Contents

ToggleArtemisia Gentileschi picked up a paintbrush at age 15 and never put it down. For nearly four decades, she created art that made powerful men nervous and other women feel seen. She painted biblical heroines slaying their oppressors with the same skill other artists used to paint pretty flowers. She built an international career in an industry that barely allowed women to hold a brush. She survived public humiliation, raised children alone, and died wealthy enough to own property in three countries.

Her story matters because she proved something the art world refused to believe: women could paint just as powerfully as men, think just as strategically about business, and create images that would outlast empires. She did this during the 1600s, when women couldn’t vote, couldn’t own property independently, and couldn’t get formal art training. Yet she became the first woman admitted to Florence’s prestigious art academy and built a client list that included kings and cardinals.

Today, her paintings hang in major museums worldwide. Art historians call her one of the most important Baroque painters, male or female. But for centuries, her artistic genius was overshadowed by gossip about her personal life. She transformed her trauma into some of the most powerful paintings of the Baroque period, created a career that spanned four countries and five decades, and left behind a body of work that challenged every assumption about what women could achieve in art.

Growing Up in Paint and Poverty

Artemisia Lomi was born in Rome on July 8, 1593, into a family where art was survival. Her father Orazio Gentileschi painted for wealthy patrons who paid enough to keep food on the table but not enough to guarantee security. Her mother Prudenzia died when Artemisia was 12, leaving her father to raise four children while building his career.

Rome in the 1590s was experiencing an artistic revolution. Caravaggio had just introduced his dramatic style of painting, using real people as models and creating scenes lit by stark, theatrical lighting. This approach shocked the art establishment, which preferred idealized figures and smooth, polished surfaces. Orazio Gentileschi became one of Caravaggio’s followers, adapting the master’s techniques to his own vision.

Artemisia grew up surrounded by this artistic ferment. She watched her father grind pigments, prepare canvases, and negotiate with difficult clients. She learned that art was both creative expression and commercial enterprise. Unlike her brothers, who showed little interest in painting, Artemisia absorbed everything. She learned to mix colors that glowed with inner light, to paint fabric that looked real enough to touch, and to capture human emotions with startling accuracy.

By age 15, she was producing work sophisticated enough to sell. This was extraordinary for any teenager, but especially for a girl in 17th-century Italy. Most women who became artists did so as amateurs, painting portraits of family members or copying religious scenes. Professional female artists were so rare that when they emerged, they were treated as curiosities rather than serious practitioners.

Artemisia’s earliest surviving painting, “Susanna and the Elders” from 1610, shows remarkable maturity for a 17-year-old artist. The biblical story depicts an older woman being sexually harassed by two men who threaten to destroy her reputation unless she submits to them. Most male artists painted this scene to titillate viewers, focusing on Susanna’s nudity rather than her distress. Artemisia painted genuine fear and revulsion on Susanna’s face, making viewers confront the woman’s anguish rather than enjoy her vulnerability.

This approach would define Artemisia’s career. She consistently portrayed women as complex human beings rather than decorative objects. Her female figures think, feel, and act with agency. They’re not passive victims or idealized beauties, but real people facing real challenges with courage and intelligence.

The Trial That Changed Everything

In 1611, when Artemisia was 18, her life exploded into public scandal. Agostino Tassi, a painter working with her father, raped her in the family home. When Tassi refused to marry her afterward (which would have restored her “honor” according to social customs), Orazio pressed criminal charges.

The seven-month trial became a sensation in Rome. Court records, which survive today, provide brutal details about both the assault and the legal proceedings. Artemisia was tortured with thumb screws to verify her testimony, a standard but horrific practice designed to ensure witness truthfulness. As the metal devices crushed her fingers, she reportedly looked at Tassi and said, “This is the ring you give me, and these are your promises.”

The trial revealed that Tassi was already married, had committed adultery with his sister-in-law, and had plotted to steal paintings from Orazio’s workshop. Despite this evidence, he received only a light sentence of exile from Rome, which was never enforced. The real punishment fell on Artemisia, whose reputation was permanently damaged by the public proceedings.

