Contents

ToggleMost people think the founding fathers created American democracy. They wrote the Constitution, fought the Revolutionary War, and built the government. But here’s what they don’t tell you in history class: American politics was actually broken and violent until one woman figured out how to fix it.

Before Dolley Madison came along, political opponents would literally shoot each other in duels. Members of different parties couldn’t even be in the same room without fighting. The entire democratic experiment was falling apart because men kept trying to kill each other over political disagreements.

Dolley Madison saw this chaos and did something nobody had tried before. She brought enemies together at dinner parties. She made them talk instead of fight. She created the entire system of political networking that makes democracy actually work. Without her, American politics would have destroyed itself before the country even got started.

Growing Up Under Strict Control

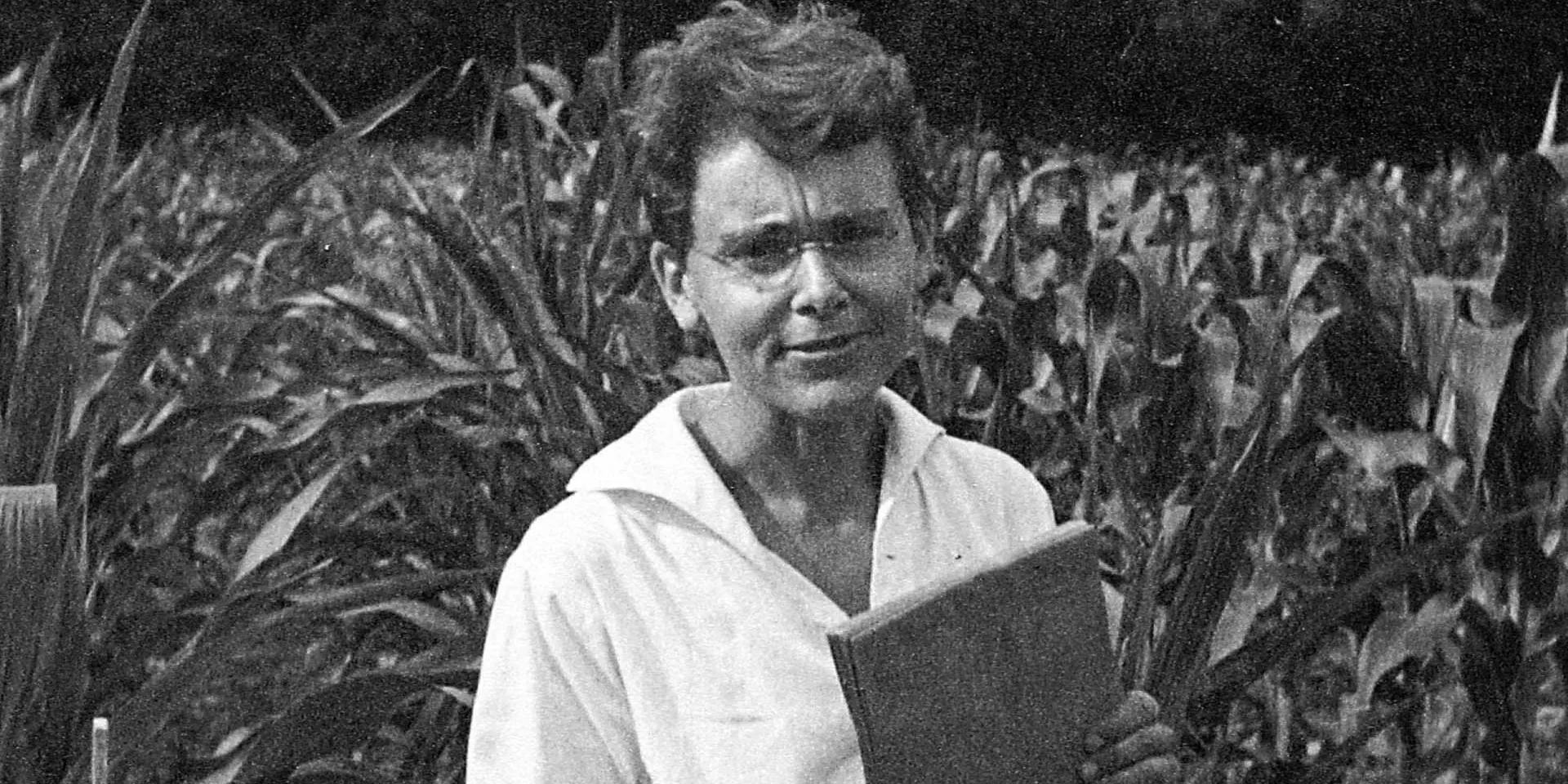

Dolley Payne was born on May 20, 1768, in North Carolina to John and Mary Payne. Her father was a devout Quaker who controlled every aspect of his family’s life through religious rules. The Quaker faith dictated what she could wear, who she could talk to, what she could read, and how she had to behave every minute of every day. Girls especially faced severe restrictions. They couldn’t express opinions, show their personalities, or make their own choices about anything.

