Contents

ToggleBina Das walked into the University of Calcutta’s Convocation Hall on February 6, 1932, with a loaded revolver and no plan beyond pulling the trigger. She was twenty years old, dressed in the traditional white sari of a Bengali student, and absolutely certain she would die that day.

What happened in the next sixty seconds would make her one of the most famous women in India. But what happened in the sixty years that followed reveals a more complex story about the price of revolutionary fame and the challenges faced by women who dared to challenge empires.

The Making of a Revolutionary Mind

Bina Das was born on August 24, 1911, in Krishnanagar, a small town in Bengal that had become a hotbed of nationalist sentiment. Her father, Benoy Bhushan Das, was a teacher and social reformer who believed education could liberate India from British rule. Her mother, Sarala Devi, came from a family of writers and activists who had been questioning British authority since the 1890s.

This wasn’t a household where revolution was discussed in whispers. Political resistance was the family business. Bina grew up listening to stories about Khudiram Bose, who had been hanged by the British at eighteen for bombing a carriage he thought contained a British magistrate. She heard detailed accounts of the Swadeshi movement and the partition of Bengal that had torn her region apart in 1905.

By the time Bina reached adolescence, Bengal was experiencing what historians call the “revolutionary phase” of the independence movement. Young men and women were joining secret societies dedicated to armed resistance against British rule. Unlike the non-violent civil disobedience promoted by Gandhi, these groups believed violence was the only language the British understood and to some extent, rightly so.

The intellectual environment that shaped Bina’s worldview was unique to Bengal in the early twentieth century. The region had produced a generation of educated Indians who read Marxist literature, studied Russian revolutionary tactics, and debated European anarchist philosophy. They saw themselves as part of a global struggle against imperialism and capitalism.

But there was something distinctly Bengali about their approach to revolution. They combined Western political theory with Hindu concepts of duty and sacrifice. Many revolutionaries saw their actions as expressions of dharma—righteous duty that transcended personal safety or conventional morality. This spiritual dimension of political resistance would profoundly influence how Bina understood her own mission.

When Bina enrolled at Bethune College in Calcutta in 1929, she entered an environment where revolutionary ideas were openly discussed despite British surveillance. The college had been founded to equip Bengali women with modern education, and many of its graduates had become prominent in social reform movements. The atmosphere encouraged intellectual independence and political awareness that British authorities found deeply threatening.

The Underground Network That Shaped Her

Bina’s transformation from student to revolutionary began when she joined Chhatri Sangha, an organization that most historians have misunderstood or ignored entirely. Usually described as a “semi-revolutionary” women’s group, Chhatri Sangha was actually a sophisticated network that recruited, trained, and deployed female operatives for the anti-British underground.

The organization was founded by Kalpana Datta, a chemistry student who had been involved in the famous Chittagong Armoury Raid of 1930. Unlike male revolutionary groups that treated women as supporters or messengers, Chhatri Sangha trained women for direct action. Members learned to handle firearms, make explosives, and plan operations with the same rigor as their male counterparts.

This training wasn’t theoretical. By 1931, several Chhatri Sangha members had participated in bombings, assassinations, and armed robberies designed to fund revolutionary activities. The British intelligence reports from this period, which remained classified for decades after independence, reveal that colonial authorities considered the women’s revolutionary groups to be among the most dangerous threats to their rule.

What made these women particularly dangerous was their ability to move through society without suspicion. A young woman in a white sari could attend public meetings, visit government offices, and gather intelligence in ways that were impossible for men who were already under surveillance. British officials struggled to adapt their security procedures to account for threats that came from sources they had previously considered harmless.

Bina’s recruitment into this network wasn’t accidental. Her family background, educational record, and psychological profile made her an ideal candidate for revolutionary work. Intelligence reports suggest that Chhatri Sangha had been monitoring her since her enrollment at Bethune College, waiting for the right moment to approach her with an invitation to join their cause.

The process of radicalization was gradual but systematic. New members were introduced to revolutionary literature and required to attend discussion groups where they analyzed the moral and practical justifications for political violence. They studied the biographies of successful revolutionaries from around the world and debated the tactical advantages of different approaches to resistance.

