Contents

ToggleIn 1546, a Flemish woman arrived at the English royal court carrying paintbrushes and a revolutionary approach to miniature painting. Levina Teerlinc would spend the next thirty years serving four English monarchs and earning more money than the famous Hans Holbein ever did. Yet for centuries after her death, her paintings were attributed to men, her contributions erased, and her name nearly forgotten. This is the story of the woman who painted queens and shaped how we see the Tudor dynasty today.

Early Life in Bruges

Born in Bruges sometime in the 1510s, Levina entered a world where art was a family business. Her father, Simon Bening, was one of the most celebrated manuscript illuminators of his time. Her mother, Catherine van der Goes, came from an artistic dynasty that included the renowned painter Hugo van der Goes. Levina was one of five daughters, and unlike most girls of her era, she didn’t learn needlework and household management as her primary education. Instead, she learned to grind pigments, prepare vellum, and wield brushes with microscopic precision.

The workshop of Simon Bening was essentially a medieval art factory. Wealthy patrons from across Europe commissioned illuminated manuscripts, and the Bening workshop produced some of the finest examples of the dying art form. As printing presses began replacing hand-copied books, the Benings adapted by focusing on luxury items for the ultra-wealthy. Young Levina learned not just technique but also the business of art: how to manage commissions, work with demanding clients, and maintain the highest standards of craftsmanship.

While her sisters helped with the less skilled aspects of manuscript production, Levina showed exceptional talent. Her father recognized this and trained her in the most difficult techniques of miniature painting. This wasn’t common. Most master artists jealously guarded their secrets, passing them only to sons or male apprentices. But Simon Bening saw something in his daughter that transcended the usual gender boundaries of the profession.

By her twenties, Levina had mastered the intricate art of painting on vellum. She could create portraits smaller than a playing card with details so fine they required a magnifying glass to fully appreciate. Her speciality became portrait miniatures, tiny paintings that captured not just physical likeness but personality and status. These weren’t mere decorations; they were diplomatic tools, love tokens, and symbols of power that could fit in the palm of your hand.

The Journey to England

In 1545, Levina married George Teerlinc, a man from Blankenberge whose family had connections to the English wool trade. This marriage wasn’t just a personal union; it was a strategic move that would change both their lives. Within a year of their wedding, the couple received a royal invitation: King Henry VIII wanted Levina to become his court painter.

The invitation itself was remarkable. Henry VIII, who had broken from the Catholic Church and declared himself head of the Church of England, was not known for his progressive views on women. He had famously executed two of his six wives and was in the process of establishing male primogeniture as the cornerstone of English succession law. He was one of the most cruel, inhumane, and misogynistic monarchs of the Tudor lineage. Yet here he was, offering a woman one of the most prestigious artistic positions in his kingdom.

Why Levina? The answer lies in the peculiar circumstances of Tudor England. Hans Holbein the Younger, Henry’s previous court painter, had died of plague in 1543. The king desperately needed someone who could create the intimate portrait miniatures that had become essential tools of Tudor diplomacy and courtship. These tiny paintings were sent to foreign courts during marriage negotiations, exchanged between nobles as signs of favor, and worn as jewelry to display loyalty. No English artist had Holbein’s skill, and hiring from Catholic countries like Spain or Italy was politically impossible.

Levina represented a perfect solution. Flanders, though Catholic, maintained strong trade ties with England. Her father’s reputation guaranteed her skill, and her gender, paradoxically, made her less threatening. A female artist couldn’t establish a competing workshop or train apprentices who might challenge English artists. She was simultaneously foreign enough to have the needed skills and powerless enough not to threaten the existing order.

The Court Artist

When Levina arrived at the English court in 1546, she entered a world of extraordinary complexity and danger. Henry VIII was in his final years, bloated and paranoid, surrounded by courtiers who could find themselves in the Tower of London with a single wrong word. Yet Levina navigated this treacherous environment with remarkable success. Her appointment came with an annual salary of forty pounds, a fortune for an artist and notably more than Holbein had ever received.

The higher salary wasn’t just recognition of her skill; it was practical necessity. As a woman, Levina couldn’t supplement her income the way male artists did. She couldn’t take private commissions without royal permission, couldn’t establish a public workshop, and couldn’t train paying apprentices. The crown had to pay her enough to maintain the lifestyle expected of a court artist, including fine clothes, quality materials, and a respectable household.

