Contents

ToggleA Union soldier lay dying in a makeshift Confederate hospital, his leg shattered by grapeshot, infection spreading like wildfire through his body. The Confederate surgeons had already moved on to other patients they deemed more likely to survive. That’s when she appeared—a small figure in men’s trousers and a modified Union uniform, her hair cropped short, a surgical kit in her hand. The Confederate guards tried to stop her, but she pushed past them. For the next three hours, she operated on that soldier and four others the Confederate doctors had abandoned. When Confederate officers finally arrested her as a spy, she didn’t resist. She’d already saved five lives that morning.

This was just another Tuesday for Dr. Mary Edwards Walker in April 1864. And this is the story they didn’t want you to know.

The Making of a Revolutionary

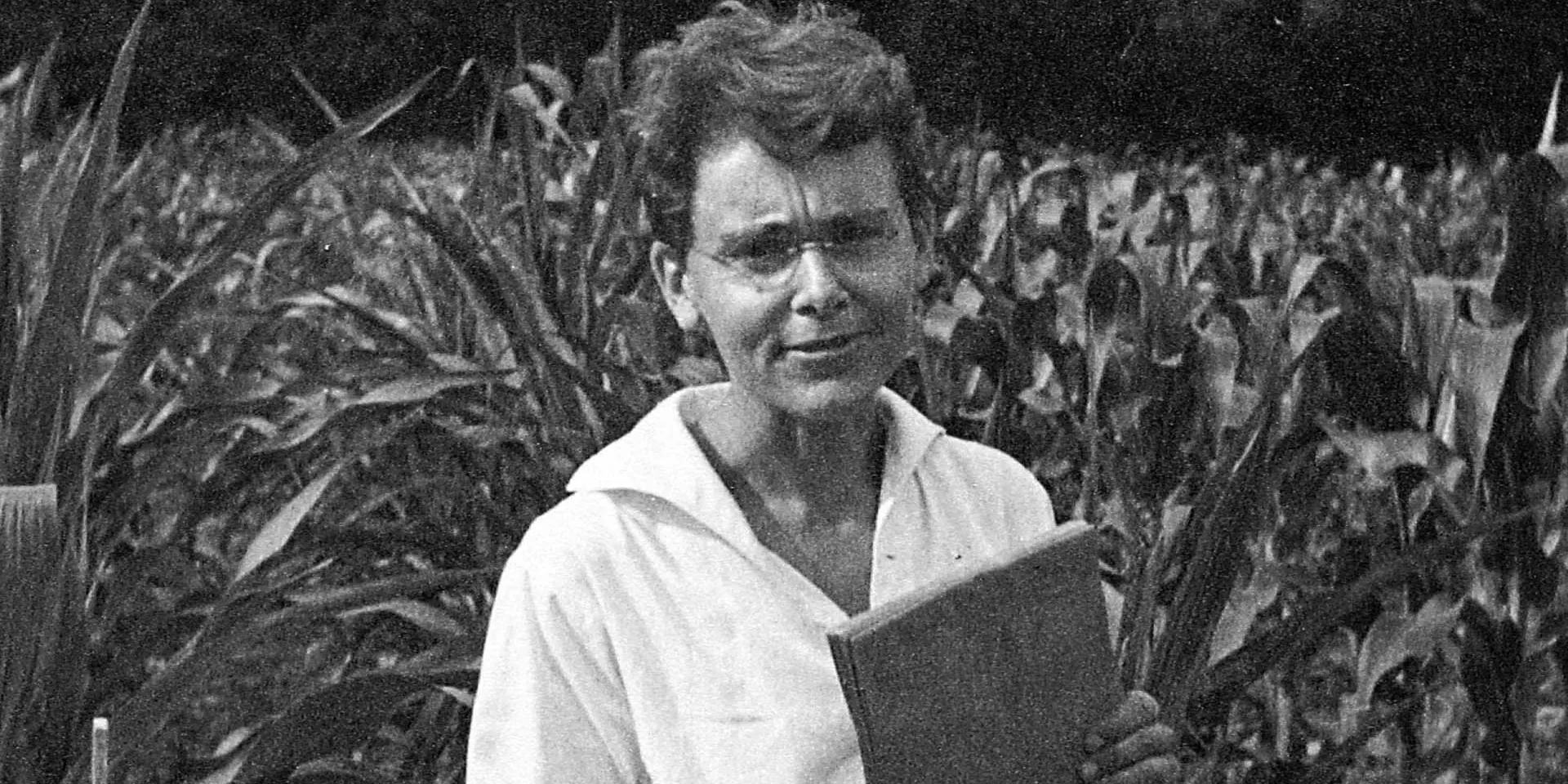

Mary Edwards Walker entered the world on November 26, 1832, in Oswego, New York, born to parents who would today be called radical progressives but were then considered dangerous freethinkers. Her father Alvah and mother Vesta Walker didn’t just talk about equality—they lived it. While neighboring farms operated on strict gender roles, the Walker household turned convention upside down. Alvah cooked and cleaned alongside his wife. Vesta worked the fields alongside her husband. Their five daughters learned carpentry and mathematics. Their son learned to sew and cook.