Most importantly, they were taught to think of themselves as soldiers in a war rather than criminals committing isolated acts of violence. This military framework provided psychological preparation for operations that would have been unthinkable for young women from respectable families under normal circumstances.

The Day That Changed Everything

The University of Calcutta’s Convocation Hall was packed with British officials, Indian administrators, and prominent citizens on February 6, 1932. Governor Stanley Jackson was scheduled to address the graduating class and present degrees to students who had completed their studies. It was exactly the kind of ceremonial event that the colonial government used to display its authority and legitimacy.

What the audience didn’t know was that three separate revolutionary groups had identified this event as a target for assassination attempts. The British intelligence services, despite their extensive surveillance networks, had failed to detect any of these plots. The security arrangements were designed to prevent disruptions from protesters, not armed attacks from within the audience.

Bina arrived at the venue early, wearing a white cotton sari that was standard dress for Bengali college students. She carried a small handbag that contained a .32 caliber revolver provided by Kamala Das Gupta, another Chhatri Sangha member who had acquired the weapon from revolutionary contacts in Chittagong. The gun had been tested the previous week to ensure it was functional.

Her seat was in the section reserved for female students, about thirty feet from the stage where Governor Jackson would be speaking. This positioning was crucial because it placed her within effective range of the revolver while keeping her in an area where security guards were unlikely to expect trouble.

The psychological preparation for this moment had been extensive. Bina had written what she expected would be her final letter to her parents, explaining her decision to sacrifice her life for India’s freedom. She had also prepared a detailed confession that outlined her political beliefs and motivations. Both documents revealed a young woman who had thought deeply about the philosophical implications of political violence.

When Governor Jackson rose to address the audience, Bina stood up and fired five shots in rapid succession. The acoustics of the hall amplified the gunshots, creating chaos as people screamed and dove for cover. Security personnel initially couldn’t identify the source of the shots because they had assumed any threat would come from the male section of the audience.

None of the bullets hit Governor Jackson, though several came close enough to tear holes in his ceremonial robes. British officials later claimed this was evidence of poor marksmanship, but ballistics analysis suggested that Bina had deliberately aimed to miss. Her goal was not assassination but martyrdom – a public demonstration of resistance that would inspire others to join the revolutionary cause.

The Trial That Made Her Famous

Bina made no attempt to escape after firing the shots. She stood calmly as security guards disarmed her and placed her under arrest. Her behavior during the arrest impressed even British observers, who noted her composure and dignity under extremely stressful circumstances.

The confession she had prepared became one of the most widely circulated documents in the history of the Indian independence movement. Despite British attempts at censorship, copies were distributed throughout Bengal and eventually reached nationalist newspapers across India. The document revealed a sophisticated understanding of political theory and moral philosophy that surprised officials who had expected the typical rhetoric of youthful rebellion.

In her confession, Bina wrote: “My object was to die, and if to die, to die nobly fighting against this despotic system of Government, which has kept my country in perpetual subjection to its infinite shame and endless suffering.” This statement captured the spiritual dimension of her revolutionary commitment in language that resonated with Indians across religious and cultural boundaries.

The British authorities faced a difficult decision about how to prosecute her case. Executing a twenty-year-old female student would create a martyr and potentially trigger widespread unrest. But showing leniency might encourage copycat attacks from other young revolutionaries. They settled on a sentence of nine years of rigorous imprisonment, hoping to remove her from public attention while avoiding the political costs of execution.

The trial itself became a platform for Bina to articulate a sophisticated critique of British rule that went far beyond simple nationalism. She argued that colonialism was fundamentally incompatible with human dignity and that violent resistance was morally justified when peaceful methods had failed. Her courtroom speeches were reported in newspapers throughout India and inspired a new generation of revolutionary activists.

British intelligence reports from this period reveal official concern about the impact of her trial on public opinion. Colonial authorities had successfully suppressed news coverage of many revolutionary activities, but Bina’s case attracted too much attention to be hidden. Her youth, gender, and articulate presentation of her beliefs made her an ideal symbol for anti-British sentiment.

The sentence of rigorous imprisonment was designed to break her spirit through harsh physical conditions and psychological isolation. British prisons in India were notorious for their brutal treatment of political prisoners, and officials expected that nine years of such treatment would transform the defiant young revolutionary into a broken woman willing to renounce her beliefs in exchange for early release.