Most women in her position would have disappeared from public life, either entering a convent or retreating into domestic obscurity. Artemisia did the opposite. She used the notoriety to build her career, turning scandal into professional opportunity. She understood that being talked about, even negatively, was better than being ignored.

The trial also influenced her art in complex ways. She began painting more scenes of women triumphing over male oppressors, particularly the story of Judith beheading the Assyrian general Holofernes. Art historians debate whether these paintings represent personal revenge fantasies or simply reflected popular themes that sold well to collectors. The truth is probably both. Artemisia was too smart to let personal trauma limit her artistic range, but she was also human enough to find satisfaction in painting powerful women destroying evil men.

Building a Career in Florence

One month after the trial ended, Artemisia married Pierantonio Stiattesi, a minor artist from Florence. This marriage was likely arranged by her father to repair her damaged reputation and provide social protection. The couple moved to Florence, where Artemisia would spend the next six years building the foundation of her international career.

Florence in the 1610s was ruled by the Medici family, sophisticated patrons who collected art, sponsored scientific research, and promoted cultural innovation. The city attracted artists, writers, musicians, and scholars from across Europe. For an ambitious painter like Artemisia, Florence offered opportunities that Rome couldn’t match.

She quickly established herself in Florentine society, becoming friends with other artists and gaining the attention of wealthy collectors. In 1614, she became the first woman admitted to the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno, Florence’s official artists’ academy. This membership was more than honorary recognition; it provided professional legitimacy and access to important commissions.

The Medici family became her most important patrons. Cosimo II de’ Medici commissioned multiple paintings, and his mother Christina of Lorraine became a personal supporter. Through these connections, Artemisia met Galileo Galilei, who was then working under Medici patronage. Their correspondence shows a relationship of mutual respect between two innovators who understood what it meant to challenge established thinking.

During her Florence years, Artemisia painted some of her most famous works. Her 1614-1620 version of “Judith Slaying Holofernes,” now in the Uffizi Gallery, demonstrates her complete mastery of Baroque techniques. The painting shows Judith and her maidservant decapitating the sleeping general with brutal efficiency. The violence is graphic but not gratuitous; every detail serves to emphasize the women’s determination and competence.

What makes this painting extraordinary is its psychological complexity. Judith’s face shows concentration rather than bloodlust. She’s performing a necessary but unpleasant task with professional skill. Her maidservant assists with calm efficiency, suggesting this is planned cooperation rather than emotional outburst. The composition emphasizes the women’s teamwork and shared purpose, making their actions seem both justified and inevitable.

Artemisia also painted more conventional subjects during this period, including religious scenes and portraits. Her “Self-Portrait as a Lute Player” shows her musical accomplishments and social sophistication. She presents herself as an educated, cultured woman who happened to be an artist, not as an exotic curiosity. This careful image management was crucial for maintaining her reputation and attracting respectable clients.

Personal Life and Professional Challenges

While building her career, Artemisia faced the same challenges that confronted all working mothers: balancing professional demands with family responsibilities. She and Pierantonio had five children during their Florence years, though only one daughter, Prudentia, survived to adulthood. Child mortality was common in the 17th century, but the repeated losses must have been devastating.

Recently discovered letters reveal that Artemisia had a passionate affair with Francesco Maria Maringhi, a wealthy Florentine nobleman. These letters show a woman of strong emotions and clear intelligence, capable of deep feeling while remaining focused on practical concerns. She writes about love, money, family problems, and professional opportunities with equal directness.

Her husband Pierantonio apparently knew about the affair and tolerated it, possibly because Maringhi provided financial support during difficult periods. This arrangement reflects the complicated reality of marriage and money in 17th-century Italy. Artemisia’s letters suggest she viewed the relationship pragmatically, as one source of security among many rather than the center of her emotional life.