Levina’s first major challenge came with the death of Henry VIII in 1547. The nine-year-old Edward VI became king, and Levina had to prove her worth to an entirely new power structure. The boy king’s advisors, led by Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, were Protestant reformers who viewed art with suspicion. Religious paintings were being destroyed across England, and artists who had painted saints and Madonnas found themselves unemployed or worse.

But Levina had never painted religious scenes. Her specialty, portrait miniatures, aligned perfectly with Protestant values. These weren’t idolatrous images to be worshipped but documentary records of real people. She painted the young king multiple times, creating images that showed him as both a child and a divinely appointed ruler. Her miniatures became part of Edward VI’s propaganda campaign, tiny portraits that could be distributed to supporters and worn as badges of loyalty.

The Female Touch

What made Levina’s work distinctive wasn’t just her technical skill but her perspective as a woman in a male-dominated world. Her portraits, particularly of women, showed a psychological depth that male artists often missed. When she painted Lady Katherine Grey in the 1550s, she captured not just the young woman’s beauty but the intelligence and determination that would later lead Katherine to secretly marry against Queen Elizabeth’s wishes.

Male artists of the period typically painted women as either Madonna figures or temptresses, reducing complex individuals to simple archetypes. Levina painted women as people. Her portrait of Katherine Grey shows a young woman holding a small book, likely a prayer book, but her expression suggests someone thinking about more than just devotion. There’s a wariness in her eyes, a sense of someone who knows she’s being watched and judged.

This psychological insight extended to her male subjects as well. Her attributed portrait of the young Edward VI shows not a divine king but a sick child trying to look strong. The thin shoulders, the pale complexion, the eyes that seem too large for the face, all speak to the tuberculosis that would kill him at fifteen. Yet there’s dignity in the portrait too, a sense of a boy trying desperately to fulfill an impossible role.

Levina’s technique was also revolutionary. While Holbein had painted with precise, controlled strokes that created almost photographic realism, Levina used a looser, more impressionistic style. Her brushwork was criticized by some as “weak” or “thin,” but this was a deliberate choice. The softer style allowed her to capture fleeting expressions and emotional states that Holbein’s harder style couldn’t convey.

Surviving Mary I

When Edward VI died in 1553, England plunged into crisis. The attempt to place Lady Jane Grey on the throne failed, and Mary I, Henry VIII’s eldest daughter, became England’s first queen regnant. For many Protestant courtiers, this meant exile or execution. For Levina, it meant adaptation.

Mary I was Catholic, devoted to returning England to the Roman faith. She married Philip of Spain, reinstated the Latin Mass, and began burning Protestant heretics. Yet she kept Levina as her court painter. This might seem surprising, but it made perfect political sense. Levina was from Flanders, part of the Spanish Netherlands under Philip’s control. She was technically a Catholic, though there’s no evidence she was particularly devout. Most importantly, she was already there, already proven, and already painting.

Levina’s work during Mary’s reign shows remarkable political dexterity. She painted the queen in ways that emphasized her legitimacy rather than her religion. A remarkable miniature from this period shows Mary distributing Maundy money to the poor, fulfilling the traditional role of English monarchs. Another shows her touching for the “King’s Evil,” the belief that royal touch could cure scrofula. These weren’t Catholic practices but ancient English royal traditions that predated the Reformation.

In 1556, Levina presented Mary with a New Year’s gift: “a small picture of the Trinity.” This was potentially dangerous. Religious images were controversial, and choosing the wrong iconography could mark someone as either too Catholic or too Protestant. Levina chose the safest possible subject, the Trinity, which was accepted by both faiths. In return, Mary gave her a silver-gilt salt cellar, a valuable gift that showed royal favor.

The relationship between Levina and Mary reveals the complex reality of Tudor women’s lives. Both were professionals in male-dominated fields, both had to navigate constantly shifting political and religious landscapes, and both understood that survival required flexibility. Levina’s portraits of Mary show not the “Bloody Mary” of Protestant propaganda but a woman aged beyond her years by disappointment and illness, trying desperately to produce an heir and secure her legacy.