The Prison Years That Forged Her Character

Presidency Jail in Calcutta, where Bina served most of her sentence, was designed to crush the spirits of political prisoners through systematic dehumanization. Cells were small, poorly ventilated, and infested with rats and insects. Food was deliberately inadequate in both quantity and quality. Prisoners were forbidden to speak to each other and were punished severely for any violation of rules.

HerWiki is built and maintained by the support of amazing readers like you. If this story inspired you, join the cause and help us make HerWiki bigger and better.

Bina’s experience in prison was particularly harsh because British authorities were determined to make an example of her. She was placed in solitary confinement for extended periods and denied access to books, newspapers, or correspondence with family members. The goal was to break her psychologically and force her to publicly renounce her revolutionary beliefs.

Instead of breaking her spirit, the prison experience deepened her political convictions and broadened her intellectual horizons. She used the enforced isolation to reflect on the philosophical foundations of her beliefs and to develop a more sophisticated understanding of the relationship between individual action and social change.

During her imprisonment, she managed to maintain contact with other political prisoners through a complex system of coded messages passed through sympathetic guards and prison staff. This underground communication network allowed revolutionary leaders to coordinate their activities even while incarcerated and helped maintain morale among prisoners facing long sentences.

The harsh conditions also gave Bina firsthand experience of the systematic violence that underpinned British rule in India. She witnessed the torture of other prisoners, the deliberate withholding of medical care, and the use of sexual violence as a tool of political intimidation. These experiences convinced her that the colonial system was fundamentally criminal and that violent resistance was not only justified but morally required.

Her health deteriorated significantly during her imprisonment, and she developed respiratory problems that would plague her for the rest of her life. British medical records from the prison, which were not made public until decades after independence, reveal that authorities were aware of her declining health but refused to provide adequate treatment as part of their strategy to break her will.

The psychological impact of prolonged isolation and harsh treatment was severe, but Bina developed coping strategies that allowed her to maintain her sanity and political commitment. She created elaborate mental exercises to occupy her mind, composed poetry that she memorized rather than writing down, and developed a meditation practice that drew on both Hindu spiritual traditions and Western philosophical techniques.

Returning to a Completely Different World

When Bina was released from prison in 1939, she found an independence movement that had been transformed by nearly a decade of political developments. Gandhi’s strategy of non-violent civil disobedience had gained international attention and support, while the revolutionary movement that had inspired her initial activism had been largely crushed by British repression.

The world outside prison had also changed dramatically. The global economic depression had created new forms of political instability, and the rise of fascism in Europe was forcing Indian intellectuals to reconsider their assumptions about violence, democracy, and social change. Many former revolutionaries were questioning whether armed resistance was still relevant in this new political environment.

Bina’s reintegration into political life was complicated by her celebrity status as a revolutionary hero. Younger activists viewed her with a mixture of admiration and curiosity, while older political leaders were uncertain about how to incorporate someone with her radical background into mainstream independence activities. They also felt threatened by her stature because that could very easily interfere with their own limelight. Her prison experience had given her moral authority, but it had also isolated her from the practical work of political organizing.

She joined the Indian National Congress, the umbrella organization leading the independence movement, but struggled to find a meaningful role within its hierarchical structure. Congress leaders respected her sacrifices but were uncomfortable with her continued advocacy for revolutionary methods. They preferred to use her as a symbol of resistance rather than as an active participant in strategic decision-making.

The outbreak of World War II created new opportunities for anti-British activism, and Bina threw herself into the Quit India Movement launched by Gandhi in 1942. This campaign called for immediate independence and organized massive civil disobedience to pressure the British government to withdraw from India. For Bina, it represented a chance to continue her revolutionary work through legal political channels.

Her participation in Quit India activities led to her arrest and imprisonment for an additional three years, from 1942 to 1945. This second period of incarceration was less harsh than her first, partly because British authorities were focused on the war effort and partly because her advanced age and poor health made her less threatening in their eyes.

The Complex Legacy of Independence

India’s independence in 1947 should have been the culmination of Bina’s life work, but the reality proved more complicated than she had anticipated. The partition of India into separate Hindu and Muslim nations created massive refugee crises and communal violence that challenged her assumptions about nationalism and social progress.