The affair eventually caused problems when rumors spread through Florence’s court society. Combined with ongoing financial difficulties, these scandals led Artemisia and Pierantonio to leave Florence around 1620. They returned to Rome, where Artemisia would spend the next phase of her career rebuilding her reputation and expanding her artistic range.

Roman Recognition and Venetian Ventures

Back in Rome, Artemisia found an art world transformed by new patrons and changing tastes. The Catholic Church was commissioning massive decorative projects to demonstrate papal power and religious authority. Private collectors were seeking smaller works that showcased technical skill and intellectual sophistication. Foreign visitors, especially wealthy English and French tourists, were buying Italian art to take home as souvenirs of their travels.

Artemisia positioned herself to serve all these markets. She painted religious scenes for church patrons, mythological subjects for educated collectors, and portraits for foreign visitors. Her technical skills had reached full maturity, allowing her to work in multiple styles depending on client preferences. She could paint with Caravaggio’s dramatic lighting, the Venetian masters’ rich colors, or the classical restraint preferred by conservative patrons.

During this period, she developed relationships with other artists working in Rome. Simon Vouet, a French painter, became both collaborator and competitor. They influenced each other’s work and shared information about potential commissions. These professional friendships were crucial for navigating Rome’s complex art market, where success depended as much on personal connections as artistic ability.

Around 1627, Artemisia moved to Venice for three years. The city offered different opportunities and challenges than Rome or Florence. Venetian collectors prized color and sensual beauty over dramatic storytelling. They wanted paintings that would look magnificent in their palaces rather than images that challenged viewers intellectually or emotionally.

Artemisia adapted her style accordingly, creating works like “The Sleeping Venus” that emphasized beauty and luxury over psychological complexity. These paintings showed her versatility as an artist while providing financial rewards that allowed her to maintain her independence. She understood that artistic integrity didn’t require stylistic rigidity; a true professional could work in whatever mode the situation demanded.

HerWiki is built and maintained by the support of amazing readers like you. If this story inspired you, join the cause and help us make HerWiki bigger and better.

The Naples Workshop and European Fame

In 1630, Artemisia moved to Naples, which would remain her primary base for the rest of her career. The city was then one of Europe’s largest, a cosmopolitan center where Spanish, Italian, French, and other cultural traditions mixed freely. Naples offered both wealthy local patrons and international visitors seeking high-quality art.

Artemisia established a workshop that produced paintings for clients throughout Europe. She employed assistants who could handle routine work while she focused on major commissions and original compositions. This business model allowed her to increase production without compromising quality on her most important pieces.

Her Naples workshop became known for religious paintings that combined technical excellence with emotional power. She painted multiple versions of popular subjects like Mary Magdalene, Saint Catherine, and the Annunciation. Each version was individually crafted rather than mechanically reproduced, showing subtle variations that reflected different clients’ preferences.

During this period, Artemisia’s reputation spread throughout Europe. In 1638, she was invited to London to work for King Charles I, one of the era’s most sophisticated art collectors. Charles had assembled a magnificent collection that included works by Titian, Rubens, and Van Dyck. Artemisia’s inclusion in this group represented the pinnacle of professional recognition.

She worked in London for four years, collaborating with her father on decorative projects for the royal palaces. The experience exposed her to different artistic traditions and working methods while providing access to an international network of collectors and dealers. When political tensions led to the English Civil War, she returned to Naples, but maintained correspondence with English patrons who continued commissioning works.

Innovation in Business and Art

Throughout her career, Artemisia demonstrated remarkable business acumen that complemented her artistic talents. She understood how to price her work, negotiate with difficult clients, and manage multiple projects simultaneously. Her letters reveal someone who thought strategically about career development while maintaining artistic standards.

She was among the first artists to develop what we would now call a personal brand. Her paintings were immediately recognizable not just for their technical quality but for their distinctive approach to subject matter. Clients hired Artemisia Gentileschi because they wanted paintings that looked like Artemisia Gentileschi paintings, not generic examples of current styles.