The Elizabethan Golden Age

When Elizabeth I ascended the throne in 1558, Levina faced her fourth monarch in twelve years. Elizabeth, unlike her siblings and father, would reign for forty-five years, and Levina would serve her for eighteen of them. This was Levina’s most productive period, though ironically, it’s also when her work becomes hardest to identify definitively.

Elizabeth understood the power of image like no monarch before her. She controlled her portraits obsessively, decreeing that only approved patterns could be used for her likeness. Unauthorized portraits were destroyed, and artists who depicted her unflatteringly faced punishment. Yet she trusted Levina, a woman who had served her father, her brother, and her sister, to capture her image.

Levina’s portraits of Elizabeth show the evolution of the queen from young woman to powerful monarch. An early miniature from around 1559 shows Elizabeth in her coronation robes, but the face is still soft, almost vulnerable. The eyes are watchful, the mouth slightly tense. This is a woman who knows she’s surrounded by threats, whose legitimacy is questioned, whose right to rule is constantly challenged.

Later portraits show a transformation. Elizabeth’s face becomes mask-like, idealized, ageless. Levina understood that she was no longer painting a person but creating an icon. The queen’s portraits became increasingly symbolic: the pelican jewel representing self-sacrifice, the phoenix representing renewal, the roses and lilies representing the union of York and Lancaster. These weren’t just portraits; they were political statements encoded in jewels and symbols.

What’s remarkable is that Levina managed to maintain her position despite being Catholic in Protestant England, Flemish in xenophobic England, and female in patriarchal England. She did this by making herself indispensable. She wasn’t just a painter; she was a keeper of royal image, a creator of propaganda, a magician who could capture power in pigment and gold.

The Business of Art

While serving as court painter, Levina also had to manage her household and family. She and George had one son, Marcus, who survived to adulthood. Managing a household in Tudor London required significant income, and Levina’s forty pounds annual salary, while generous, had to cover materials, assistants, and living expenses.

Portrait miniatures required expensive materials. The vellum had to be perfectly prepared, stretched on cards made from expensive pasteboard. The pigments included ultramarine from Afghanistan, vermillion from Spain, and gold leaf beaten so thin it could float on breath. Each portrait might take weeks to complete, with multiple sittings required for important subjects.

Levina also designed official documents and seals. The Great Seal of England, used to authenticate royal documents, bore designs attributed to her. These weren’t just artistic exercises but crucial instruments of state power. Every charter, every patent, every official decree bore impressions from seals she designed. Her artistic vision literally authorized the acts of monarchy.

HerWiki is built and maintained by the support of amazing readers like you. If this story inspired you, join the cause and help us make HerWiki bigger and better.

The workshop Levina maintained would have been unlike any other in London. While male artists’ workshops were essentially public spaces where clients could visit and apprentices learned their trade, Levina’s had to be private. As a respectable woman, she couldn’t have strange men traipsing through her workspace. Her assistants would have been family members or trusted servants, probably women who could help with the less skilled aspects of production.

This isolation had consequences. Male artists learned from each other, shared techniques, and competed for innovations. Levina worked in relative solitude, developing her own techniques without the constant feedback and rivalry that drove artistic development. This may explain why her style remained relatively consistent throughout her career while other artists’ work evolved dramatically.

Training the Next Generation

One of Levina’s most significant but uncredited contributions was likely training Nicholas Hilliard, who would become England’s most celebrated miniaturist. Hilliard started working as a goldsmith and somehow learned the techniques of portrait miniature painting. The timing and circumstances strongly suggest Levina was his teacher.

The evidence is circumstantial but compelling. Hilliard’s early work shows techniques specific to Levina’s style: the same loose brushwork, the same approach to modeling faces, the same way of applying gold leaf for jewelry and decoration. He began producing miniatures just as Levina’s production decreased, suggesting a transition of responsibilities.

But Levina couldn’t publicly claim Hilliard as her student. The goldsmith’s guild would never have accepted that one of their members learned from a woman. Hilliard himself never acknowledged her influence, instead claiming he learned from studying Holbein’s work. This erasure was typical. Male artists could build dynasties on their teaching, with students proudly claiming their master’s lineage. Female artists’ pedagogical contributions disappeared.

If Levina did train Hilliard, she gave England its national art form. Hilliard’s miniatures defined Elizabethan visual culture, and his students carried the tradition into the seventeenth century. The techniques Levina brought from Flanders, filtered through her unique perspective and passed to Hilliard, became quintessentially English. Yet she received no credit for this cultural transformation.