When Dolley was just a baby, her family moved back to Virginia, where they owned a 176-acre farm. She spent her childhood doing hard physical labor on the farm alongside her seven siblings. Her father didn’t believe girls needed real education, so while boys in wealthy families got tutors and went to academies, Dolley received only basic instruction in reading and household management. The Quaker meetings she attended every week reinforced the message that women existed only to serve men and God, in that order.

The family’s life revolved entirely around her father’s decisions and moods. When John Payne decided to free the family’s enslaved workers in 1783, it was presented as his moral awakening, though it only became legal in Virginia in 1782. When he decided to move the entire family to Philadelphia that same year, nobody asked the women what they wanted. Dolley was fifteen years old and had never been allowed to make a single decision about her own life.

Forced Into Marriage

Philadelphia should have meant more freedom for a teenage girl, but Dolley’s father maintained absolute control. The family lived at 57 North Third Street, where John Payne tried to start a starch manufacturing business. He failed completely. The Quaker community saw his business failure as moral weakness and expelled him from their meetings. This humiliation destroyed him, and he died on October 24, 1792.

But before dying, John Payne made one last decision to control his daughter’s life. He arranged her marriage to John Todd, a Philadelphia lawyer, without asking Dolley what she wanted. Historical records show she had actually rejected Todd’s proposals before, but her dying father’s arrangement left her no choice. Quaker daughters who refused their father’s chosen husbands faced complete exile from their families and communities. On January 7, 1790, at age 21, Dolley married a man she didn’t choose because the patriarchal system gave her no other option.

The marriage at least provided some happiness. Todd genuinely cared for Dolley, and she grew to love him. They had two sons: John Payne (called Payne) born February 29, 1792, and William Temple born July 4, 1793. For a brief moment, Dolley had the family life she wanted, even if she hadn’t chosen how it started.

Then yellow fever struck Philadelphia in August 1793. The epidemic killed 5,019 people in four months. Dolley lost her husband, baby William, her mother-in-law, and father-in-law. In a matter of weeks, the 25-year-old widow was left alone with a toddler and no money. Her husband had left her funds in his will, but his brother, the executor, refused to give them to her. She had to sue her own brother-in-law just to get the money her dead husband wanted her to have. Even in death, men controlled women’s survival.

Breaking Religious Law for Love

Aaron Burr helped Dolley with her lawsuit and then introduced her to his friend James Madison in May 1794. Madison was 43, a lifelong bachelor, and definitely not a Quaker. By August, he had proposed marriage. Dolley faced an impossible choice: marry outside her faith and be expelled from the only community she’d ever known, or remain a struggling widow forever.

She chose love and independence over religious control. On September 15, 1794, she married James Madison. The Quakers immediately expelled her for marrying outside the faith, cutting her off from her entire social network and spiritual community. They considered her damned and corrupted. But this expulsion actually freed her from the strict rules that had controlled her entire life. She started attending Episcopal services, wore colorful clothes, and spoke her mind at social gatherings.

The couple lived in Philadelphia for three years while James served in Congress. In 1797, he retired from politics and they moved to Montpelier, his family’s plantation in Virginia. For three years, Dolley finally had peace and stability. She expanded the house, created beautiful gardens, and built the social skills that would later transform American politics.

Revolutionizing Political Culture

When Thomas Jefferson became president in 1800, he asked James Madison to serve as Secretary of State. The Madisons moved to Washington, taking a large house on F Street. Dolley immediately recognized something other political wives hadn’t: the new capital city needed a social structure to make government actually function. Politicians from different parties literally refused to speak to each other. They challenged each other to duels over minor disagreements. Democracy was failing because men were too proud and angry to compromise.

Jefferson was a widower who hated social events. He would only meet with members of one political party at a time, keeping them strictly separated. This made negotiation and compromise impossible. Dolley Madison saw the problem and created the solution. She started hosting elaborate dinner parties where she invited members of both political parties. She arranged the seating to force political opponents to sit near each other. She directed conversations toward common ground instead of differences.