The Walkers founded the first free school in Oswego because they refused to accept that their daughters deserved less education than their son. Think about that for a moment—in the 1830s, when most Americans believed educating women would damage their reproductive organs and make them unsuitable for motherhood, the Walkers were building a school specifically to ensure their daughters received the same rigorous education as boys.

Mary grew up believing her mother’s radical teachings about health and clothing. Vesta Walker had nearly died from complications caused by tight corset lacing as a young woman, and she forbade her daughters from wearing these torturous devices that literally rearranged women’s internal organs. When Mary worked the farm, she wore trousers. When she studied, she wore comfortable clothing that allowed her to breathe. The neighbors called it scandalous. The Walkers called it common sense.

Medical School Against All Odds

At sixteen, Mary taught at the local school to earn money for her real dream: becoming a doctor. Not a nurse—a doctor. In 1850s America, this was like announcing you planned to become President. Women weren’t supposed to touch dead bodies (it would corrupt their delicate sensibilities), examine naked patients (even thinking about anatomy was considered obscene for ladies), or make life-and-death decisions (their emotional nature made them unsuitable for such grave responsibilities).

Syracuse Medical College accepted her application in 1853, making her the only woman in her class. Her male classmates treated her presence as either a joke or an insult to their profession. Professors routinely skipped over her during discussions. During anatomy lessons, she was often forced to wait until male students finished their examinations before she could approach the cadavers. One professor suggested she sit behind a screen during lectures about reproductive anatomy to protect her modesty. Mary refused. She graduated with honors in 1855, the only woman in her class to receive a medical degree.

Her wedding to fellow medical student Albert Miller that same year should have been a fairy tale ending. Instead, it was a radical political statement. Mary wore a dress that ended at her knees with trousers underneath—scandalous enough to make the local newspapers. She kept her own name—virtually unheard of in 1855. She removed the word “obey” from her wedding vows, causing the minister to nearly refuse to perform the ceremony. The marriage was doomed from the start, not because of Mary’s radical choices, but because Albert couldn’t keep his hands off other women.

The War That Changed Everything

When the Civil War erupted in 1861, Mary saw opportunity where others saw tragedy. She immediately volunteered as a surgeon for the Union Army. The Army’s response? They offered her work as a nurse. Mary refused. She would be a surgeon or nothing.

So she became a surgeon anyway, just without the Army’s permission or pay.

She appeared at the First Battle of Bull Run with her surgical kit, operating on wounded soldiers as bullets whistled overhead. When Army surgeons ordered her to leave, she ignored them. When they threatened her with arrest, she kept operating. What were they going to do—stop her from saving Union soldiers’ lives in the middle of a battle?

For two years, Mary worked as an unpaid volunteer surgeon, following the Army of the Cumberland from battlefield to battlefield. She slept in tents, waded through mud, and operated by candlelight in barns that served as field hospitals. She treated soldiers with gangrene, performed amputations without proper equipment, and extracted bullets while artillery shells exploded nearby. All without pay. All without official recognition. All while wearing men’s clothing because try performing surgery in a hoop skirt covered in battlefield mud.

Behind Enemy Lines

By September 1863, even the U.S. Army couldn’t ignore Mary’s competence any longer. They hired her as a “Contract Acting Assistant Surgeon”—the first woman ever given such a position. They assigned her to the 52nd Ohio Infantry, where she did something that would have been unthinkable for male Army surgeons: she regularly crossed enemy lines to treat Confederate civilians.

This wasn’t some humanitarian gesture blessed by both sides. This was Mary walking alone into hostile Confederate territory where Union surgeons had been shot on sight. She treated Southern women dying in childbirth, Confederate children with typhoid fever, and elderly civilians caught in the crossfire. She did this knowing that every trip could be her last.

On April 10, 1864, her luck ran out. After helping a Confederate surgeon perform an amputation on a Southern soldier, Confederate forces arrested her as a spy. The charges weren’t entirely fabricated—Mary had been gathering intelligence on Confederate troop movements during her medical missions. But she maintained she was simply a doctor treating patients.

They sent her to Castle Thunder, Richmond’s most notorious military prison. For four months, she endured conditions that killed dozens of Union officers. The food was rotten. The water was contaminated. Rats outnumbered prisoners. Disease ran rampant. Male prisoners at least received basic clothing. Mary, the only female military prisoner, was given a filthy dress and told to “dress like a proper woman.” She refused, wearing her tattered uniform until it literally fell apart.