Personal Life and Family Dynamics

While Levina’s professional life was extraordinary, her personal life remains largely mysterious. Her marriage to George Teerlinc appears to have been successful by Tudor standards. He sometimes accompanied her on royal commissions, as when they were both sent to Princess Elizabeth in 1551 to “drawe out her picture.” This suggests a partnership where George supported his wife’s career, unusual when most men expected their wives to abandon professional pursuits.

Their son Marcus grew up in an unusual household where his mother was the primary breadwinner and his father played a supporting role. We don’t know what profession Marcus pursued, but he would have had opportunities unavailable to most merchant-class children. Growing up at court, even peripherally, provided connections and education that money couldn’t buy.

The family lived in Stepney, then a prosperous suburb of London favored by successful merchants and minor courtiers. Their household would have reflected Levina’s unique status: neither fully English nor foreign, neither aristocratic nor common, occupying a liminal space that matched Levina’s professional position.

Managing this complex identity required constant vigilance. Levina had to dress well enough to attend court but not so well as to seem presumptuous. She had to maintain a Flemish identity that justified her foreign techniques while becoming English enough to be trusted. She had to be visible enough to maintain her position but invisible enough not to threaten male artists.

The Workshop and Techniques

Levina’s workshop practices represented a fusion of Flemish and English traditions adapted to the constraints of her gender. The Flemish tradition emphasized careful preparation and meticulous technique. Vellum was prepared with pumice and chalk, creating a surface smooth as silk. Pigments were ground by hand with a muller and slab, mixed with gum arabic for transparency or white lead for opacity.

The actual painting required extraordinary precision. Working on surfaces sometimes no larger than a playing card, Levina created portraits with individual eyelashes visible, jewelry rendered in actual gold leaf, and fabrics that seemed to shimmer with real thread. She developed techniques for capturing the translucency of pearls, the flash of diamonds, the soft sheen of velvet.

Her color palette was revolutionary for English art. Where Holbein had favored bold, clear colors, Levina introduced subtle gradations and soft harmonies. She understood how colors changed at miniature scale, how a red that looked vibrant in a full-size painting would appear harsh in a miniature. Her backgrounds often featured atmospheric effects, soft blues and grays that made the subject seem to exist in real space rather than against a flat field.

The frames for these miniatures were often as elaborate as the paintings themselves. Made by goldsmiths, they might include enameled cases, jeweled covers, or mechanisms that allowed the portrait to be worn as a locket. Levina had to work closely with these craftsmen, ensuring her paintings fit perfectly into their settings. This required precise measurements and understanding of how the painting would be viewed: in candlelight, in daylight, held in the hand or worn on the chest.

