Contents

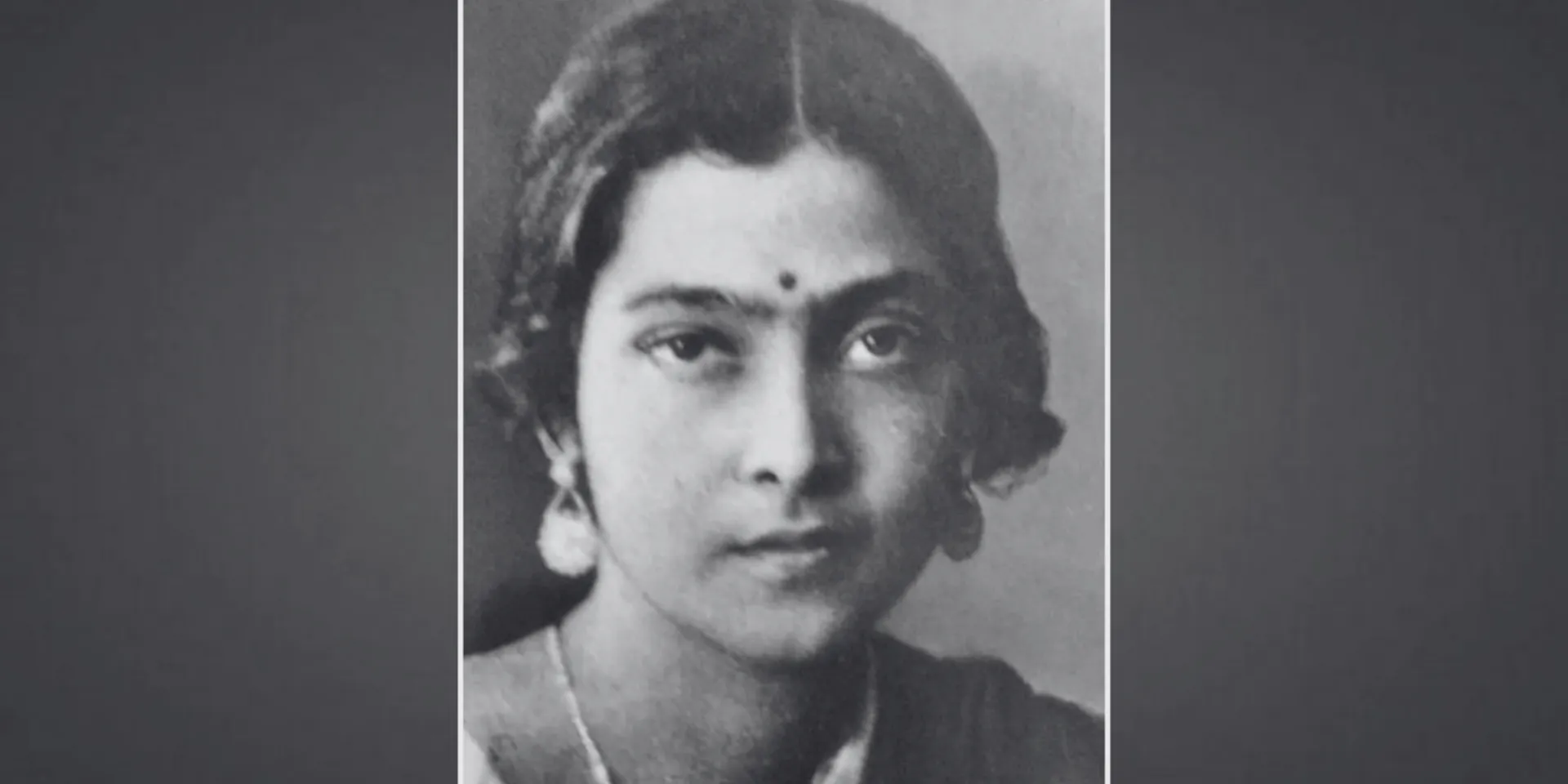

ToggleEvery guitar riff that makes your heart race traces back to a black woman in a church dress. Every rock anthem that moves crowds connects to a gospel singer who refused to stay in her lane. Sister Rosetta Tharpe didn’t just influence rock and roll – she created it. While men get credit for inventing the genre, the truth is simpler and more radical: rock and roll was born from the hands and voice of a queer black woman who plugged her guitar into an amplifier and changed music forever.