Her marriage to Jatish Chandra Bhaumik, a fellow revolutionary from the Jugantar group, represented both personal fulfillment and political compromise. Bhaumik had also spent years in British prisons for his anti-colonial activities, and their relationship was based on shared experiences of sacrifice and struggle. But marriage also meant accepting domestic responsibilities that limited her political activities.

The couple’s political views had evolved in different directions during their years of imprisonment and activism. Bina had become increasingly attracted to socialist and communist ideologies that emphasized economic justice and social equality. Bhaumik remained more focused on nationalist goals and was less interested in the class-based analysis that was becoming central to Bina’s worldview.

Her election to the provincial assembly in West Bengal provided an opportunity to translate her revolutionary ideals into practical legislation, but she quickly became frustrated with the compromises and bureaucratic procedures required for effective governance. The slow pace of social change through democratic institutions seemed inadequate to address the massive problems facing newly independent India.

Her decision to leave the Congress Party reflected deeper ideological differences about the direction of post-independence India. Congress leaders were focused on building stable institutions and maintaining national unity, while Bina believed that true liberation required more fundamental economic and social transformations that the party was unwilling to pursue.

Although she never formally joined the Communist Party, Bina was increasingly drawn to Marxist analysis of Indian society and believed that capitalism would prevent the country from achieving genuine independence. She argued that political freedom without economic justice was meaningless for the vast majority of Indians who remained trapped in poverty and exploitation.

The Gradual Fade from Public Memory

The decades following independence saw Bina’s gradual disappearance from public consciousness as India’s political leaders focused on nation-building rather than celebrating revolutionary heroes. The official narrative of independence emphasized Gandhi’s non-violent methods and downplayed the contributions of armed resistance movements that had challenged British rule through force.

This erasure of revolutionary history was deliberate and systematic. The new Indian government wanted to present itself as a responsible member of the international community and was uncomfortable with associations to political violence, even violence directed against colonial oppression. Revolutionary leaders like Bina were honored in ceremonial ways but excluded from meaningful roles in governance or policy-making.

Her poor health, exacerbated by years of imprisonment and harsh treatment, limited her ability to remain active in political movements or to write about her experiences. The respiratory problems she had developed in prison worsened over time, and she struggled with depression and social isolation that made it difficult to maintain the public presence necessary for continued relevance.

The death of her husband in the 1970s left her alone and financially insecure. The pension she received from the government as a freedom fighter was criminally inadequate to cover her basic needs, and she had no children or close relatives who could provide any form of support. Here was a revolutionary woman who had sacrificed her youth for India’s independence but was abandoned in her difficult days while her male adversaries enjoyed at the dime of the citizens of India.

Her move to Rishikesh, the spiritual center in the Himalayan foothills, represented both a search for peace and an acknowledgment of her marginalization from mainstream political life. The town attracted spiritual seekers and political refugees who were looking for alternatives to the materialistic values that seemed to dominate post-independence India.

In Rishikesh, Bina lived quietly and anonymously, supporting herself through small pensions and occasional donations from admirers who recognized her lifelong fight for the country they now called theirs. She spent her time reading, meditating, and writing autobiographical works that would not be published until after her death. These writings revealed a woman who remained committed to her revolutionary ideals despite the excruciating disappointments of her later life.

Setting of the Big, Bright Sun

Bina Das died alone on December 26, 1986, and her body was found on a roadside in Rishikesh in a partially decomposed state. The circumstances of her death reflected the tragic irony of a woman who had once been famous throughout India for fighting tooth and nail for the average Indian’s right to call India home dying in complete anonymity and poverty—because she was a woman and came from a humble background. It took police over a month to identify her remains, and her death received no attention at all in the national media.

Alternative accounts of her death, provided by distant relatives decades later, suggest she may have collapsed at a bus stand and died in a hospital rather than on the roadside. These conflicting narratives make me even angrier. Considering the amount and nature of the sacrifices she made on her journey to India’s freedom and independence, she deserved a lot better than having even the account of her demise not being clear and well documented.

The delayed and very long due recognition of her fight began in the 1990s, when historians and feminists started investigating the role of women in India’s independence movement. Research revealed that hundreds of women had participated in revolutionary activities but had been systematically excluded from historical accounts that focused on male leaders and mainstream political organizations.