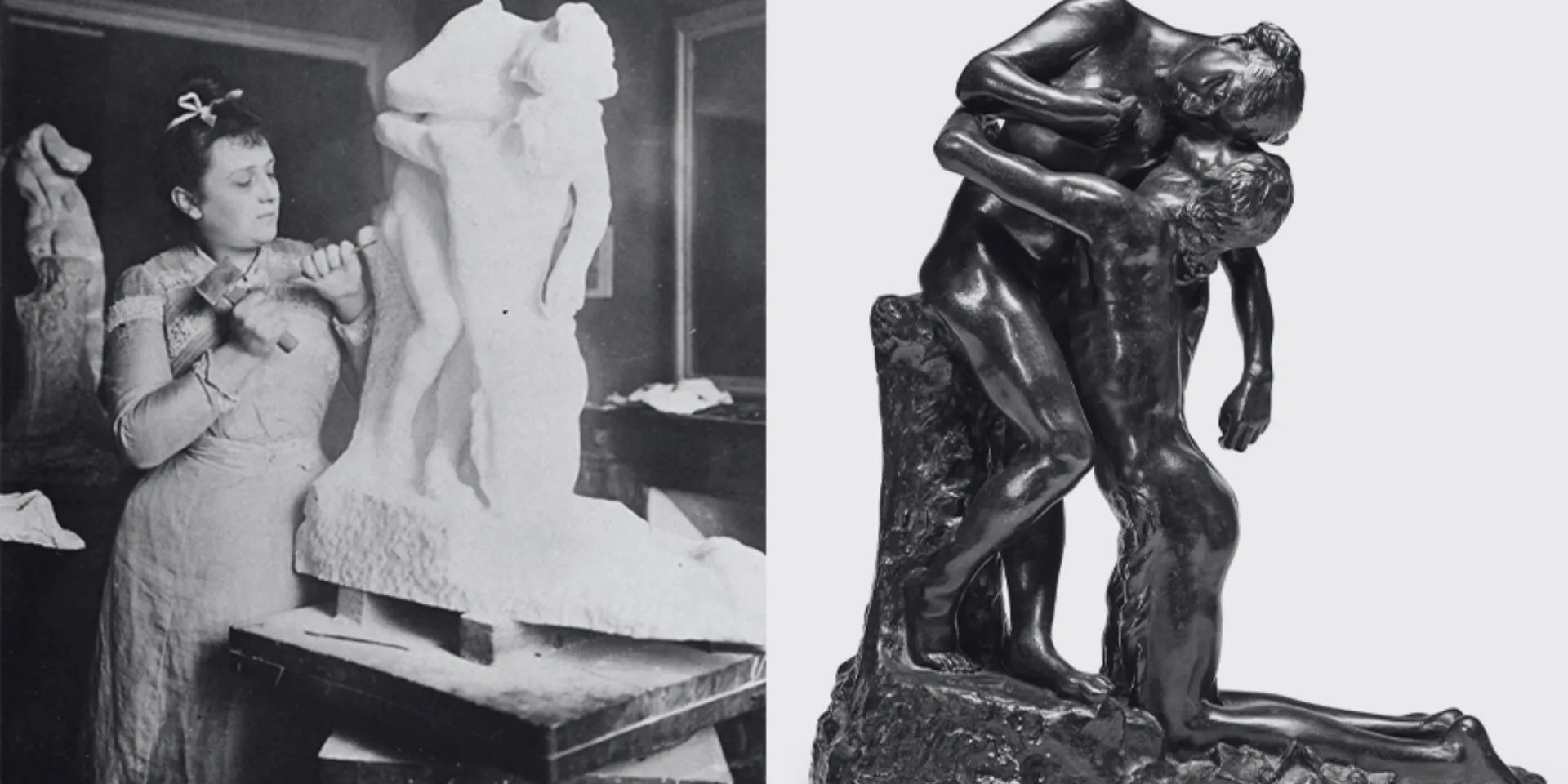

The Attribution

After Levina’s death in 1576, her artistic legacy faced systematic erasure. Paintings she created were attributed to her father, to Holbein, to Hilliard, to anonymous “followers” of male masters. This wasn’t accidental. Art historians and dealers had financial incentives to attribute works to famous male artists, whose paintings commanded higher prices.

The methods used to deny Levina credit reveal the deep biases of art history. When a high-quality miniature from her period was discovered, scholars would first try to attribute it to Holbein, even when the style clearly didn’t match. If that failed, they’d attribute it to Hilliard, even when the dates made this impossible. Only when all male candidates were exhausted would they grudgingly suggest “possibly Levina Teerlinc.”

Even when documentation proved Levina painted specific subjects, scholars found ways to deny her credit. Records show she painted Elizabeth I multiple times, yet when miniatures of Elizabeth from this period surface, they’re attributed to unknown male artists. The assumption was always that important portraits must have been painted by men.

This erasure had practical consequences beyond reputation. When museums and collectors believed a miniature was by Holbein, they paid premium prices and gave it prominent display. When the same miniature was reattributed to Levina, its value plummeted and it might be relegated to storage. The art market’s sexism became self-reinforcing: women’s work was worth less because it was by women, which proved women weren’t important artists.

Rediscovery and Reevaluation

Levina’s rehabilitation began in the early twentieth century when Caravaggio scholar Roberto Longhi started questioning attributions of Flemish-style miniatures to Italian artists. His work opened the door for reconsidering many anonymous works. But the real breakthrough came with the 1983 Victoria and Albert Museum exhibition, “Artists of the Tudor Court,” which attempted to establish a corpus of Levina’s work.

The exhibition curator, Roy Strong, faced enormous resistance. Established scholars who had built careers on certain attributions fought against changes. Dealers who owned “Holbeins” that might be Teerlincs had financial incentives to maintain old attributions. Even museum directors worried about the implications of reattributing works in their collections.

