Contents

ToggleIt’s 1919, and every winter morning across America starts the same way. Someone has to wake up before dawn, trudge down to a freezing basement, shovel coal into a furnace, and wait for warmth to slowly, unevenly creep through the house.

The person doing this backbreaking work was usually a woman, adding yet another exhausting task to her already endless list of household duties. Meanwhile, in Morristown, New Jersey, a Black woman named Alice Parker sat at her kitchen table, sketching out detailed engineering diagrams that would revolutionize how humanity heats its homes. Her invention would eventually free millions from the tyranny of coal shoveling and wood chopping, yet her name would disappear from history for nearly a century.

Alice Parker wasn’t supposed to be an inventor. Born in 1895, she entered a world that told Black women they had exactly two career options: domestic service or teaching in segregated schools. The fact that she would go on to patent a revolutionary heating system that forms the basis of modern central heating makes her story all the more extraordinary. What’s even more remarkable is that she did this without formal engineering training, without access to professional networks, and without any of the resources that her white male counterparts took for granted.

Growing Up Against the Odds

Alice H. Parker was born in Morristown, New Jersey, in 1895, right in the heart of the Jim Crow era. This wasn’t the Deep South with its explicit segregation laws, but Northern racism operated through different mechanisms—redlining, employment discrimination, and educational barriers that were just as effective at keeping Black Americans from opportunity. For a Black girl growing up in this environment, the path forward was supposed to be predetermined: limited education, marriage, and a lifetime of domestic work.

But Alice’s family had different ideas. Her parents, whose names have been lost to history thanks to the systematic erasure of Black family records, recognized their daughter’s exceptional intelligence. They scraped together enough money to send her to Howard University Academy, the prestigious high school affiliated with Howard University in Washington, D.C. This was no small feat—sending a Black daughter away for education required tremendous financial sacrifice and went against every societal expectation of the time.

At Howard Academy, Alice thrived. She graduated with honors in 1910, demonstrating particular aptitude in mathematics and science. This achievement alone was extraordinary—less than 1% of American women of any race earned high school diplomas at this time, and the percentage for Black women was virtually negligible. The fact that she graduated with honors from one of the most academically rigorous institutions available to Black students marked her as more than exceptional.

After graduation, census records show Alice working as a cook in Morristown, living with her husband who worked as a butler. This might seem like a step backward after her prestigious education, but it reflects the brutal reality of employment discrimination. No matter how educated or brilliant a Black woman was in 1910s America, white employers wouldn’t hire her for anything beyond domestic service. Alice Parker had the mind of an engineer trapped in the body of someone society insisted could only cook and clean for white families.

The Problem That Sparked Genius

Working as a cook gave Alice intimate knowledge of exactly how miserable home heating was in early 20th century America. Every morning before she could even begin cooking, she had to deal with the heating system. This meant hauling coal from the basement, shoveling it into the furnace, managing the fire throughout the day, cleaning out ashes, and repeating this exhausting cycle endlessly through the winter months.

New Jersey winters are brutal. Temperatures regularly drop below freezing, and the wind chill can make it feel even colder. In Alice’s era, keeping a house warm meant someone—usually the woman of the house or a domestic worker like Alice—had to wake up hours before everyone else to start the furnace. The heat distribution was terrible; rooms near the furnace would be stifling while distant rooms remained frigid. At night, families faced an impossible choice: let the fire die and wake up to a freezing house, or keep it burning and risk a catastrophic fire.

Alice experienced these problems not as abstract inconveniences but as daily physical ordeals that dominated her winter life. The coal dust that covered everything, turning white linens gray and coating dishes with grime. The constant interruptions to her cooking duties to check and feed the furnace. The impossibility of keeping an even temperature throughout the house, leading to endless complaints from the family she served. The very real danger of carbon monoxide poisoning from improper ventilation, which killed dozens of people every winter.

But while others accepted these hardships as inevitable facts of life, Alice Parker saw them as engineering problems with engineering solutions. She began to envision a different way—a heating system that would run on cleaner-burning natural gas instead of coal, that would distribute heat evenly throughout a building, and most importantly, that would operate automatically without constant human intervention.