The erasure of Tharpe from rock history isn’t accidental. It reflects deeper patterns about whose contributions get remembered and whose get forgotten.

The Roots of Revolution

Rosetta Nubin entered the world on March 20, 1915, in Cotton Plant, Arkansas, a place where cotton fields stretched beyond the horizon and segregation was the law. Her parents, Katie Bell Nubin and Willis Atkins, picked cotton for white landowners who paid barely enough to survive. This wasn’t unusual for black families in the Jim Crow South. What was unusual was the music that filled their home despite the hardship.

Katie Bell wasn’t just a cotton picker. She was a mandolin player, a singer, and a deaconess-missionary for the Church of God in Christ. The COGIC was different from other churches. Founded by Charles Harrison Mason, it encouraged rhythmic musical expression, dancing in praise, and allowed women to sing and teach. In most churches, women were expected to sit quietly. In COGIC, they could lead.

Willis Atkins sang too, though little else is known about him. What mattered was that both parents understood music as power. In a world that tried to silence black voices, they taught their daughter that her voice could move people, change minds, and open doors that seemed permanently locked.

The family’s poverty was real and grinding. Cotton picking paid pennies, and black families faced constant threats of violence from white supremacists who controlled every aspect of southern life. But inside their home, music created a different reality. Six-year-old Rosetta learned guitar alongside her letters and numbers. Her mother recognized something extraordinary in the child’s musical ability and began planning how to use it.

This early recognition of talent wasn’t accidental. Black families in the South understood that exceptional ability could provide escape routes from systems designed to keep them trapped. Music, athletics, and entertainment offered some of the few paths through which black people could achieve economic security and social recognition. Katie Bell saw her daughter’s gift and made a calculated decision to build a career around it.

The Making of a Prodigy

In 1921, six-year-old Rosetta joined her mother as a regular performer in a traveling evangelical troupe. Billed as a “singing and guitar playing miracle,” she accompanied Katie Bell in performances that blended sermon and concert before audiences across the American South. This wasn’t child exploitation – it was a survival strategy in a system that offered black families few options for advancement.

The traveling church circuit was a world unto itself. Preachers, musicians, and performers moved from town to town, creating temporary communities in churches, tent revivals, and community centers. For black performers, it provided opportunities to develop skills, build audiences, and earn money in ways that the segregated mainstream entertainment industry didn’t allow.

Rosetta’s performances during this period were remarkable for several reasons. First, she was a female guitarist at a time when guitar playing was considered a masculine skill. Second, she was a black performer commanding white and black audiences in the segregated South. Third, she was developing a musical style that blended gospel, blues, and folk in ways that nobody had heard before.

The guitar work she developed during these early years would later revolutionize popular music. She combined the rhythmic drive of blues with the spiritual intensity of gospel and the technical precision of folk fingerpicking. Her right hand attacked the strings with percussive force while her left hand created melodic lines that soared above the rhythm. This combination of aggression and beauty would become the foundation of rock guitar playing.

But her vocal style was equally innovative. She could deliver a traditional gospel song with the power and emotion that church audiences expected, then shift into a blues-inflected approach that added sexual tension and personal vulnerability to spiritual lyrics. This vocal flexibility allowed her to communicate with different audiences while maintaining her artistic authenticity.

The traveling years also taught her stage presence and audience management. By age 10, she could command a room full of adults through sheer force of personality. She learned to read crowds, adjust her performance to their energy, and create the kind of collective experience that made people remember her long after she moved on to the next town.

Chicago and the Big Time

Around 1925, Rosetta and Katie Bell settled in Chicago, where they performed religious concerts at Roberts Temple COGIC on 40th Street. Chicago in the 1920s was the center of black cultural life in America. The Great Migration had brought hundreds of thousands of black southerners to the city, creating a concentrated market for black entertainment and culture.