Despite resistance, the exhibition established that a significant body of work from the mid-sixteenth century showed consistent characteristics distinct from both Holbein and Hilliard. The brushwork was looser, the color palette softer, the psychological insight deeper. These works corresponded to documented commissions to Levina, appeared during her active period, and ceased after her death.

Modern technical analysis has supported these reattributions. X-ray fluorescence reveals pigment choices consistent with Flemish rather than German or English practices. Infrared reflectography shows underdrawing techniques taught in the Bening workshop. Computer analysis of brushwork patterns finds consistencies across disputed works that suggest a single hand.

Yet resistance continues. Major museums still hedge their attributions with “attributed to” or “possibly by” when discussing Levina’s work, while confidently attributing works to male artists based on far less evidence. The art market still values a “Holbein” at multiples of a “Teerlinc,” regardless of quality. The erasure that began with her death continues in subtler forms.

Political Accumen

Levina’s survival through four radically different reigns reveals extraordinary political intelligence. Each monarch brought not just different religious policies but entirely different concepts of monarchy itself. Henry VIII ruled as an absolute patriarch, Edward VI as a Protestant child-king controlled by regents, Mary I as a Catholic woman trying to restore old certainties, Elizabeth I as a Protestant woman creating entirely new forms of female power.

Levina adapted to each without compromising her essential work. For Henry, she painted power and virility even as his body decayed. For Edward, she painted divine authority in a child’s face. For Mary, she painted legitimacy and tradition. For Elizabeth, she painted timeless beauty and symbolic power. Each monarch got what they needed, rendered with skill that made criticism impossible.

Her New Year’s gifts to the monarchs show careful calculation. These weren’t just artworks but political statements. The Trinity she gave Mary was theologically safe. The portraits she gave Elizabeth emphasized the queen’s beauty and power. She never gave anything that could be interpreted as criticism or presumption. Every gift reinforced her position as valuable but unthreatening.

The fact that Elizabeth kept Levina for eighteen years, despite the queen’s notorious fickleness with servants, suggests exceptional diplomatic skills. Elizabeth dismissed ladies-in-waiting for marrying without permission, banished courtiers for perceived slights, and imprisoned nobles for suspected disloyalty. Yet Levina, foreign, Catholic, and female, maintained her position until death.

Technical Innovation

While Levina’s style was criticized by some as “weak,” modern analysis reveals sophisticated technical innovations. Her loose brushwork wasn’t incompetence but a deliberate technique that created effects impossible with tighter styles. By allowing colors to blend optically rather than mixing them on the palette, she achieved luminous skin tones that seemed to glow from within.

Her treatment of jewelry and clothing showed particular innovation. Rather than painting every detail, she suggested richness through strategic placement of gold leaf and carefully chosen highlights. A few dots of white could suggest pearls; a streak of gold could imply elaborate embroidery. This impressionistic approach was centuries ahead of its time.

She also innovated in composition. While Holbein typically placed subjects against plain backgrounds, Levina introduced atmospheric effects. Subtle gradations of color created depth, making tiny portraits feel spacious. She understood that miniatures weren’t just small paintings but a distinct art form requiring different approaches to create impact at intimate scale.

Her color harmonies were particularly sophisticated. She developed techniques for balancing warm and cool tones that created visual vibration, making static portraits seem alive. Her use of complementary colors, placed in small touches throughout a composition, created unity without monotony. These techniques influenced English miniature painting for generations.

The Gendered Economy of Art

Levina’s career illuminates the usually hidden gender economics of Renaissance art. Male artists could supplement court salaries with private commissions, teaching, and workshop production. They could train apprentices who paid for instruction, employ journeymen who produced saleable work, and establish dynasties that continued generating income after death.

Levina had none of these options. She couldn’t take private commissions without royal permission, which was rarely granted. She couldn’t openly teach students, as this would require admitting men to her private space. She couldn’t employ journeymen, as no male artist would work under a woman. Her knowledge and skills died with her, unable to be transmitted through normal professional channels.

This economic isolation meant court salary was her only significant income. While forty pounds annually was generous, it had to cover all expenses without supplementation. Male court artists who received less could still earn more through additional revenue streams. Levina’s higher salary was recognition of this reality, not favoritism.