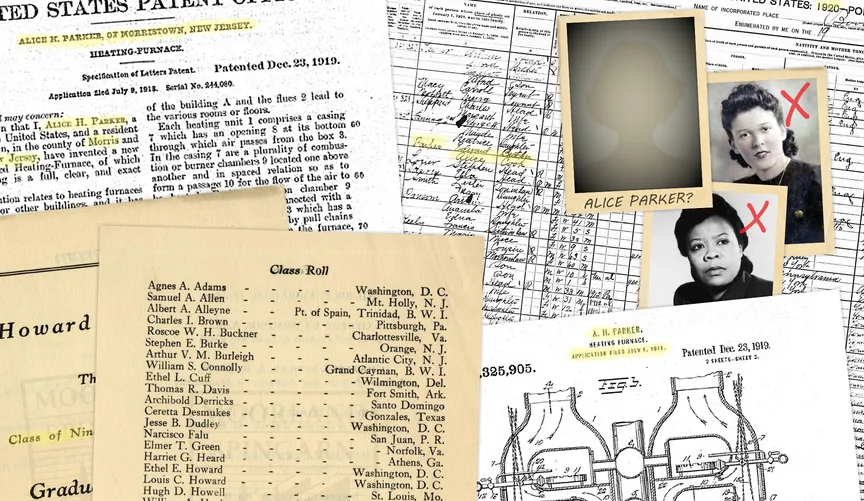

In 2012, the University of Calcutta posthumously awarded graduation certificates to Bina and Pritilata Waddedar, acknowledging that the British authorities had prevented them from completing their education because of their political activities. This gesture, coming eighty years after the fact, represented a symbolic recognition of the price these women had paid for their revolutionary commitments.

Redefining Revolutionary Success

Bina’s unsuccessful assassination attempt was actually more politically effective than a successful killing would have been. By surviving and standing trial, she was able to articulate a sophisticated critique of colonialism that reached audiences throughout India and inspired other young people to join the independence movement. Her martyrdom was symbolic rather than literal, but no less powerful for that distinction.

Her prison experiences provided insights into the systematic violence that underpinned colonial rule and the particular ways that this violence was directed against women political prisoners. Her survival and continued resistance despite harsh treatment demonstrated forms of courage and endurance that were different from but equally significant as the bravery displayed in armed combat.

The intellectual development she demonstrated throughout her career, from impulsive young revolutionary to sophisticated political theorist, illustrated the capacity of women to grow and adapt their understanding of social change despite limited formal education and restricted access to political institutions.

Her later attraction to socialist and communist ideologies reflected a broader evolution in her thinking about the relationship between political independence and social justice. Unlike many male revolutionaries who focused narrowly on anti-colonial nationalism, she understood that true liberation required addressing economic inequality and social oppression that transcended colonial rule.

The Hidden Impact on Indian Feminism

Bina’s story had profound but largely unacknowledged influence on the development of feminist consciousness in twentieth-century India. Her example demonstrated that women could take direct action to challenge oppressive authority rather than relying on men to fight for their liberation. This message was particularly powerful for educated women who were questioning traditional gender roles and seeking new forms of political expression.

The network of women revolutionaries that surrounded her, including organizations like Chhatri Sangha, created alternative models of female solidarity and mutual support that challenged patriarchal assumptions about women’s political capabilities. These networks provided training, resources, and emotional support that enabled individual women to undertake activities that would have been impossible in isolation.

Her articulate presentation of revolutionary ideology in her trial speeches and writings demonstrated women’s intellectual capacity to analyze complex political questions and develop sophisticated theoretical frameworks for understanding social change. This intellectual leadership contradicted stereotypes about women’s political thinking and provided models for later generations of feminist theorists.

The harsh treatment she received in prison for her political activities revealed the particular ways that state violence was directed against women who challenged authority. Her survival and continued resistance despite this treatment provided inspiration for later feminist movements that faced similar forms of repression and intimidation.

Her post-independence political activities, including her decision to leave the Congress Party over ideological differences, demonstrated forms of principled independence that challenged expectations about women’s political loyalty and deference to male leadership. Her willingness to prioritize political principles over party solidarity provided models for later feminist politicians.