The Revolutionary Design

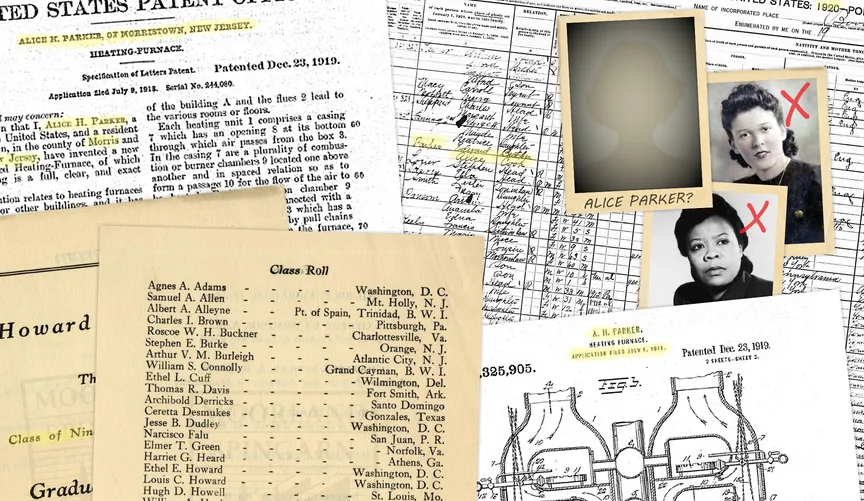

In 1919, Alice Parker did something that should have been impossible for someone of her background: she filed a patent application with the United States Patent Office. Patent applications required detailed technical drawings, precise specifications, and formal engineering language. They cost money to file and typically required the assistance of patent attorneys. For a Black woman working as a domestic servant to navigate this process successfully speaks to both her determination and her technical brilliance.

On December 23, 1919, the Patent Office granted Alice H. Parker patent number 1,325,905 for her “Heating Furnace.” The patent drawings she submitted weren’t rough sketches but detailed engineering diagrams showing every component of her revolutionary system. Her design included multiple heating units powered by natural gas, each controlled independently. Cold air would be drawn into the system, heated by gas combustion, and then distributed through ducts to different rooms. Most remarkably, her system included what she called “regulating means”—essentially primitive thermostats that could control the temperature in each zone of the house.

Think about how radical this was. Alice Parker essentially invented the concept of central heating as we know it today. Before her patent, heating systems were essentially glorified fireplaces or coal furnaces that heated a single point and relied on natural air circulation to spread warmth. Parker’s design introduced forced air circulation, zone heating, and automatic temperature regulation—all the fundamental principles of modern HVAC systems.

Her use of natural gas was particularly visionary. In 1919, natural gas infrastructure was still developing in most American cities. Coal was king, despite its obvious drawbacks. But Alice recognized that natural gas burned cleaner, required no storage space, needed no manual feeding, and could be controlled with simple valves. She was designing for a future that hadn’t arrived yet, anticipating the shift to natural gas that would transform American homes in the coming decades.

The Theft of Recognition

Here’s where Alice Parker’s story takes a familiar but infuriating turn. Her patent was granted, her design was brilliant, but she never manufactured her furnace. She couldn’t. No bank would loan money to a Black woman. No manufacturer would partner with her. No investors would take her seriously. The same systemic racism that had forced this brilliant inventor to work as a cook now prevented her from bringing her invention to market.

But the principles Alice Parker patented didn’t disappear. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, heating companies began developing furnaces that bore striking resemblances to Parker’s design. Natural gas furnaces with forced air circulation started appearing in American homes. Zone heating became a selling point for new housing developments. Automatic temperature controls evolved from luxury features to standard equipment. Every single element that Alice Parker had integrated into her 1919 patent became reality—just not with her name attached.

The companies that commercialized these innovations were run by white men who had access to capital, manufacturing facilities, and distribution networks. Some may have independently developed similar ideas, but the timing is suspicious. Parker’s patent was public record; anyone could have studied her designs and “improved” upon them just enough to avoid patent infringement. This was a common practice used to steal innovations from women and people of color who lacked the resources to defend their intellectual property.