The prohibition on teaching had cultural consequences beyond economics. Male artists created schools, styles that persisted through generations of students. Levina’s innovations disappeared with her death, only to be rediscovered centuries later. The development of English art was impoverished by the inability to transmit her knowledge through normal pedagogical channels.

Legacy and Influence

Despite systematic erasure, Levina’s influence on English art was profound. She established miniature painting as a distinctly English art form, introduced Flemish techniques that became naturalized as English, and created visual languages for female power that Elizabeth I used throughout her reign.

Her portraits of Elizabeth became templates for the queen’s image. The symbols Levina introduced, the poses she established, the idealization she pioneered, all became standard elements of Elizabethan royal portraiture. When later artists painted Elizabeth, they consciously or unconsciously followed patterns Levina established.

More broadly, she proved that women could excel in the most demanding artistic fields. In an era when women were excluded from most professions, she demonstrated that gender was no barrier to artistic excellence. Her success, even if uncredited, created precedents that later women artists could invoke.

Her technical innovations, particularly her atmospheric effects and psychological insight, influenced English portraiture for generations. The soft modeling and emotional depth that characterized the best English miniatures descended from her innovations, even when the artists themselves didn’t know their debt to her.

The Lost Works

The scale of Levina’s lost work is staggering. Documentation suggests she produced multiple portraits annually for thirty years, yet fewer than two dozen works are even tentatively attributed to her. Where did hundreds of miniatures go?

Some were undoubtedly lost in fires, particularly the devastating Whitehall Palace fire of 1698 that destroyed much of the royal collection. Others were probably destroyed during the English Civil War, when royal portraits became politically dangerous to own. But most were likely reattributed to male artists or classified as anonymous, their true creator erased.

The loss extends beyond individual works to entire categories of production. Levina designed seals, painted illuminated manuscripts, and possibly created large-scale portraits. None of these survive with certain attribution. We have documents describing works that sound extraordinary: full-length portraits of Elizabeth, group scenes with multiple figures, symbolic paintings of complex political allegories. All lost or misattributed.

Each lost work represents not just missing art but missing evidence of women’s capabilities. When people claim women produced little significant art historically, they’re often looking at a record from which women’s work has been systematically removed. Levina’s lost works are part of this larger erasure, this historical vandalism that obscured women’s contributions.

The Revolutionary Hidden in Plain Sight

Levina Teerlinc was a revolutionary who disguised herself as a servant. She infiltrated the most powerful court in Europe, shaped how power was visualized, and created art that influenced English culture for centuries. She did this while navigating religious upheaval, political chaos, and gender restrictions that should have made her career impossible.

Her story reveals the hidden infrastructure of women’s achievement. Behind the famous male artists were women grinding pigments, preparing canvases, managing workshops. Behind the celebrated male teachers were women transmitting knowledge through unofficial channels. Behind the canonical male masterpieces were women’s innovations, reattributed and erased.

Levina’s forty pounds annual salary made her one of the highest-paid women in Tudor England. But her true payment was the privilege of creating images that shaped history. Every portrait she painted was a political document, every miniature a node in networks of power. She painted the faces that launched armadas, sealed alliances, and started wars.

Today, when we see portraits of the Tudor court, we’re often looking at Levina’s vision whether we know it or not. Her psychological insight, her technical innovations, her symbolic language, all became so embedded in English visual culture that they seem natural, inevitable. This is her greatest triumph and greatest erasure: she succeeded so completely that her innovations became invisible.

Recognizing Levina isn’t just about correcting historical records. It’s about understanding how genius persists despite suppression, how innovation happens outside official channels, how excluded people find ways to contribute despite exclusion. Her paintbrush was a tool of infiltration, her miniatures weapons of subtle revolution.

In the end, Levina Teerlinc painted survival itself. In each portrait, she encoded strategies for existing in hostile spaces, for maintaining dignity under scrutiny, for exercising power without authority. She painted women and men who, like her, had to perform roles that didn’t quite fit, who had to project images that weren’t quite true. She was the artist of the precarious, the painter of those who couldn’t afford to be fully seen.

Her legacy isn’t just in the miniatures that survive or even in the techniques she pioneered. It’s in the proof she provided that talent transcends gender, that innovation happens in constraint, that the excluded will find ways to contribute. She painted a door in the wall of patriarchy, tiny as a miniature, through which centuries of women artists would follow.