This brand identity centered on her ability to paint powerful women with psychological complexity and physical presence. Her female figures occupy space confidently, think independently, and act decisively. They represent ideals of feminine strength that resonated with both male and female patrons, though perhaps for different reasons.

Artemisia also innovated in her working methods. While most artists of her era worked alone or with a single apprentice, she developed a workshop system that allowed for greater productivity without sacrificing quality. She trained assistants to handle background details and preliminary work while maintaining personal control over faces, hands, and other crucial elements.

Her business correspondence shows sophisticated understanding of market dynamics. She adjusted her prices based on client wealth, deadline pressures, and painting complexity. She offered payment plans for major commissions and provided detailed written descriptions of proposed works to avoid misunderstandings. These practices became standard in the art world but were innovative when Artemisia introduced them.

The Final Years and Legacy

Artemisia’s later career was marked by continued productivity and growing recognition. She maintained her Naples workshop while accepting commissions from clients throughout Europe. Her paintings from this period show mature confidence and technical mastery that reflected decades of professional experience.

Her personal life remained complicated. Her husband Pierantonio disappears from historical records around 1623, suggesting their marriage ended through death or separation. She raised her daughter Prudentia alone while managing her business and maintaining relationships with patrons, colleagues, and friends scattered across Europe.

The last documented reference to Artemisia dates from 1654, when she was still accepting new commissions. She probably died during the devastating plague that struck Naples in 1656, though no definitive records survive. She was buried in the church of San Giovanni Battista dei Fiorentini, but her tomb was destroyed when the building was demolished in the 1950s.

Artemisia’s immediate artistic legacy was significant but complicated. Her technical innovations influenced other painters, particularly in her approach to painting fabric and rendering dramatic lighting. Her business methods provided models for other women entering the art profession. However, her reputation was overshadowed for centuries by sensational accounts of her personal life that emphasized scandal over achievement.

Rediscovering Artemisia in the Modern Era

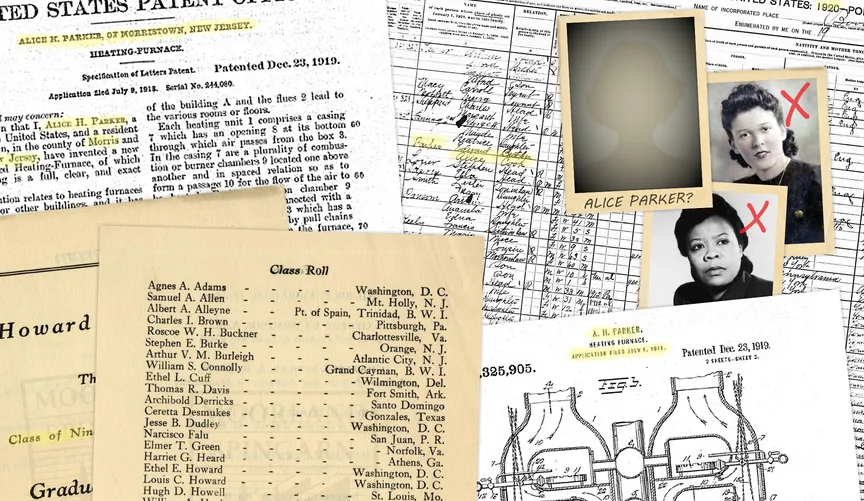

For nearly 300 years after her death, Artemisia Gentileschi was remembered primarily as a victim rather than an artist. Art historians mentioned her as a curiosity, focusing on her rape trial rather than her paintings. When her works were discussed, they were often attributed to her father or other male artists, reflecting assumptions that women couldn’t produce art of such quality.

This situation began changing in the 1970s when feminist scholars started reexamining overlooked women artists. Art historian Linda Nochlin’s influential essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” sparked new interest in recovering women’s contributions to art history. Artemisia became a symbol of female artistic achievement that had been systematically ignored or minimized.