By the 1950s, gas-fired central heating systems virtually identical in principle to Parker’s design had become standard in new American homes. The heating industry had become a multi-billion dollar sector of the economy. Fortunes were made by companies implementing Parker’s vision. Yet Alice Parker’s name appears in none of the industry histories, none of the corporate chronicles, none of the standard narratives about how central heating transformed American domestic life.

Parker’s Impact on Women’s Lives

To understand the true significance of Alice Parker’s invention, you have to understand what domestic life was like for women before central heating. Home heating wasn’t just about comfort—it was about survival, and the burden of maintaining that survival fell overwhelmingly on women.

In the coal and wood era, heating a home added hours of hard physical labor to women’s daily routines. They had to carry fuel, tend fires, clean ashes, scrub soot from walls and furniture, wash coal dust from linens, and somehow accomplish all their other household duties around these heating-related tasks. Women with young children faced the additional terror of keeping curious toddlers away from hot stoves and open flames. Every winter brought stories of children burned or houses destroyed because a mother’s attention lapsed for just a moment while managing both children and heating.

Alice Parker’s vision of automated, clean-burning heat would eventually liberate millions of women from this drudgery. Central heating meant women could focus on other aspects of household management—or increasingly, pursue opportunities outside the home. It’s no coincidence that women’s participation in the workforce increased dramatically in the decades after central heating became standard. When you don’t have to spend three hours a day managing coal furnaces, you have time for other pursuits.

Parker understood this because she lived it. As a domestic worker, she knew exactly how much of women’s labor went into heating homes. Her invention wasn’t just about engineering efficiency; it was about freeing women from backbreaking work that society had naturalized as “women’s work.” In this way, her heating system was a feminist innovation, even if she never described it in those terms.

The Safety Revolution Nobody Talks About

Before Alice Parker’s innovations, home heating was deadly. Coal furnaces killed families through carbon monoxide poisoning with frightening regularity. Wood stoves started fires that destroyed entire neighborhoods. Children suffered horrible burns from touching hot surfaces or falling against stoves. Every winter brought newspaper stories of families found dead in their beds, overcome by toxic fumes from malfunctioning heating systems.

Parker’s design addressed these dangers systematically. Natural gas, while not without risks, produces far less carbon monoxide than coal when properly burned. Her system of enclosed combustion chambers and dedicated ventilation ducts reduced the risk of toxic fumes entering living spaces. The automatic controls she envisioned would prevent the dangerous overheating that caused many fires. The ductwork that carried heated air eliminated the need for exposed hot surfaces that burned children.

When central heating systems based on Parker’s principles became widespread, deaths from heating-related causes plummeted. Thousands of lives were saved, hundreds of thousands of injuries prevented. Insurance companies saw claims from heating-related fires drop dramatically. Public health officials noted improvements in respiratory health as coal dust disappeared from homes. These massive improvements in public safety can be traced directly back to the innovations in Alice Parker’s 1919 patent, yet she receives no credit in public health histories.

The Environmental Pioneer

Alice Parker probably wasn’t thinking about climate change when she designed her gas furnace—the greenhouse effect wouldn’t become widely understood for decades. But her shift from coal to natural gas represented one of the first major steps toward cleaner residential energy use. Coal heating didn’t just warm homes; it poisoned entire cities. The “London fog” that features in so many Victorian novels wasn’t fog at all—it was toxic smog from millions of coal fires.

Natural gas burns far cleaner than coal, producing less particulate pollution, less sulfur dioxide, and less ash. Cities that transitioned from coal to gas heating saw immediate improvements in air quality. Rates of respiratory disease dropped. Buildings stopped turning black from soot. The urban environment became measurably healthier.

Parker’s innovation came at a crucial moment in American urban development. Cities were growing rapidly, and if coal had remained the primary heating fuel, the health consequences would have been catastrophic. Her gas heating system provided a cleaner alternative just as American cities needed it most. While natural gas is still a fossil fuel with its own environmental impacts, the shift from coal to gas that Parker pioneered bought crucial time and saved countless lives from air pollution.

The Pattern of Erasure

Alice Parker’s disappearance from the historical record follows a depressingly familiar pattern for women inventors, particularly women of color. First, their innovations are dismissed as too simple or impractical. Then, when men implement similar ideas, those men are credited as the true inventors while the women are forgotten. Finally, historians looking back assume that since women “didn’t invent anything significant,” they must not have been capable of innovation.

