confrontational. She wrote scathing reports about incompetent officials. She publicly criticized colonial policies that harmed public health. She refused to compromise on standards even when doing so would have made her life easier. This approach made her many enemies but also saved countless lives.

In Malta, she dealt with a cholera epidemic by implementing quarantine measures and improving water sanitation. Her quick action contained the outbreak and prevented thousands of deaths. In Canada, she fought for better food and medical care for prisoners and lepers, groups that most officials preferred to ignore.

Throughout her career, she maintained strict personal habits that supported her disguise while also reflecting her medical knowledge. She was completely vegetarian and refused to drink alcohol. She kept most personal relationships at a distance while remaining devoted to her pets, particularly a poodle named Psyche.

The Crimean War Confrontation

One of the most revealing incidents in Margaret’s career occurred during the Crimean War when she clashed with Florence Nightingale, the famous nursing reformer. This confrontation highlighted the different approaches these two women took to improving medical care.

Nightingale was working within acceptable gender roles, using her position as a respectable lady to advocate for nursing reforms. Margaret was operating completely outside gender expectations, wielding the authority of a male army surgeon to demand systemic changes.

Their argument apparently occurred in a hospital courtyard where Margaret publicly berated Nightingale for some aspect of hospital management. Nightingale later described the encounter as the worst public scolding she had ever received. She noted that everyone else involved behaved like gentlemen while Margaret behaved “like a brute.”

Only after Margaret’s death did Nightingale learn that her antagonist had been a woman. This revelation forced her to reconsider the encounter. Had she witnessed a woman using male authority to advocate for medical improvements? Or had she simply met an unusually difficult army surgeon who happened to be female?

The confrontation reveals the complexity of Margaret’s position. She had gained the authority to make real changes in military medicine, but only by completely abandoning her identity as a woman. She could save lives and improve conditions, but only by becoming someone she had never been born to be.

The Secret Behind Closed Doors

Maintaining her disguise for fifty-six years required constant vigilance and careful planning. Margaret developed elaborate routines to avoid exposure while living and working in close quarters with male colleagues.

She never allowed anyone in her room while dressing or undressing. She gave standing orders that in case of her death, her body should be buried in bed sheets without examination. She cultivated a reputation for privacy that made her colleagues respect her boundaries without becoming suspicious.

Her relationships with other people remained carefully controlled. She maintained professional distance from most colleagues while developing a few close friendships with people who seemed to accept her eccentricities without investigation. Her longest relationship was with a black servant she first employed in South Africa who stayed with her until her death.

Some historians have speculated about Margaret’s romantic relationships, particularly her close friendship with Lord Charles Somerset in Cape Town. Contemporary rumors suggested a sexual relationship between the two men, but these allegations were never proven and may have been political attacks on Somerset’s administration.

The truth about Margaret’s personal life remains largely hidden. She successfully protected her most important secret while maintaining a public persona that allowed her to practice medicine at the highest levels of the British military establishment.

Death and Discovery

Margaret retired from the army in 1859 and spent her final years quietly in London. She died of dysentery on July 25, 1865, at the age of seventy-six. Her death should have been a routine matter – the burial of a retired army surgeon with a distinguished but unremarkable career.

Instead, her death became a scandal that shocked British society and challenged fundamental assumptions about gender, identity, and achievement. The discovery of her birth sex happened because of a dispute over payment for preparing her body for burial.

The charwoman who laid out Margaret’s corpse tried to collect additional fees from Margaret’s physician, Major D.R. McKinnon. When he refused to pay, she revealed that the body had been biologically female and showed signs of having borne a child. McKinnon initially dismissed these claims, but the woman persisted and eventually took her story to the press.

The revelation created a sensation in Victorian Britain. Newspapers struggled to explain how a woman could have practiced medicine and achieved high military rank while maintaining a male identity for decades. Some people claimed they had always suspected something unusual about James Barry, but most who had known Margaret expressed complete surprise.

The British Army immediately sealed Margaret’s military records for one hundred years, hoping to suppress the scandal. But the story had already spread too widely to contain. Margaret’s deception had succeeded too well and lasted too long to be quietly covered up.