The Confederates offered to release her if she agreed to stop practicing medicine and return North as a “proper lady.” Mary responded by treating sick Confederate prisoners using medical supplies she convinced guards to smuggle in. By the time she was exchanged for a Confederate surgeon in August 1864, she had lost 40 pounds and developed an eye condition that would plague her for the rest of her life. She returned to the Union lines and immediately returned to surgery.

The Medal They Tried to Steal

After the war ended, President Andrew Johnson faced a problem. Mary Walker had served with distinction, saved hundreds of lives, and endured imprisonment that permanently damaged her health. She deserved recognition. But she was a woman, and women couldn’t receive military commissions or medals.

Johnson found a loophole. At the time, the Medal of Honor’s eligibility rules did not explicitly require combat service or restrict the award to men. The original 1862 law creating the Army Medal of Honor stated it could be awarded to “such noncommissioned officers and privates as shall most distinguish themselves by their gallantry in action, and other soldier-like qualities.” A separate provision for the Navy’s version used similarly broad wording.

Mary Edwards Walker, though a contract surgeon and not a commissioned Army officer, technically held the status of a civilian employee attached to the Army during the Civil War. Johnson used the “other soldier-like qualities” clause and the lack of a gender restriction to justify awarding her the medal for her service — including crossing enemy lines to treat civilians and soldiers, enduring capture as a prisoner of war, and continuing work despite injury.

In short: the loophole was that the statute then in force did not mandate military enlistment or male gender, and the language was broad enough for Johnson to argue her actions met the “gallantry” and “soldier-like qualities” standard.

On November 11, 1865, he personally signed an executive order awarding Mary the Medal of Honor. The citation praised her “valuable service,” “patriotic zeal,” and the “hardships” she endured as a prisoner of war. Mary became the only woman in American history to receive the Medal of Honor.

She wore that medal every single day for the rest of her life. When people told her it was ostentatious, she pointed out that male recipients wore theirs to formal occasions without criticism. When critics said she didn’t deserve it because she never engaged in combat, she reminded them that she operated on soldiers while bullets flew past her head and Confederate artillery targeted her field hospitals.

Then, in 1917, the U.S. Army decided she didn’t meet the newly created standards to “sanitize the award and its stature.” They demanded she return the medal.

Mary’s response met the audacity in a befitting fashion: “You can have it over my dead body.”

She continued wearing the medal. When police arrested her for impersonating a military officer (yes, that actually happened), she fought the charges in court and won. When the Army threatened legal action, she dared them to prosecute a Civil War veteran who had suffered permanent disability in service to her country. They backed down.

The War That Never Ended

After the Civil War, Mary could have faded into quiet retirement, content with her groundbreaking service. Instead, she launched a second revolution—this time against society itself.

She opened a medical practice in Washington D.C., but patients were few. Who wanted to be treated by a woman doctor who dressed like a man? She supplemented her income by lecturing on women’s rights, health reform, and dress reform. Her standard lecture outfit—a man’s suit complete with top hat—guaranteed controversy and ticket sales.

Her position on women’s suffrage was so radical that even other suffragettes distanced themselves from her. While Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton argued that the Constitution should be amended to give women the vote, Mary argued that women already had the right to vote—the Constitution said “persons,” not “men,” and women were persons. The government, she insisted, was simply refusing to recognize existing rights.

In 1871, she attempted to register to vote in Washington D.C. When officials refused, she brought a lawsuit. She lost, but continued showing up at polling places every election for the next 48 years, demanding her constitutional right to vote.

HerWiki is built and maintained by the support of amazing readers like you. If this story inspired you, join the cause and help us make HerWiki bigger and better.

The Dress Reform Revolution

But Mary’s most visible battle was against women’s clothing itself. She had seen too many women die from complications caused by tight corsets. She had treated too many women who fainted from lack of oxygen due to restrictive clothing. She had watched too many female nurses during the war struggle to help wounded soldiers while wearing hooped skirts that caught on everything.

“The greatest sorrows from which women suffer today,” she wrote in 1871, “are those physical, moral, and mental ones that are caused by their unhygienic manner of dressing!”

She didn’t just write about dress reform—she lived it. Every day, she walked the streets of Washington in her modified costume: trousers under a knee-length dress, or later, a full man’s suit. She was arrested repeatedly for “impersonating a man.” Each arrest became a platform for her message: clothing should be practical, healthy, and chosen by the wearer, not dictated by society.