Chicago offered opportunities that small southern towns couldn’t provide. Recording studios, radio stations, nightclubs, and theaters created an entertainment ecosystem where talented performers could build careers. But it also presented challenges. Competition was fierce, audiences were sophisticated, and the music business was controlled by white executives who often exploited black performers.

For a teenage girl from rural Arkansas, Chicago represented both opportunity and danger. The city’s South Side was home to blues clubs, jazz venues, and entertainment districts where sexual and musical boundaries were constantly tested. Rosetta was developing into a young woman in an environment where female performers faced constant pressure to compromise their artistic integrity for commercial success.

But she also encountered musical influences that expanded her artistic vision. Chicago blues was developing its distinctive electric sound during this period. Jazz musicians were experimenting with new harmonic concepts and rhythmic approaches. Gospel music was evolving beyond traditional hymns toward more contemporary expressions. Rosetta absorbed all of these influences while maintaining her connection to the spiritual roots of her music.

Her reputation as a musical prodigy grew throughout the Chicago church community. She was already standing out in an era when prominent black female guitarists were extremely rare. Most women musicians played piano or sang. Guitar was considered a man’s instrument, especially in blues and secular contexts. Rosetta’s mastery of the instrument marked her as exceptional from the beginning.

The Chicago years also deepened her understanding of music as a business. She watched how successful performers managed their careers, built audiences, and negotiated with venue owners and promoters. This education would prove crucial when she moved into the mainstream entertainment industry and faced much more complex commercial challenges.

Marriage, Name, and Identity

In 1934, 19-year-old Rosetta married Thomas Thorpe, a COGIC preacher who accompanied her and Katie Bell on many of their tours. The marriage was brief, lasting only a few years, but it provided her with the stage name that would define her career: Sister Rosetta Tharpe. The decision to adopt a version of her husband’s surname as her professional identity was both practical and symbolic.

The “Sister” title reflected her position within the COGIC church hierarchy and signaled to audiences that she remained connected to her spiritual roots despite performing in secular venues. This religious identification would become crucial as her career developed and she faced criticism from conservative church members who disapproved of her crossover into popular music.

But the marriage also represented the complex negotiations that women performers had to make in the 1930s. Marriage provided social respectability and could offer protection from the sexual harassment that female entertainers routinely faced. At the same time, it could limit artistic freedom and career opportunities. Many women performers had to choose between marriage and professional success.

Tharpe’s marriage to a preacher was particularly strategic because it maintained her credibility within the church community while providing some protection as she ventured into secular entertainment. Thomas Thorpe’s presence on tours served as a form of chaperoning that made it easier for venues to book her and for audiences to accept her.

The brevity of the marriage suggests that Tharpe prioritized her career over domestic expectations. In 1938, she left Thomas and moved with her mother to New York City, pursuing opportunities that marriage to a traveling preacher couldn’t provide. This decision required considerable courage given the limited options available to divorced women in the 1930s.

The move to New York represented a fundamental shift in her career trajectory. Chicago had provided training and early success within the black entertainment community. New York offered access to the mainstream recording industry, national radio networks, and integrated venues where black performers could reach white audiences. But it also meant competing in an environment where racial and gender discrimination was institutionalized and often violent.

Breaking Into the Mainstream

On October 31, 1938, 23-year-old Tharpe walked into Decca Records’ New York studio and recorded four songs that would change popular music forever. “Rock Me,” “That’s All,” “My Man and I,” and “The Lonesome Road” were the first gospel songs recorded by Decca and became instant hits, establishing Tharpe as an overnight sensation.

The significance of this recording session extends far beyond commercial success. Decca was a major label that typically recorded white pop singers and big band leaders. By signing Tharpe and marketing her records to both black and white audiences, the label acknowledged that gospel music had crossover potential that nobody had previously recognized.