However, early feminist interpretations sometimes created new problems by overemphasizing the connection between Artemisia’s personal trauma and her artistic subjects. Scholars argued that her paintings of strong women reflected her own experiences of male violence, reducing complex works of art to autobiographical documents. This approach, while well-intentioned, limited understanding of her broader artistic development and professional strategies.

More recent scholarship has moved beyond both the sensationalist focus on scandal and the reductive emphasis on personal trauma. Contemporary art historians examine Artemisia’s work within the broader context of Baroque art, comparing her technical methods with those of her male contemporaries and analyzing her business practices alongside other successful artists of her era.

This more sophisticated approach reveals an artist whose achievements were remarkable by any standard. Her technical mastery equaled that of any painter of her generation. Her psychological insight into character and emotion surpassed most of her contemporaries. Her business success demonstrated capabilities that extended far beyond artistic talent into entrepreneurship, marketing, and strategic planning.

The Feminist Significance of Artistic Achievement

From a feminist perspective, Artemisia Gentileschi’s story illustrates both the obstacles women faced in pursuing artistic careers and the extraordinary achievements possible despite those barriers. She succeeded in a profession that systematically excluded women, building an international reputation through talent, determination, and strategic thinking.

Her approach to painting women was revolutionary for its time and remains influential today. Rather than depicting women as decorative objects or symbolic figures, she painted them as complex individuals with their own motivations and capabilities. Her biblical heroines think before they act, showing intelligence as well as courage. Her portraits capture personality as well as physical appearance.

This approach challenged fundamental assumptions about women’s nature and capabilities. By showing women as strong, intelligent, and decisive, Artemisia’s paintings suggested that such qualities were natural rather than exceptional. Her success as an artist demonstrated that women could excel in demanding professional fields when given opportunities.

Her business practices also provided models for other women seeking economic independence. She showed how to negotiate with powerful clients, manage complex projects, and build professional networks. Her correspondence reveals someone who understood money, contracts, and market dynamics as well as any male entrepreneur of her era.

The international scope of her career was particularly significant. She worked successfully in Rome, Florence, Venice, Naples, and London, adapting to different cultural contexts while maintaining her artistic identity. This mobility and adaptability challenged assumptions about women’s supposed need for male protection and domestic stability.

Technical Mastery and Artistic Innovation

Beyond its feminist significance, Artemisia’s work deserves recognition for its purely artistic merits. Her technical skills were exceptional by any standard. She could paint flesh that seemed to glow with inner life, fabric that appeared to have weight and texture, and metal objects that reflected light convincingly. Her understanding of human anatomy was thorough and accurate, allowing her to paint figures in complex poses with complete confidence.

Her use of color was particularly sophisticated. She understood how different pigments interacted with each other and with various lighting conditions. Her paintings maintain their visual impact even after centuries of aging and exposure, testament to her knowledge of materials and techniques. She could work in the dark, dramatic style associated with Caravaggio or the lighter, more colorful approach preferred by Venetian masters.

Her compositional skills showed equal sophistication. She could organize complex multi-figure scenes so that each element contributed to the overall narrative while maintaining visual balance and clarity. Her single-figure paintings demonstrate understanding of how pose, gesture, and facial expression work together to convey character and emotion.

Perhaps most importantly, she developed a distinctive artistic voice that remained recognizable across different periods and styles. Her paintings have a psychological intensity and emotional directness that distinguish them from the work of her contemporaries. She could make viewers feel the weight of a sword, the texture of silk, and the determination in a woman’s eyes with equal conviction.

The Business of Being Artemisia

Artemisia’s success as an artist was inseparable from her skills as a businesswoman. She understood that artistic talent alone wasn’t sufficient for career success; she needed to market herself effectively, maintain client relationships, and manage financial resources carefully. Her approach to these challenges was both innovative and practical.