The Intersex Theory and Its Problems

Some modern commentators have suggested that Margaret might have been intersex rather than simply a woman living as a man. This theory argues that someone with ambiguous genitalia or other intersex conditions could have maintained a male identity more easily than someone who was clearly female.

Major McKinnon, Margaret’s physician, mentioned in his correspondence that he didn’t know whether Margaret was “male, female, or hermaphrodite.” Some historians have seized on this statement as evidence for the intersex theory.

However, this interpretation faces several problems. McKinnon was writing defensively after being publicly embarrassed by the charwoman’s revelations. His mention of hermaphroditism may have been an attempt to explain away his failure to detect Margaret’s birth sex during medical examinations.

More importantly, the intersex theory misses the point of Margaret’s achievement. Whether she was born female or intersex, she successfully challenged gender barriers that prevented people assigned female at birth from pursuing medical careers. Her accomplishments came from skill, determination, and courage, not from biological advantages.

The focus on Margaret’s anatomy also reflects uncomfortable assumptions about women’s capabilities. Some people seem more comfortable believing that Margaret must have been biologically unusual rather than accepting that a woman could achieve so much in a male-dominated field.

Margaret’s impact on medicine extended far beyond her personal achievement of practicing as a woman. Her innovations in hospital sanitation, surgical technique, and patient care established new standards that saved countless lives throughout the British Empire.

Her insistence on clean facilities, proper nutrition, and humane treatment for all patients challenged medical practices that were often indifferent to suffering. She understood that healing required more than just surgical skill – it demanded attention to the total environment in which patients recovered.

Her advocacy for marginalized populations was particularly revolutionary. In colonial societies built on exploitation, she demanded medical care for enslaved people, prisoners, and indigenous populations. She recognized that public health required protecting everyone, not just privileged groups.

Her vegetarian diet and abstinence from alcohol reflected advanced understanding of nutrition and health that was decades ahead of mainstream medical thinking. She practiced preventive medicine by maintaining lifestyle habits that supported her own health and longevity.

Her successful cesarean section in Cape Town demonstrated surgical abilities that few contemporary surgeons possessed. This operation required precise anatomical knowledge, steady hands, and understanding of sterile technique that saved the lives of both mother and child.

Many medical practices that we take for granted today can be traced back to reforms that Margaret implemented across the British Empire. Her emphasis on hospital sanitation established principles that became standard practice decades later when germ theory gained acceptance.

Her attention to nutrition and patient care anticipated modern understanding of holistic medicine. She recognized that healing required addressing patients’ total physical and psychological needs, not just treating specific injuries or diseases.

Her advocacy for public health measures like clean water and waste management prevented disease outbreaks that could have killed thousands of people. These interventions had lasting effects on colonial societies that extended far beyond Margaret’s military career.

Her surgical innovations, particularly her successful cesarean section, demonstrated techniques that other surgeons later adopted and refined. Her willingness to attempt dangerous operations when necessary saved lives and advanced surgical knowledge.

Her administrative reforms in military hospitals established organizational systems that improved efficiency and patient outcomes. Her reports and recommendations influenced military medical policy throughout the British Empire.

Margaret’s success came at enormous personal cost that reveals the brutal reality of gender restrictions in the early 1800s. She could never have intimate relationships, raise children openly, or even express her authentic identity without risking everything she had achieved.

The constant stress of maintaining her disguise must have been exhausting. Every interaction with colleagues, every medical examination of patients, every social gathering required careful attention to behavior that might reveal her secret. One careless moment could have destroyed her career and reputation.

She also faced the psychological burden of living as someone she had never been born to be. Whatever her personal feelings about gender identity, she had to perform masculinity convincingly enough to fool thousands of people over fifty-six years.

Her isolation from other women meant she could never share her experiences with people who might understand the unique challenges she faced. She had no role models, no support network, and no one who could advise her on managing the complexities of her situation.

Yet despite these costs, Margaret apparently considered the sacrifice worthwhile. She maintained her male identity until death, suggesting that the opportunity to practice medicine and save lives justified the personal price she paid.