HerWiki is built and maintained by the support of amazing readers like you. If this story inspired you, join the cause and help us make HerWiki bigger and better.

This erasure was systematic and deliberate. Patent records from Parker’s era show hundreds of patents granted to women, yet virtually none of these women appear in standard histories of American innovation. When the Smithsonian created its first exhibits on American inventors, not a single woman was included. Engineering schools teaching the history of HVAC systems never mentioned Alice Parker, even though her patent preceded most of the “founding fathers” of the industry.

The erasure extends beyond just forgetting names. Parker’s approach to engineering—solving problems through lived experience rather than formal training—has been devalued as “not real engineering.” Her focus on domestic comfort and safety was dismissed as “women’s concerns” rather than recognized as fundamental to human wellbeing. Her identity as a Black woman led historians to assume she couldn’t possibly have made significant technical contributions.

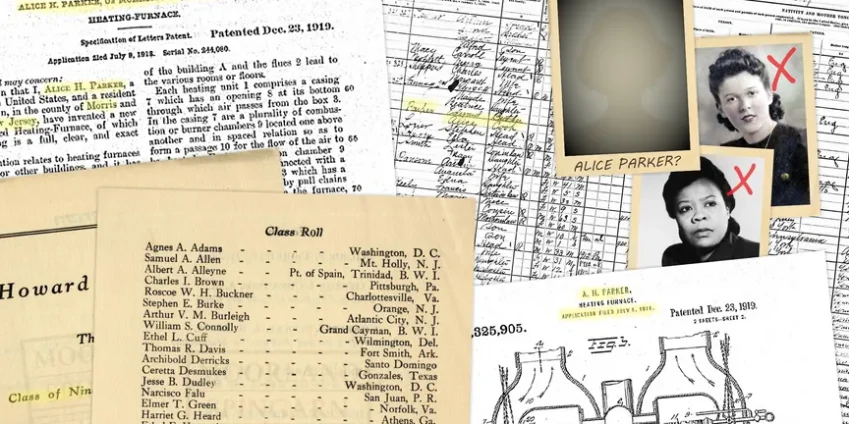

Recent efforts to recover Parker’s story have faced additional challenges. Many records simply don’t exist—destroyed by time, neglect, or deliberate disposal. Photos commonly attributed to Parker online have been revealed to be of other people entirely. Even her death date remains uncertain, with some sources suggesting 1920 though this seems improbably soon after her patent. The very incompleteness of her biographical record testifies to how thoroughly she was erased.

The Modern Legacy

Today, every forced-air heating system in America operates on principles Alice Parker established in 1919. When you adjust your thermostat to different temperatures in different rooms, you’re using zone heating—Parker’s innovation. When your furnace automatically cycles on and off to maintain comfortable temperatures, it’s following the control principles she patented. When natural gas flows through pipes to heat your home cleanly and efficiently, you’re benefiting from Parker’s vision.

The modern HVAC industry generates over $100 billion annually in the United States alone. Smart thermostats like Nest and Ecobee are essentially highly sophisticated versions of the temperature controls Parker first imagined. Energy-efficient heating systems that reduce carbon emissions build on the foundation of gas heating she pioneered. Every improvement in home heating technology over the last century has been, in some sense, a refinement of Alice Parker’s original breakthrough.

Yet until very recently, Parker received no recognition for any of this. No heating company bears her name. No engineering school has a Parker Building. No industry association gives out an Alice Parker Award. The fortune and fame that should have been hers went instead to the men who commercialized her ideas without attribution.

The Recovery of a Revolutionary

In recent years, historians and activists have begun recovering Alice Parker’s story from obscurity. The National Society of Black Physicists has honored her as a pioneering inventor. The New Jersey Chamber of Commerce established the Alice H. Parker Women Leaders in Innovation Awards. Social media campaigns during Black History Month have introduced her story to new generations.

But this recognition, welcome as it is, cannot undo the injustice of her erasure. Parker never received royalties from the billions of dollars generated by her innovations. She never saw her name on the heating systems that warmed millions of homes. She never experienced the satisfaction of being acknowledged as the visionary engineer she was.