“Rock Me” was particularly revolutionary. The song combined traditional gospel lyrics with a rhythmic drive and guitar style that anticipated rock and roll by more than a decade. Tharpe’s vocal delivery was simultaneously spiritual and sensual, creating a tension that made listeners pay attention in new ways. The guitar work featured distorted single-note lines and rhythmic chord patterns that would become standard elements of rock music.

The immediate success of these recordings created opportunities and problems that Tharpe would navigate for the rest of her career. White audiences loved the exotic appeal of black gospel music performed with unprecedented musical sophistication. Black church audiences appreciated seeing one of their own achieve mainstream recognition. But conservative church members worried that she was compromising sacred music for commercial gain.

The recording success led to appearances with major entertainment figures who recognized her talent and commercial potential. Cab Calloway invited her to perform at Harlem’s Cotton Club in October 1938. John Hammond included her in his “Spirituals to Swing” concert at Carnegie Hall on December 23, 1938. These appearances exposed her to new audiences and established her as a major entertainment figure.

HerWiki is built and maintained by the support of amazing readers like you. If this story inspired you, join the cause and help us make HerWiki bigger and better.

But they also intensified criticism from church members who felt that performing in nightclubs and alongside secular entertainers violated the sacred nature of gospel music. The Cotton Club was particularly controversial because it was owned by white gangsters and featured scantily clad dancers performing for predominantly white audiences. For a gospel singer to appear in such a venue challenged fundamental assumptions about the boundaries between sacred and secular entertainment.

The Electric Guitar Revolution

While Tharpe’s vocal abilities earned critical acclaim, her guitar innovations were creating a musical revolution that would transform popular culture. In the late 1930s, most guitarists played acoustic instruments that were barely audible when performing with bands or in large venues. Electric guitars existed but were primarily used by jazz musicians playing clean, undistorted tones.

Tharpe began experimenting with electric guitar amplification and distortion effects that created an entirely new sonic palette. She discovered that overdriving her amplifier produced a warm, sustaining distortion that made her guitar lines cut through any musical arrangement. This wasn’t accidental noise – it was a deliberate artistic choice that added emotional intensity to her playing.

Her approach to electric guitar was revolutionary in several ways. She used the instrument’s volume and sustain capabilities to create melodic lines that functioned like a second lead vocal. She developed rhythmic techniques that combined blues-style single notes with gospel-influenced chord patterns. Most importantly, she understood how distortion could add emotional expression to musical phrases.

The technical aspects of her guitar innovations were sophisticated. She experimented with different pickup positions, amplifier settings, and playing techniques to achieve specific tonal results. She developed a right-hand attack that combined pick playing with fingerstyle techniques, creating dynamic variety that kept listeners engaged. Her left-hand work included bending techniques, vibrato, and melodic patterns that influenced generations of rock guitarists.

But the cultural significance of her electric guitar work extends beyond technical innovation. By demonstrating that women could master electric instruments and use them for aggressive, powerful musical expression, she challenged assumptions about gender roles that limited women’s participation in popular music. Her success proved that women could be just as compelling as men when given access to the same tools and opportunities.

The influence of her guitar style on later rock musicians is direct and documented. Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, and countless others borrowed specific techniques, rhythmic patterns, and sonic approaches that Tharpe had developed. But because rock history has been written primarily by white male critics, her foundational contributions have been minimized or ignored entirely.

Navigating Controversy and Compromise

Tharpe’s decision to perform in nightclubs while maintaining her identity as a gospel singer created ongoing tensions that shaped her entire career. Conservative church members accused her of selling out sacred music for commercial gain. Secular audiences sometimes viewed her religious identity as limiting her artistic authenticity. She had to constantly navigate between these competing expectations while maintaining her artistic integrity.

The criticism from church communities was particularly painful because it came from people who had supported her early career and shared her spiritual values. Many COGIC members felt that gospel music belonged exclusively in religious contexts and that performing it in nightclubs or alongside secular entertainers violated its sacred nature. Some churches banned her records or refused to let her perform at church events.

But Tharpe understood something that her critics missed: music could be sacred regardless of where it was performed. She believed that spreading gospel music to secular audiences served a missionary purpose that justified the controversy it created. Her performances in nightclubs introduced gospel music to people who would never enter a church but might be moved by its spiritual message.