She developed a personal brand before the concept existed, creating paintings that were immediately identifiable as her work. Clients who commissioned an Artemisia Gentileschi painting knew they would receive something distinctive rather than a generic example of current fashion. This brand identity allowed her to charge premium prices and maintain steady demand for her work.

Her pricing strategy showed sophisticated understanding of market dynamics. She charged more for original compositions than for copies of existing works. She adjusted prices based on painting size, complexity, and deadline pressure. She offered different price points for different types of clients, maximizing revenue while maintaining access to various market segments.

Her client management skills were equally impressive. She maintained correspondence with patrons across Europe, providing updates on work progress and managing expectations about delivery dates. She handled difficult clients diplomatically while protecting her own interests. Her letters show someone who could be both accommodating and firm depending on the situation.

She also understood the importance of professional networks. She maintained relationships with other artists, sharing information about potential commissions and collaborating on major projects. She cultivated friendships with collectors, dealers, and cultural figures who could provide referrals and recommendations. These networks were crucial for maintaining career momentum across multiple cities and countries.

The Revolution Hidden in Plain Sight

What makes Artemisia Gentileschi revolutionary isn’t just that she succeeded as a female artist in a male-dominated field—it’s how she succeeded. She didn’t try to paint like men or hide her female perspective. Instead, she used her unique viewpoint to create works that challenged how everyone saw biblical and mythological stories.

Her technical innovations were equally important. She pioneered techniques in chiaroscuro (the dramatic interplay of light and dark) that influenced generations of artists. Her use of color, particularly in depicting fabric and flesh, set new standards for naturalism. Her compositions, with their dynamic diagonals and psychological intensity, pushed Baroque style in new directions.

More subtly, she changed how artists thought about their subjects’ interior lives. Her women aren’t just beautiful objects or symbols—they’re complex individuals with their own thoughts, desires, and agency. This psychological realism was revolutionary in an era when women in art were typically reduced to types: virgin, mother, whore, or saint.

Her influence extends far beyond the art world. Modern discussions about trauma, survival, and feminine strength owe much to the visual vocabulary Artemisia created. When contemporary artists depict women taking control of their own narratives, they’re building on foundations she laid 400 years ago.

Living Artemisia’s Legacy

Today, Artemisia Gentileschi stands as more than just a great artist—she’s become a symbol of women’s creative power and resilience. But reducing her to a symbol risks losing sight of her specific achievements. She wasn’t great “for a woman”—she was one of the greatest artists of the Baroque period, full stop.

Her technical mastery alone would secure her place in art history. Her “Judith and her Maidservant” (1625) demonstrates an understanding of light, composition, and human anatomy that few artists of any era have matched. Her self-portraits reveal psychological depths that anticipate modern concepts of identity and self-representation. Her religious paintings bring emotional truth to biblical narratives that had become stale through repetition.

But perhaps her greatest achievement was survival itself. In an era when a woman’s rape could destroy not just her reputation but her entire family’s standing, she rebuilt her life and career. She turned the trial that was meant to shame her into the foundation of an international reputation. She refused to let others’ crimes define her possibilities.

Every woman who picks up a paintbrush, a pen, a camera, or any creative tool owes something to Artemisia Gentileschi. Not because she was the first woman artist—she wasn’t—but because she insisted on being seen as an artist who happened to be a woman. She demanded to be judged by her work, not her gender or her trauma.

Her paintings hang in the world’s greatest museums, commanding the attention and respect denied to her during her lifetime. But more importantly, her example hangs in the air every time a woman refuses to accept that certain spaces aren’t for her, every time trauma is transformed into power, every time someone insists on being seen for who they truly are rather than who others expect them to be.

Artemisia Gentileschi didn’t just paint pictures—she painted possibilities. In every brushstroke that refused to apologize for female strength, in every composition that centered women’s experiences, in every signature that proclaimed her authorship in a world that wanted to erase it, she expanded what women could be and do. Her revolution continues every time someone looks at her work and sees not a victim who painted, but a genius who survived.