At first, the men resisted. They complained about having to socialize with their enemies. But Dolley’s charm was strategic and irresistible. She remembered every person’s name, their children’s names, their interests and concerns. She made each guest feel like the most important person in the room. Slowly, the men started talking to each other at her parties. They discovered they could disagree about politics without hating each other personally. They began making deals and compromises over dinner instead of threatening violence.

Dolley became so essential to Washington’s functioning that she created an international incident just by walking into a room. In 1803, Jefferson escorted her to dinner before the wife of Anthony Merry, the English ambassador. This breach of protocol caused such outrage it became known as the Merry Affair and damaged American-British relations for years. The fact that Dolley’s social position could cause international crises proved how powerful she had become in the political system.

Creating the Role of First Lady

When James Madison became president in 1809, Dolley finally had an official position as White House hostess. The term “First Lady” didn’t exist yet because nobody had imagined a president’s wife could have real political influence. Previous presidents’ wives had stayed in the background, hosting small tea parties and avoiding political discussions. Dolley transformed the role into something powerful and essential.

She redecorated the White House to make it a symbol of American democracy rather than a cold government building. She chose every piece of furniture, every painting, every curtain to send a message about American values and power. She created elaborate social events that brought together politicians, diplomats, artists, and thinkers. Her weekly receptions became the place where real political business happened.

Foreign diplomats realized that influencing Dolley meant influencing American policy. She befriended the wives of ambassadors from Spain, France, and other nations, creating informal diplomatic channels that prevented conflicts. She gathered intelligence from social conversations and passed it to her husband. She shaped public opinion by controlling who got invited to important events and who got excluded.

Congress recognized her unprecedented influence by granting her an honorary seat on the floor of Congress – the first and only First Lady to receive this honor. She was also the first American to respond to a telegraph message, showing her embrace of new technology and progress. Male politicians initially resented her power, but they couldn’t deny that government worked better with her involvement.

Saving America’s History

In 1812, America declared war on Britain. By 1814, British forces were marching toward Washington to burn the capital. On August 23, as the enemy approached and government officials fled in panic, Dolley Madison refused to leave the White House until she saved the portrait of George Washington painted by Gilbert Stuart.

Male officials told her she was wasting precious time on a painting. They ordered her to leave immediately. But Dolley understood something these men didn’t: symbols matter. That portrait represented American independence and democracy. Letting the British burn it would be surrendering America’s identity and history.

She ordered her enslaved servant Paul Jennings to help save the painting. When they couldn’t unscrew it from the wall fast enough, she commanded them to break the frame and cut out the canvas. She personally ensured the portrait reached safe hands before finally fleeing the city. She also saved critical government documents and other treasures that would have been lost forever.

For generations, historians tried to erase Dolley’s heroism from this story. They gave credit to male servants or claimed she only gave orders while men did the real work. But primary sources, including Jennings’ own memoir, confirm that saving these national treasures was Dolley’s decision and her accomplishment. Without her insistence on preserving America’s symbols and documents, the British would have destroyed irreplaceable pieces of American heritage.

When she returned to Washington after the British retreat, the White House was a charred ruin. She and James moved into the Octagon House and immediately began rebuilding both the building and the government’s morale. While men despaired over the destruction, Dolley organized social events to prove that American democracy couldn’t be destroyed by burning a few buildings.

Abandoned by the System She Helped Build

After James Madison’s presidency ended in 1817, the couple retired to Montpelier. James died on June 28, 1836, leaving Dolley to manage the plantation alone. This is when the patriarchal system she had spent her life navigating turned truly cruel. Her son Payne Todd, from her first marriage, was an alcoholic who had never held a job or taken any responsibility. But as a man, he had legal control over much of her property.

Payne’s alcoholism and gambling destroyed Dolley’s financial security. In 1830, he went to debtor’s prison in Philadelphia. Dolley had to sell land in Kentucky and mortgage half of Montpelier to pay his debts. But Payne learned nothing. He continued drinking, gambling, and destroying everything Dolley tried to save.

After James died, Dolley spent a year organizing and copying his papers, including his invaluable notes from the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Congress eventually paid her $55,000 for these documents, but it wasn’t enough to cover Payne’s continuing debts. She tried desperately to make the plantation profitable, but Payne’s incompetence and addiction made it impossible.