The tension between sacred and secular contexts also created artistic opportunities that purely religious performers couldn’t access. By performing for diverse audiences, she learned to communicate with people from different cultural backgrounds and musical preferences. This versatility made her a more complete artist and expanded the emotional range of her performances.

Her contractual obligations sometimes forced compromises that conflicted with her artistic preferences. In 1943, she considered rebuilding a strictly gospel act but was contractually required to perform more worldly material. These business pressures illustrated how women performers, particularly black women, often had limited control over their artistic careers despite their talent and commercial success.

The financial realities of the music business also influenced her artistic choices. Gospel music alone couldn’t provide the income needed to support herself, her mother, and later her own family. Crossover success offered economic security that purely religious music couldn’t match. But achieving that success required artistic compromises that created ongoing internal conflicts.

Wartime Success and Innovation

During World War II, Tharpe became one of only two gospel artists authorized to record V-discs for American troops overseas. This recognition from the U.S. military validated her importance as a cultural figure while demonstrating gospel music’s power to provide comfort and inspiration during wartime.

Her 1944 recording of “Strange Things Happening Every Day” with pianist Sammy Price became the first gospel song to appear on Billboard’s Harlem Hit Parade, reaching number 2 on what was then called the “race records” chart. The song’s commercial success proved that gospel music could compete in the mainstream market when presented with sufficient musical sophistication and marketing support.

But “Strange Things Happening Every Day” was significant for reasons beyond commercial success. Many music historians consider it the first rock and roll record because it combined gospel lyrics with a rhythmic drive, guitar style, and overall energy that directly anticipated the rock music of the 1950s. If this assessment is correct, then rock and roll was invented by a black woman performing gospel music, not by the white male musicians who typically receive credit for the genre’s creation.

The song’s lyrics addressed the social upheavals of wartime while maintaining their spiritual message. Tharpe sang about strange events and changing times with an urgency that reflected the uncertainty many people felt during the war. But she also conveyed faith that these difficulties would ultimately lead to positive change. This combination of social commentary and spiritual hope became a defining characteristic of rock music.

Her guitar work on the recording featured distorted single-note lines, rhythmic chord patterns, and an overall energy level that was unprecedented in popular music. The production techniques used on the session, including the balance between voice and guitar and the overall sonic approach, became templates for rock recordings. When rock and roll exploded in the 1950s, many of its defining characteristics had already been established by Tharpe more than a decade earlier.

The wartime period also saw Tharpe developing the stage presence and performance techniques that would influence rock entertainers for generations. She learned to use her guitar as a visual prop, incorporating dramatic gestures and dance movements that enhanced the music’s emotional impact. Her ability to command large audiences through sheer force of personality became a model for later rock performers.

Personal Relationships and Hidden Lives

In 1946, Tharpe attended a Mahalia Jackson concert in New York and discovered Marie Knight, a young gospel singer whose talent and beauty immediately captivated her. Two weeks later, Tharpe appeared at Knight’s doorstep with an invitation to go on the road together. This meeting began both a professional partnership and a romantic relationship that would define Tharpe’s personal life for several years.

The relationship between Tharpe and Knight was carefully hidden from public view because homosexuality was illegal and socially unacceptable in the 1940s. For black women in the entertainment industry, any hint of sexual nonconformity could destroy careers and personal safety. But according to Tharpe’s biographer Gayle Wald, the two women became lovers as well as musical partners.

Their professional collaboration produced some of gospel music’s most memorable recordings, including “Up Above My Head” and “Gospel Train.” Knight’s soprano voice complemented Tharpe’s alto perfectly, creating harmonies that added new dimensions to traditional gospel arrangements. Their stage chemistry was undeniable, but audiences interpreted it as spiritual sisterhood rather than romantic connection.

The hidden nature of their relationship reflects the broader invisibility of LGBTQ+ people in 1940s America, particularly within black communities where respectability politics demanded conformity to heterosexual norms. Gospel music was especially conservative regarding sexuality, making it impossible for performers to openly acknowledge same-sex relationships without facing career destruction.