Once, in New Orleans in 1870, a police officer twisted her arm while arresting her and sneered, “Have you ever been with a man?” Mary replied, “Yes, I’ve been married. Have you ever been with a woman?” The officer had no response. When she appeared in court, the judge recognized her as Dr. Mary Walker, Civil War surgeon and Medal of Honor recipient. Case dismissed.

The Systematic Erasure

Mary’s medical contributions during the war were extraordinary. She pioneered sanitation techniques that wouldn’t become standard for another decade. She advocated for treating Confederate prisoners humanely when others wanted them left to die. She performed surgeries that male doctors considered impossible, including successful amputations in field conditions that would have challenged surgeons in proper hospitals.

Yet within years of the war’s end, official history began erasing her contributions. Battle reports that originally mentioned “Dr. Walker” were revised to reference “medical personnel.” Memoirs by soldiers whose lives she saved were edited to remove her name. When the Army Medical Museum created its Civil War exhibit, they included surgical tools used by dozens of male surgeons but excluded Mary’s equipment, which she had personally donated.

The suffrage movement, which should have championed her, instead distanced themselves from her. Her insistence on wearing men’s clothing made her “too radical.” Her refusal to compromise made her “difficult.” Susan B. Anthony privately wrote that Mary was “hurting the cause” by being so visible in her men’s attire. The movement that claimed to fight for women’s rights abandoned one of its most dedicated warriors because she refused to wear a dress while fighting.

The Woman Who Wouldn’t Break

In 1917, when the Army revoked her Medal of Honor, Mary was 85 years old, nearly blind, and living on a pension of $20 per month. She could have quietly accepted the decision. Instead, she fought with the same ferocity she had shown on Civil War battlefields.

She wrote letters to Congress, the President, and every newspaper that would publish her. She appeared at veterans’ events wearing her medal, daring anyone to try to remove it. When a young soldier once asked why she still wore a medal that had been revoked, she replied, “Young man, I earned this medal with my blood and my freedom. No board of men who never served a day in battle can take away what I earned.”

She was right. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter posthumously restored her Medal of Honor, acknowledging what Mary had always known—that she had earned it through service and sacrifice that transcended any bureaucratic review board’s narrow definitions.

The Death They Couldn’t Silence

Mary died on February 21, 1919, at age 86, just one year before the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote—the right she had insisted they always possessed. She died in the same house where she had been born, having come full circle but having changed the world in her orbit.

True to form, she was buried in a man’s suit with her Medal of Honor pinned to her chest. The local newspaper’s obituary called her “eccentric.” They dedicated more space to her clothing choices than to her medical achievements or her pioneering role in women’s rights.

The Revolutionary They Couldn’t Erase

History tried to forget Mary Edwards Walker. They removed her from medical texts that documented Civil War surgery innovations. They excluded her from suffrage histories because she didn’t fit their narrative. They dismissed her as a curiosity, a footnote, an aberration.

But Mary Edwards Walker was not an aberration. She was a revolution.

Every female doctor today stands on her shoulders. Every woman who wears pants to work continues her fight. Every female soldier who serves in combat zones follows in her footsteps. Every woman who keeps her name after marriage echoes her defiance.

Mary didn’t just break barriers—she obliterated them. She didn’t request permission—she took what was rightfully hers. She didn’t ask society to change—she changed it through sheer force of will.

When she crossed enemy lines to treat Confederate civilians, she demonstrated that healing transcends politics. When she refused to return her Medal of Honor, she proved that honor earned cannot be administratively revoked. When she wore men’s clothing despite repeated arrests, she established that personal freedom matters more than social conformity.

The medical establishment that refused to acknowledge her contributions? They eventually adopted every surgical innovation she pioneered. The suffrage movement that rejected her? They ultimately embraced every principle she fought for. The Army that tried to erase her? They now celebrate her as a pioneer who paved the way for women in military service.

Mary Edwards Walker spent her entire life being told “no.” No, women can’t be doctors. No, women can’t be surgeons. No, women can’t serve in war zones. No, women can’t wear pants. No, women can’t vote. No, women can’t receive military honors.

She responded to every “no” the same way—by doing it anyway.

This is why they tried so hard to erase her. Not because she was eccentric or difficult or radical. They tried to erase her because she proved that every barrier they put in front of women was artificial, arbitrary, and ultimately powerless against determination.

Mary Edwards Walker didn’t wait for permission to be revolutionary. She simply was. And in being herself—uncompromisingly, unapologetically, and unforgettably—she carved a path through history that no amount of revision could ever fully close.

She remains the only woman ever awarded the Medal of Honor. But more than that, she remains proof that one woman refusing to accept society’s limitations can change the world. They tried to bury her story, but Mary Edwards Walker was never one to stay down.

Over a century after her death, her message rings clearer than ever: Don’t ask for your rights. Snatch’em.