What makes Parker’s story particularly poignant is knowing how many other Alice Parkers there must have been—brilliant women whose innovations were stolen, whose contributions were erased, whose names we’ll never know. Parker was lucky enough to have her patent survive, giving us at least a glimpse of her genius. How many others filed no patents, left no records, disappeared completely from history?

A Revolution from the Kitchen Table

Alice Parker’s story forces us to reconsider what we think we know about innovation and who we recognize as inventors. She had no engineering degree, no laboratory, no team of assistants. She had a kitchen table, a keen understanding of thermodynamics gained from lived experience, and the audacity to believe she could solve a problem that affected millions.

Her approach to innovation—starting from personal experience of a problem and working toward systematic solutions—challenges the myth that important inventions only come from university laboratories or corporate R&D departments. Parker proved that revolutionary innovations could come from anyone, anywhere, if they had the insight to recognize a problem and the persistence to develop a solution.

The heating system she envisioned transformed not just how we warm our homes but how we live our lives. It freed women from hours of daily drudgery. It saved thousands of lives from fires and poisoning. It cleaned the air in our cities. It established principles that still guide engineering design today. All of this from a Black woman working as a cook in New Jersey, sketching her revolutionary ideas at a kitchen table.

The Unfinished Revolution

Alice Parker’s true revolution isn’t just in the heating systems that warm our homes—it’s in the questions her story raises about innovation, recognition, and justice. How many world-changing inventions have we lost because their creators lacked access to capital? How many brilliant minds have been wasted in menial labor because of discrimination? How much further advanced would our technology be if we hadn’t systematically excluded most of humanity from the innovation process?

Parker’s patent proves that genius doesn’t respect the boundaries society tries to impose. She was Black in a racist society, female in a sexist world, working-class in a system that respected only wealth, yet she designed a system so advanced that it took decades for manufacturing to catch up to her vision. Her story demolishes every assumption about who can be an inventor, what counts as engineering, and where innovation comes from.

Today, as we grapple with climate change and energy efficiency, Parker’s century-old insights remain relevant. Her vision of clean-burning, efficiently distributed, automatically controlled heating points toward the kind of sustainable systems we need for the future. Modern innovations like geothermal heating and heat pumps build on the foundation she established. In a very real sense, we’re still catching up to Alice Parker’s vision.

The recovery of Parker’s story isn’t just about correcting the historical record—though that’s important. It’s about recognizing that innovation has always been more diverse than our histories acknowledge. It’s about understanding that solving humanity’s greatest challenges requires input from all of humanity, not just the privileged few. It’s about ensuring that the Alice Parkers of today receive the recognition, resources, and rewards their innovations deserve.

Alice H. Parker died sometime in the early 1920s, her exact date of death lost to the same historical neglect that erased her contributions. She never saw her heating system transform American homes. She never knew that her principles would one day warm hundreds of millions of people worldwide. She never received a penny from the massive industry built on her innovation.

But her patent survives, a testament to her genius and a rebuke to everyone who said Black women couldn’t be inventors. Every time we adjust our thermostats, we’re using Alice Parker’s technology. Every comfortable winter night in a warm home is a monument to her vision. Every child who grows up without the burden of tending coal furnaces benefits from her brilliance.

Alice Parker revolutionized how humanity heats its homes. She deserves to be remembered not as a footnote in African American history or a curiosity in women’s history, but as one of the most important inventors of the 20th century. Her story reminds us that innovation can come from anywhere, that genius doesn’t respect society’s boundaries, and that the comfortable world we inhabit was built by people whose names we’ve been taught to forget.

The next time your furnace kicks on automatically, warming your home with clean-burning gas distributed evenly through hidden ducts, remember Alice H. Parker. Remember the woman who looked at the backbreaking labor of home heating and said: there has to be a better way. Remember the cook who thought like an engineer, the Black woman who refused to accept limits, the inventor whose vision transformed the world even as the world forgot her name.

Alice Parker didn’t just invent central heating. She proved that the future has always belonged to those brave enough to imagine it differently, regardless of what society tells them they’re allowed to dream.