But the relationship also provided Tharpe with emotional support and artistic inspiration during the most successful period of her career. Knight understood the pressures of being a female performer in a male-dominated industry and shared Tharpe’s commitment to musical excellence. Their partnership allowed both women to develop artistically in ways that solo careers might not have permitted.

The secrecy required to maintain their relationship took an emotional toll that became apparent as their professional partnership developed. They had to present themselves as platonic friends while managing the complications of being romantic partners who traveled together, shared hotel rooms, and performed intimate duets in front of audiences who couldn’t know the truth about their connection.

The Decline and Separation

By 1949, the professional and personal relationship between Tharpe and Knight was deteriorating under multiple pressures. Mahalia Jackson was beginning to eclipse Tharpe in popularity among gospel audiences. Knight harbored desires to break into popular music as a solo performer. Most tragically, Knight lost her children and mother in a house fire that devastated her emotionally and created distance between the two women.

The fire represents one of those random tragedies that change life trajectories in unpredictable ways. Knight’s grief and guilt over her family’s deaths made it difficult for her to maintain the emotional intimacy that had sustained her relationship with Tharpe. The shared professional goals that had brought them together began to seem less important than Knight’s need to rebuild her personal life.

Tharpe’s response to the deteriorating relationship was to increase her public profile through spectacular promotional events. In 1951, she attracted 25,000 paying customers to her wedding to manager Russell Morrison at Griffith Stadium in Washington, D.C. The wedding was followed by a vocal performance that turned the ceremony into a concert event.

The public wedding served multiple purposes. It provided spectacular publicity that reinforced her career during a period when her popularity was declining. It also functioned as a declaration of heterosexual respectability that deflected any speculation about her relationship with Knight or her sexual orientation generally. The choice of a baseball stadium as the venue emphasized the entertainment rather than sacred aspects of the ceremony.

But the wedding also represented a form of public performance that required Tharpe to present a version of herself that contradicted her private reality. The gap between her public heterosexual persona and her actual romantic preferences created psychological pressures that would affect her for the rest of her career. The need to constantly manage this contradiction contributed to the isolation and difficulties of her later years.

Morrison became her third husband, but the marriage appears to have been primarily a business arrangement rather than a romantic relationship. He managed her career and helped her navigate the entertainment industry’s business complexities, but there’s little evidence of emotional intimacy between them. The marriage provided mutual benefits – professional management for her, social respectability for both – without requiring genuine romantic commitment.

International Recognition and Influence

In 1957, Tharpe was booked for a month-long tour of the United Kingdom by British trombonist Chris Barber. This tour introduced her music to European audiences who embraced her innovations with enthusiasm that often exceeded American appreciation. British musicians were particularly impressed by her guitar techniques and began incorporating her approaches into their own music.

The European tour demonstrated that Tharpe’s musical innovations had universal appeal that transcended cultural boundaries. British blues and rock musicians were developing their own interpretations of American music, and Tharpe’s work provided crucial influences that shaped the British Invasion of the 1960s. Musicians like Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and Keith Richards have acknowledged her impact on their musical development.

In April and May 1964, Tharpe returned to Europe as part of the Blues and Gospel Caravan, alongside Muddy Waters, Otis Spann, and other legendary American musicians. A concert recorded by Granada Television at a disused railway station in Manchester has become legendary among British musicians and critics. The performance has been compared to the Sex Pistols’ 1976 show at Manchester’s Lesser Free Trade Hall in terms of its influence on subsequent musical development.

The Manchester performance captured Tharpe at her artistic peak, demonstrating the guitar techniques and stage presence that had influenced American rock and roll. The unusual venue – a railroad station with the band performing on one platform while the audience sat on the opposite platform – created an intimate atmosphere that allowed viewers to appreciate the subtleties of her musical approach.