By 1837, Dolley had to return to Washington, leaving Payne in charge of Montpelier. This was like putting an arsonist in charge of a match factory. Within a few years, he had destroyed everything. Dolley was forced to sell Montpelier, including the enslaved people who worked there, just to avoid complete bankruptcy.

HerWiki is built and maintained by the support of amazing readers like you. If this story inspired you, join the cause and help us make HerWiki bigger and better.

Dying in Poverty After Saving the Nation

In Washington, Dolley lived in a house on Lafayette Square with her sister Anna. She tried to maintain her dignity while facing absolute poverty. The woman who had essentially created American political culture, who had saved priceless national treasures, who had made democracy functional, was now struggling to afford food.

She attempted to sell more of James Madison’s papers to Congress, but they delayed and negotiated while she suffered. Her enslaved servant Paul Jennings, whom she had brought from Montpelier, tried to buy his freedom. She had written a will in 1841 promising to free him after her death, but desperation forced her to sell him for $200 in 1846. Senator Daniel Webster later bought Jennings and freed him.

Jennings would later write in his memoir about Dolley’s final years: “In the last days of her life, before Congress purchased her husband’s papers, she was in a state of absolute poverty, and I think sometimes suffered for the necessaries of life.” This man whom she had enslaved was now giving her money from his own pocket to buy food. He regularly brought her baskets of provisions because the American government let its most important female founder starve.

Congress finally agreed in 1848 to buy the rest of Madison’s papers for $25,000, giving Dolley just enough to survive her final year. She had spent decades preserving these documents that were crucial to understanding America’s founding, and Congress made her beg for payment while she went hungry.

On February 28, 1844, while accompanying President John Tyler on the USS Princeton, Dolley survived an explosion that killed six people, including two cabinet secretaries. At 76 years old, she had outlived most of her generation and survived yet another brush with death. But she couldn’t survive the poverty and abandonment that American society inflicted on widowed women.

The Real Legacy Hidden by History

Dolley Madison died on July 12, 1849, at age 81 in her Washington home. She was initially buried in the Congressional Cemetery before being reinterred next to James at Montpelier. For decades after her death, historians minimized her accomplishments and credited men for her innovations. They called her parties “mere social events” instead of recognizing them as the foundation of American political culture.

But the truth is undeniable when you look at the evidence. Before Dolley Madison, American democracy was violent, dysfunctional, and on the verge of collapse. Politicians literally killed each other over disagreements. Different parties couldn’t occupy the same building without fighting. There was no mechanism for compromise or peaceful negotiation between opposing factions.

Dolley created the entire social infrastructure that makes democracy possible. She invented the concept of bipartisan cooperation. She established informal diplomatic channels that prevented wars. She saved irreplaceable national treasures from destruction. She defined the role of First Lady as a position of real political influence rather than decorative hosting.

Modern surveys of historians consistently rank her among the top six First Ladies in American history. In 1999, the U.S. Mint issued a silver dollar commemorating the 150th anniversary of her death. Virginia named State Route 123 the Dolley Madison Boulevard. These honors came centuries late for a woman who fundamentally shaped American democracy.

The most revealing part of Dolley’s story is how hard the patriarchal system worked to destroy her even after she had saved it. She was expelled from her religion for choosing her own husband. She was left in poverty by her alcoholic son who had legal control over her property. She had to sell human beings into slavery to avoid starvation because the government wouldn’t pay her for preserving crucial historical documents. She died having to accept charity from a man she had once enslaved because America abandoned the woman who had taught it how to function as a democracy.

Dolley Madison’s life proves that women have always been essential to American success, even when the system tried to erase their contributions. She took the violent, chaotic mess that men had made of early American politics and transformed it into a functional democracy through sheer force of intelligence and will. She created the social and political structures that still govern Washington today. Without her, American democracy would have destroyed itself before it ever truly began.

The men who wrote the Constitution gave America its laws. But Dolley Madison gave America its soul. She showed a young nation how to resolve conflicts without violence, how to build coalitions across party lines, and how to preserve its history for future generations. Every peaceful transfer of power, every bipartisan compromise, every political negotiation that happens in Washington today exists because one woman refused to accept that politics had to be violent and cruel.

That’s the real story of Dolley Madison: not just a First Lady who threw nice parties, but the woman who saved American democracy from the men who nearly destroyed it. She deserves to be remembered not as James Madison’s wife, but as the founder who created the political culture that made America possible.