The influence of this performance on British musicians was immediate and lasting. Many guitarists who attended the show or saw the television broadcast incorporated Tharpe’s techniques into their own playing. The rhythmic approaches, chord voicings, and overall attitude she demonstrated became foundational elements of British rock music during its formative period.

But the European tours also highlighted the irony of Tharpe’s career trajectory. While American audiences were beginning to take her for granted or dismiss her as outdated, European musicians and critics recognized her as a foundational figure whose innovations had created the musical vocabulary that younger performers were using. This international recognition provided validation during a period when her domestic career was declining.

Health Struggles and Final Years

In 1970, Tharpe suffered a stroke that severely curtailed her performances and marked the beginning of her final decline. The stroke was followed by complications from diabetes that ultimately required the amputation of one of her legs. These health problems ended her touring career and left her largely dependent on others for basic care.

The health struggles of her final years were particularly tragic because they came just as music historians and critics were beginning to recognize her foundational contributions to rock and roll. The late 1960s had seen renewed interest in the roots of rock music, and Tharpe’s early recordings were being rediscovered by younger audiences who understood their historical significance.

But the medical expenses associated with her care consumed what savings she had accumulated during her career. Like many performers of her generation, she had limited financial planning and few resources to fall back on when she could no longer work. The music industry’s historical exploitation of black performers meant that even successful artists often faced poverty in their later years.

The isolation of her final years was deepened by the deaths of family members and longtime friends who had provided emotional support throughout her career. Katie Bell, her mother and earliest musical partner, had died earlier. Marie Knight had moved on to other relationships and career priorities. The network of relationships that had sustained her during her most productive years had largely disappeared.

On October 9, 1973, the eve of a scheduled recording session, Tharpe died in Philadelphia as a result of another stroke. She was 58 years old and planning a comeback that would never materialize. Her death received little attention from mainstream media, reflecting the general lack of recognition for her contributions that had characterized much of her later career.

She was buried at Northwood Cemetery in Philadelphia in a grave that remained unmarked for decades. This final indignity symbolized the broader erasure of her legacy from music history. While the performers she had influenced were being celebrated as innovators and pioneers, the woman who had created many of their signature techniques was forgotten.

The Systematic Erasure of Her Legacy

The decades following Tharpe’s death saw a systematic process of historical revision that minimized her contributions while amplifying those of white male performers who had borrowed her innovations. Rock and roll histories focused on figures like Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, and Little Richard while treating Tharpe as a footnote or ignoring her entirely.

This erasure wasn’t accidental. It reflected the music industry’s preference for narratives that positioned white male performers as creative innovators rather than acknowledging that many rock music fundamentals had been developed by black women working in gospel contexts. The commercial success of rock music created incentives to downplay its gospel and female origins.

Academic music histories also contributed to the erasure by focusing on formal musical analysis rather than cultural context. Scholarly approaches that emphasized technical innovation over social impact made it easier to ignore Tharpe’s contributions because her work crossed genre boundaries in ways that complicated traditional analytical frameworks.

The rise of rock criticism as a literary form during the 1960s and 1970s was dominated by white male writers who had limited understanding of gospel music and black cultural contexts. These critics developed canonical narratives about rock history that reflected their own cultural perspectives rather than accurate historical analysis. Their influence on subsequent scholarship and popular understanding was profound and lasting.

But the erasure also reflected broader patterns of how women’s contributions to technological and cultural innovation get minimized. Tharpe’s guitar innovations were as significant as those of any male performer, but because she was a woman working in a male-dominated field, her techniques were often attributed to men who had learned them from her recordings.

The intersection of racial and gender discrimination created particular challenges for preserving Tharpe’s legacy. As a black woman, she faced double marginalization that made it easier for later historians to ignore her contributions. The combination of racism and sexism in the music industry meant that her achievements received less documentation and promotion than those of white male performers.

Recognition and Resurrection

The resurrection of Tharpe’s reputation began in the 1990s as music historians and critics started examining rock history with more sophisticated analytical tools. Scholars like Gayle Wald began researching her life and career, uncovering evidence of her innovations and influence that had been overlooked or suppressed by earlier histories.

In 1998, the United States Postal Service issued a 32-cent commemorative stamp honoring Tharpe, providing official recognition of her historical significance. In 2007, she was inducted posthumously into the Blues Hall of Fame. In 2008, a concert was held to raise funds for a marker for her grave, and January 11 was declared Sister Rosetta Tharpe Day in Pennsylvania.

The most significant recognition came in 2018 when she was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as an Early Influence. This acknowledgment by the institution that had previously ignored her contributions represented a fundamental shift in how rock history was being understood and narrated.

Contemporary musicians have also played crucial roles in resurrecting her reputation. Artists like Johnny Cash, Aretha Franklin, and countless others have acknowledged her influence on their work. Guitar magazines and websites have featured analyses of her techniques that demonstrate their continuing relevance to contemporary musicians.

In 2023, Rolling Stone magazine named Tharpe the 6th greatest guitarist of all time, finally providing the recognition that her innovations deserved. This ranking placed her ahead of many male guitarists who had been influenced by her work but had received greater historical recognition.

The announcement in 2025 that Lizzo would portray Tharpe in an upcoming biopic represents another step in the process of restoring her proper place in music history. The involvement of a contemporary black female performer in telling her story ensures that her legacy will reach new audiences who can appreciate both her musical innovations and her significance as a pioneering female artist.

The Technology She Mastered

Tharpe’s mastery of electric guitar technology was revolutionary in ways that extended far beyond music. She was experimenting with electronic amplification and sound manipulation at a time when most people had never heard an electric guitar. Her innovations with distortion, sustain, and volume helped establish the sonic vocabulary that defines modern popular music.

Her technical expertise challenged assumptions about women’s relationships with technology that persist today. She understood electronics, acoustics, and signal processing in ways that enabled her to achieve specific artistic goals. This technical knowledge was combined with musical intuition that allowed her to use technology for expressive rather than merely functional purposes.

The guitar techniques she developed became standard elements of rock music that are still being used by contemporary performers. Her rhythmic approaches, melodic concepts, and harmonic innovations provided foundations that subsequent musicians built upon. The fact that many guitarists learned these techniques without knowing their origins speaks to how thoroughly her innovations became integrated into musical practice.

But her technological innovations also had broader cultural significance. By demonstrating that women could master complex technology and use it for creative purposes, she challenged gender stereotypes that limited women’s participation in technical fields. Her example showed that technological expertise and artistic creativity were compatible and mutually reinforcing.

The Revolution She Created

Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s legacy extends far beyond music into fundamental questions about who gets remembered and why. Her story demonstrates how cultural narratives get constructed, how they exclude certain voices and experiences, and how they can be challenged and revised through careful scholarship and persistent advocacy.

The gradual recognition of her contributions represents a broader shift in how we understand cultural history. Instead of accepting stories that center white male experiences while marginalizing others, historians and critics are developing more inclusive approaches that acknowledge the diversity of voices that have shaped our culture.

Her influence on subsequent generations of musicians is undeniable and documented. But her broader impact on cultural attitudes about gender, race, and artistic authenticity may be even more significant. She proved that women could be powerful, that black artists could innovate, and that spiritual music could transform secular culture.

The fact that rock and roll was invented by a black woman rather than the white men who typically receive credit changes how we understand the genre’s cultural significance. It reveals rock music as emerging from black spiritual traditions rather than white folk cultures. It positions women as technological innovators rather than passive consumers of male creativity.

Today, as women and marginalized communities continue fighting for recognition and respect in the music industry and beyond, Tharpe’s story provides both inspiration and strategic insights. She showed how individual talent and determination can create cultural change even in the face of systematic discrimination. But she also demonstrated the importance of documentation, promotion, and institutional recognition in preserving legacies for future generations.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe didn’t just influence rock and roll – she created it. Understanding her story accurately requires acknowledging that one of America’s most significant cultural innovations emerged from the hands and voice of a queer black woman who refused to be limited by other people’s expectations. Her legacy reminds us that revolutionary change often comes from unexpected sources and that the future belongs to those brave enough to plug in and turn up the volume.